10/10 FILMS FOR ALL TIME

Subject to the inevitable variables of opinion over time, these are currently my most secure choices for a definitive personal top ten movie list of all time.

It pains me to have omitted 'The Apartment' (I could have made a top ten list from Billy Wilder films alone), 'Chinatown', 'Apocalypse Now', 'The Treasure Of Sierra Madre' and 'Groundhog Day' off this list but I'm choosing films with a fairly specific focus.

My criteria is based firstly on atmosphere; secondly, memory (specifically where they fit into my own personal timeline) and thirdly, thematic/emotional sensibility.

1. Rebecca (1940)

Mrs. De Winter: Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.

I can remember vividly the first time I watched Hitchcock's 'Rebecca'. It was on Channel 4 the night before I started secondary school and it so greatly enthralled me with its ghostly/seaside tale that I forgot any nerves about starting Year 7 the following morning.

From that moment on, I always made sure to pay attention whenever a Hitchcock film came on television. I still maintain that of all his films, 'Rebecca' is the one that made the biggest impression on me, especially in terms of its cinematic atmosphere. Hearing Joan Fontaine's cut glass opening voice over as the camera slow tracks along a overgrown path through the grand iron gates of a ghostly looking Manderlay is perfectly dreamlike and exquisitely captures the pervading sense of the supernatural throughout the rest of the movie.

Laurence Olivier was never better on screen than as Maxim DeWinter and plays him with just the right amount of charm, neurosis and distracted impatience that the role requires.

Like my second choice on this list, 'Rebecca' is a film about the ocean and although studio bound, it conveys the sea spray and elemental importance of nature throughout the story which is essential to its sense of mystery. Considering the estate grounds were filmed in the Del Monte region of California close to Monterey and the beach exteriors used were of Catalina Island, off the coast of Los Angeles it seems impressive to me how the film manages so well to capture Cornwall, England in some magical and strange way.

Franz Waxman's score perfectly mirrors the nervous tension of the narrative as it winds like that sinister moonlit path to Manderlay to its fire ravaged climax.

To me, great films are like dreams you can actually remember, so much so that they live inside your memory forever.

Hitchcock's 'Rebecca' is one such dream.

2. Jaws (1975)

Though this was the film that resulted in many people becoming fearful of going for a swim in the sea, I found 'Jaws' more seemed to fetishise the attraction of the beach, the ocean and boats to a point that even the alluring attraction of those things resulting in death by shark attack would not deter me from enjoying them. I'm weird like that, although I did flinch last summer when a jelly fish bobbed alongside me whilst swimming in the Atlantic.

This movie is so purely elemental, even in the more domesticated scenes of Chief Brody's family home in the quaint seaside town of Amity, that you can almost smell the briny salt air through each frame of film. Quite a feat, if you ask me but absolutely the bare minimum for what Spielberg had to achieve with this film adaptation of Peter Benchley's monstrously successful book.

Luckily for us viewers, he achieves so much more than that on top.

What I especially love is that the film is split into two distinct halves - the first on land, the second at sea so in this way you're actually getting two films for the price of one. As the Great White predator picks off his prey victim by victim for the first half of the story, the tables are turned when Quint, Brody and Hooper all go after the 25ft monster out at sea throughout the second half.

And not merely content with simply being the most perfect popcorn munching summer blockbuster of all time, 'Jaws' somehow also manages to be a masterpiece of atmosphere and tension that has enough narrative depth to draw comparison with Melville's Moby Dick thanks to the extra heft brought to the screenplay by that madman John Milius who always reminds me of Walter Sobchak (John Goodman) in the Coen Brothers 'The Big Lebowski'.

For who can ever forget Quint's iconic monologue when he recounts his experience on the USS Indianaopolis.

Quint: Y'know, by the end of that first dawn... lost a hundred men. I dunno how many sharks. Maybe a thousand. I dunno how many men, they averaged six an hour. On Thursday mornin', Chief, I bumped into a friend of mine, Herbie Robinson from Cleveland- baseball player, boatswain's mate. I thought he was asleep, reached over to wake him up... bobbed up and down in the water just like a kinda top. Upended. Well... he'd been bitten in half below the waist. Noon the fifth day, Mr. Hooper, a Lockheed Ventura saw us, he swung in low and he saw us. Young pilot, a lot younger than Mr. Hooper. Anyway, he saw us and come in low and three hours later, a big fat PBY comes down and start to pick us up. Y'know, that was the time I was most frightened, waitin' for my turn. I'll never put on a life jacket again. So, eleven hundred men went into the water, three hundred sixteen men come out, and the sharks took the rest, June the 29th, 1945.

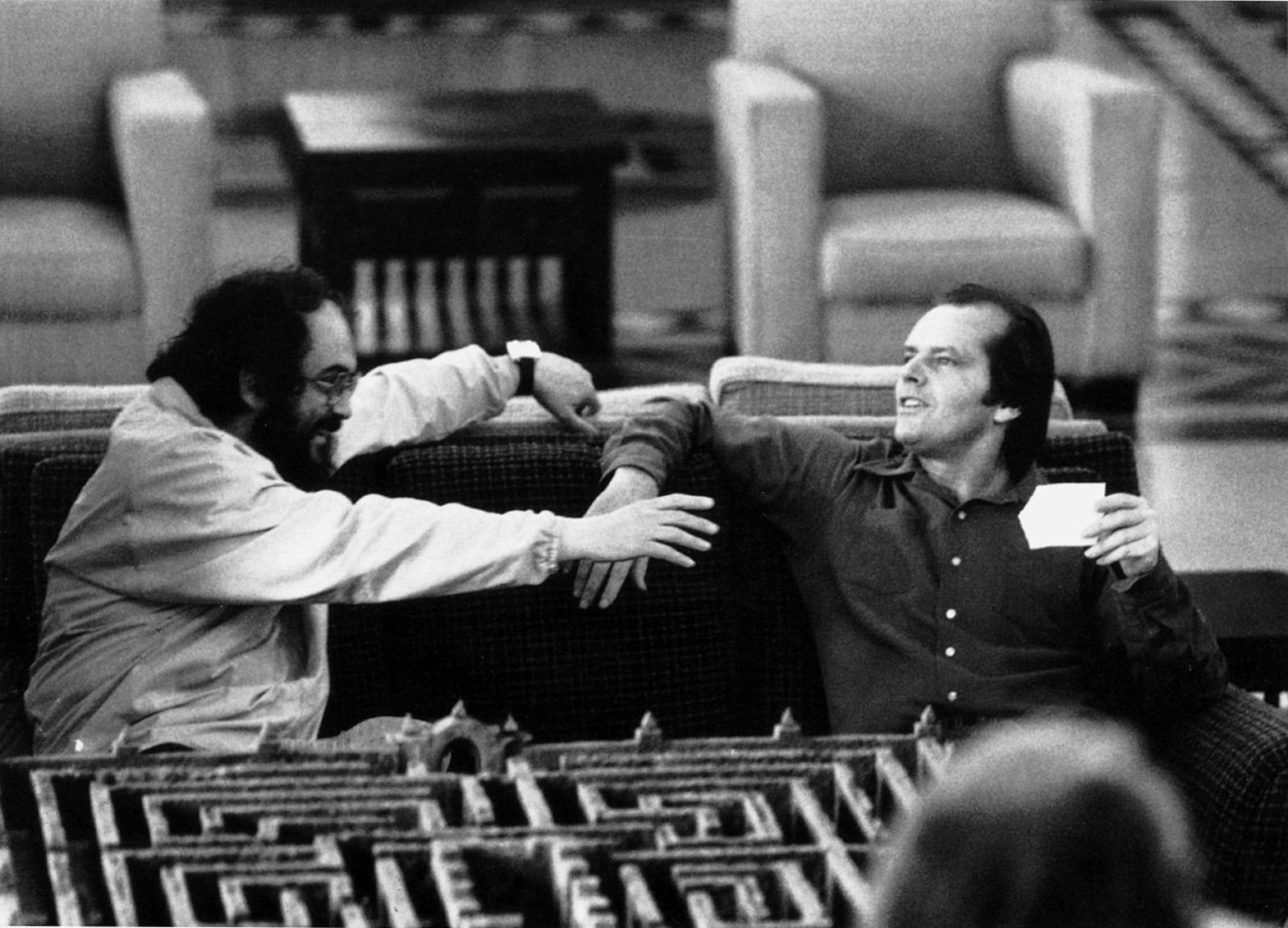

3. The Shining (1980)

Grady Twins: Hello, Danny. Come and play with us. Come and play with us, Danny. Forever... and ever... and ever.

This isn't even my favourite Kubrick film. '2001 : A Space Odyssey', 'A Clockwork Orange', 'Barry Lyndon' and 'Eyes Wide Shut' would probably rank above 'The Shining' overall but I cannot deny that I am forever hypnotised by this one more than all the others if for no other reason than the way the camera moves in each frame. The film feels organically alive with barely any stasis throughout its 2hrs 26 min running time. It's as if the camera presence in itself is the greatest character of the movie as it stalks the Colorado mountains, the huge rooms on the ground floor of the hotel (especially the Indian room) and those endless carpeted corridors of the floors above that resemble the mazy labyrinth of tall hedges outside in the grounds of the Overlook.

'The Shining' was also symbolically for me one the best lockdown movies during Covid when most of the globe began to shut down and resemble one mass Overlook Hotel as we were all reduced to being either Jack Torrance, Wendy or Danny inside our own pandemic nightmare, prepping our cupboards with tins of food, wondering when the invisible threat might strike us in our isolated shelters and trying to ignore the Tony-like voice in our paranoid minds (just kidding!). Of course, some saw government-enforced lockdowns as a wonderful thing and enjoyed their time living in their covid bubbles as if it was their own personal Wes Anderson movie - The Grand Bubonic Hotel or something to that effect.

Strangely though, as much as The Shining is described as a horror film/ghost story, I find it weirdly comforting in its overall pace, art direction and atmosphere. Not that I'm condoning blood filled elevators, massacred victims of frenzied axe attacks or fellating men in bear suits but the film overall has a mesmeric, slow pace that is unnerving and yet also strangely relaxing.

Perhaps Kubrick knew that by making a more seductively beautiful horror film it would appeal more widely to audiences beyond just the grubby horror enthusiasts or Stephen King nuts. In this sense I see The Shining more as an art film than anything else and the culminative effect is like experiencing a lucid cinematic dream turned nightmare.

One I can't help but return to.

Forever ... and ever ... and ever.

4. The Long Goodbye (1973)

Altman's The Long Goodbye is definitely the more shaggy, unkempt counterpart to Chinatown's slick Californian cinematic richness but it offers just as much in its evocation of a city that disguises dark secrets behind its pretty but superficial facade. One is set in the 30's, the other in the 70's but both have murder and water feature prominently in their stories whether it's in a garden pond, down an industrial sluice or in the raging sea itself.

That elemental dichotomy between the desert and the water and all the madness in between seems to set the tone for both films equally, although the use of water specifically in Chinatown is far more politically overt than The Long Goodbye which uses water in a more symbolic way, often to wash away the torment and sins of the characters.

For me, there's just something irresistible about the sonnambulistic Marlowe (Elliot Gould) wandering through the streets of 1970's Los Angeles, looking like an unmade bed. J.J Gittes (Jack Nicholson), on the other hand, is more dapper and purposeful in leading his enquires and yet both men find themselves led astray by their underlying well intentioned nature, especially by those who know how to manipulate them, namely women or femme fatales.

Spoiler alert. Although Marlowe resolves his case emotionally and psychologically on his own terms, Gittes is left with an open wound as what he uncovers is far more expansive politically in its broad criminal implications than the more intimate tale of The long Goodbye which is far more to do with loyalty, friendship and betrayal.

The fact that Leigh Brackett (screenwriter of Howard Hawk's 1946 classic movie "The Big Sleep") wrote this 1970's update of Chandler's novel adds yet another meta layer to The Long Goodbye's somewhat post-modern approach to reimagining Marlowe for a new generation of movie goers. Both she (Brackett) and Altman had the idea that this would be "Rip Van Marlowe" waking from a thirty year coma into the 1970's, an anachronism wandering between different incarnations of the city of Los Angeles. It totally works in my opinion and makes Marlowe seem like the last bastion of morality in a city that's decaying fast. His devotion to his cat seems positively chivalrous in this instance.

Another "character" that deserves a special mention in The Long Goodbye is the music. John Williams's score is ingenious, repeating the same title music over and over again but in different genres adjusted to the interiors/exteriors of the scenes throughout the story. Some of the many iterations of The Long Goodbye theme include it being played through a supermarket tannoy, by a Mexican Mariachi band and even a doorbell. It's quite a feat to pull off and the composer does it brilliantly, displaying his full compendium of genre styles to suit the repetition of his main theme.

5. Singin' In The Rain (1952)

For one whole year after I first saw it one Boxing Day afternoon as a teenager, I think I watched 'Singin In The Rain' more times than was healthy, perhaps more times than any movie I've ever watched when you tote them all up.

What was it that so bedazzled me outside of the insane craftsmanship, witty script, step perfect dance sequences and riotous use of technicolour to say nothing of the ingenious montages, flashbacks and the overall historical significance of the film's story charting the transition from the silent era to sound?

In a word ... heart.

This film may have made inhuman demands on its cast but it is the epitome of humanity in its overall execution and presentation, like a never ending christmas present that can be repeatedly opened and enjoyed every day for the rest of time.

And as for the iconic title number where Gene Kelly dances in a grey woollen suit whilst being drenched by all the rain they could muster in California during a water shortage in Culver City, could there ever be a more perfect definition of personal freedom for the human spirit than this iconic sequence? It's only when a skulking police officer arrives at the end of the scene as Kelly lifts his feet furtively out of a giant puddle, that we are given a cold, watery reminder of mortality in a moment of genuine transcendence.

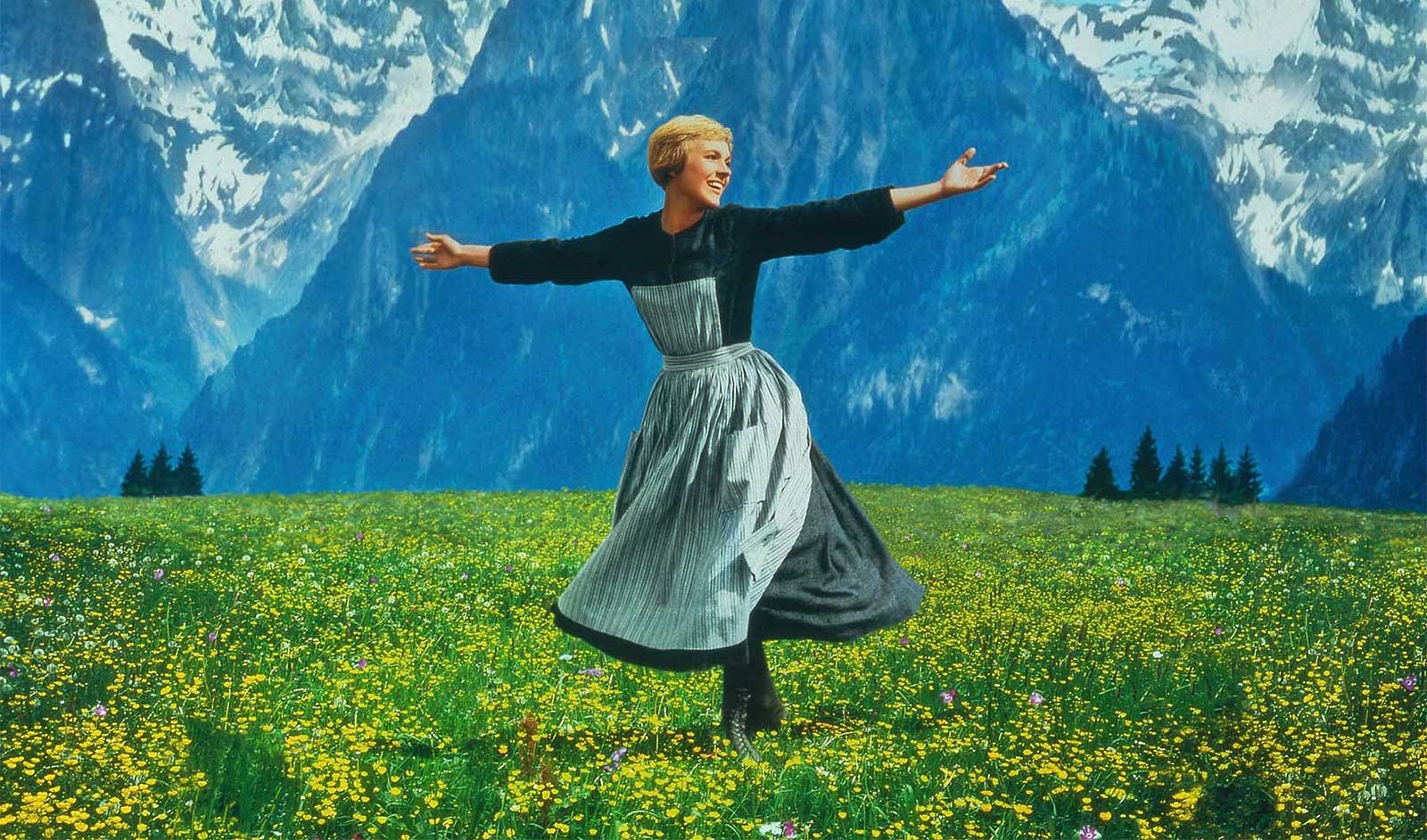

6. The Sound Of Music (1965)

Another musical I'm afraid. A co-screenwriter I used to work with once told me that a script consultant who had been brought in to help him with a project had said 'The Sound Of Music' was her favourite film of all time, partly due to its immaculately plotted story beats and how perfectly each one of them were paced and placed. I'd never really considered it that seriously until I heard that but ever since I've returned to it frequently and have realised that it is close to perfection in almost every aspect.

One scene in particular stands out to me as being among the best scenes in all of cinema: the one where stern Captain Von Trapp finally submits to the power of music and joins his children in song. It is perhaps the perfect scene to illustrate the very definition of what a musical should be - when words fail to express our feelings in a moment music is the next highest expression of what's in our hearts.

On top of that, there is an epic grandeur to the locations and scenery which opens up the film musical form in a way that had never previously been achieved. This gives the music its visual equivalence and justifies its being originally shot on 70mm.

Plus, similarly to 'Fiddler On The Roof', 'The Sound Of Music' deals with dark historical events and without necessarily delving too deeply into them, contrasts the more sugar sweet sentiments of some of the other parts of the movie which in turn provide a perfect balance.

I should also mention the effortlessly brilliant Rodgers and Hammerstein and their ability to tell simple, heartfelt stories with great sincerity and songs that burrow into your brain like insatiable ear worms.

7. A Room With A View (1986)

Mr. Emerson: I don't care what I see outside. My vision is within! Here is where the birds sing! Here is where the sky is blue!

If in a court of law, one had to prove that paradise was indeed on earth then you might present the jury with the iconic scene in 'A Room With A View' where Lucy Honeychurch and George Emerson finally kiss in a field of red poppies somewhere in the Florentine hills as a soprano singing 'Chi Il Bel Sogno Di Doretta' from Puccini's 'La Rondine' plays over the scene as Exhibit A.

And as an overall adaptation of a great book, you will rarely find a better example than Merchant and Ivory's 1986 movie version of E.M Forster's gentle romantic/comic novel set in Italy and England around the early 1900's.

When I was younger I mostly related to the impetuous George Emerson the most; now I find I relate more to his father who does a good line in earthy wisdom, a sort of more relaxed and genial Falstaff amongst a group of prim and proper types who mistake his honesty for eccentricity.

Though truth be told, I find almost all the characters in this story so loveable in their own way that they seem to me to reflect the best virtues of all humanity one way or another, even the pretentious Cecil Vyse (Daniel Day Lewis) who prefers the company of books to the company of his fiancée Miss Honeychurch.

But ultimately it is both Italy and England that are the greatest successes of this perfect film as both are shot as beautifully as any landscape painting by Sargent or Corot.

More and more I believe that films I return to repeatedly are essentially worlds I want to live in or travel to for an hour or two. I can think of few nicer places to return to than Forster's England, playing tennis with the Honeychurches and perhaps even going for a swim in the lake with Mr Beeb and the boys.

8. Eat Drink Man Woman (1994)

Eat Drink Man Woman is a happier version of King Lear but set in 1990s Taiwan with three daughters instead of sons. Ang Lee and screenwriter James Schamus fuse together all the best elements of the films of Yasujirō Ozu but with a slicker Hollywood gloss and yet manage to similarly mine the depths of the human condition just like Tokyo’s great director through their rich, multi-layered characters without compromise of a potential paradox.

The cast is perfection and the screenplay is an object lesson in crafting a multi-storyline structure without tiring the audience. And yet, even with all the profound staples of great storytelling included in this early And Lee masterpiece perhaps the greatest achievement of the film is in the director's exquisite filming of the preparing and cooking of delicious asian food, far better than any film before or since. Certainly, not even the foodie classic 'Tampopo' (1985) from Japan gets remotely close to inspiring appetites from visual hunger like Eat Drink which somehow sates the soul and the taste buds equally.

9. It's A Wonderful Life (1946)

I first watched 'It's A Wonderful Life' slap bang in the middle of summer on my friend's video projector as we worked our way through several old black and white classics in one evening.

Ignoring the obvious incongruity of enjoying a Christmas movie on a summer's night, I perhaps looked at Frank Capra's masterpiece more objectively as a drama than the festive favourite I'd heard people talk about, as familiar as chestnuts roasting on a winter's fire.

What we have here in this Dickens meets Norman Rockwell-like tale is the story of a man who, in the pits of his ultimate despair, feels he is worthless and desperately needs reminding of his value by those around him.

The last minute, roll of the dice heavenly reminder comes in the form of a portly guardian angel called Clarence who shows protagonist George Bailey glimpses of what the world would be like without him and it makes him appreciate that he has genuinely made very real and profound tangible differences in the lives of those he loves the most. It is a timeless tale that contains a very important message for every one of us who cares to take it in: that how even the smallest seeming lived of lives, like the proverbial butterfly's wings setting off a hurricane, can play a significant part in positively shaping the reality of the world around you.

10. Miller's Crossing

Geniuses they may be, but I fear the Coen Bros could spend the next one hundred years making movies and they'd never repeat the unique magic of what in my opinion is their greatest film, ‘Miller's Crossing’ (1990).

With a plot as perfectly designed as ‘Casablanca’, dialogue as snappy and witty as any from a Billy Wilder or Howard Hawks film, and with a wholly original visual aesthetic (greens, reds and dark browns) that brings a warmth to the gangster noir genre that I'd never seen before, ‘Miller's Crossing‘ simply has no apparent flaws to my mind.

To say nothing of that most human and heartfelt movie score by film composer Carter Burwell, who adapts the traditional Irish folk ballad 'Lament for Limerick' and turns it into something truly epic and unforgettable.

Tom Reagan : If I'd known we were gonna cast our feelings into words, I'd've memorized the Song of Solomon.

But when it comes down to it, the heart of the film for me has to be Gabriel Byrne's performance as Tom Reagan, a man who dreams of losing his hat, but ends up losing much more. A loyal consigliere to his gangster boss Leo (Albert Finney), the entire plot could be seen as a repressed love story between these two men who struggle to say they love each other, until it's too late. The entire fate of the town is turned upside down as a consequence of their mutual pig headedness and a violent civil war erupts around them, sparing few in its wake.

Tom Reagan : Think about what protecting Bernie gets us. Think about what offending Caspar loses us.

Leo : Oh, come on, Tommy. You know I don't like to think.

Tom Reagan : Yeah. Well, think about whether you should start.

Byrne as Tom manages to be enigmatic, funny, sly, vulnerable and an ice cold killer all at once, such are the many layers to his character, which is surely all credit to the Coen's amazing work on characterisation and overall screenplay brilliance which they have become deservedly world-reknowned for.

In some ways Tom reminds me of Bogart's Rick, only the stakes are more provincial in ‘Miller's Crossing’ than in ‘Casablanca’. The fascinating thing about both men, though, is that they try and conceal their emotions behind a tough facade, but deep down, we sense they hurt as much as the rest of us. Cynicism is the mask they both deploy to survive and stay in the game of life. Occasionally it slips and we soon realise they are more like us that we may have imagined from the initial scenes of wise cracks, bravado and whiskey.

Tom's concern for Leo is almost like that of a patriarch at times, at others more a loyal servant. He often appears to see his boss as a big kid who needs reigning in, unable to strategise or calulate the risk his enemies pose toward him and his fragile empire.

Leo is a feelings kind of a guy with an impetuosity that Tom resists. Between the two of them, they would make a perfect couple if it wasn't for the fact they're in love with the same woman, Verna (Marcia Gay Harden).

It just so happens that there are at least three variations of love triangles in this classic movie, which is yet again, further proof to me of the genius of the film's multi-layered plot. However, it's the central one that is most pivotal to the narrative bookends, that of Tom, Leo and Verna, which ironically is the only one that is ultimately resolved peacefully in the end.

Love triangles are hard to pull off in writing terms; one character always tends to invite more sympathy than the others, but in ‘Miller's Crossing’ the balance is perfectly judged and we understand all three parties involved and their motivations.

With Leo, loyalty is key, for Verna, it's security.

And for Tom, well, maybe he's just afraid of getting too close to anyone, for fear he might get hurt.

BONUS BALL (1) - Rear Window (1954)

Everyone needs a Saturday afternoon movie in their top 10 (12?) best film list and Alfred Hitchcock's 'Rear Window' is mine. Not only a Saturday movie mind but one of the best relationship movies ever. There aren't many films I can think of that capture the differences between men and women more accurately than in 'Rear Window', where the unlikely pairing of James Stewart and Grace Kelly actually proves that you don't always need such a cosmetically obvious or perfect pairing of leads when it comes to striking the right chemistry on screen.

And what an incredible feat it is to make such a cinematic film from essentially one fixed location. In the hands of lesser talents this could have been way too theatrical in its approach and would have felt positively claustrophobic to a fault with no room to breathe a bit like the central character itself. The genius of Hitchcock is that he can convey claustrophobia when he chooses to whilst letting the film expand and breathe in subtle ways. In some ways there is a perfect symbiosis between the role of the director in the making of this film and the predicament the injured main character finds himself in.

It's even more impressive when you compare it to another masterpiece that pays homage to 'Rear Window' but using in that instance just a few characters to focus on. Kieslowski's 'A Short Film About Love' is also one of my favourite movies but has far less spinning plates to deal with the story it tells. What Hitchcock and his screenwriter John Michael Hayes create is an entire symphony of portraits all observed from the wheelchair of L.B. Jeffries and they combine this with substantial characters and themes whilst never forgetting to entertain the audience with a good old fashioned murder mystery at the end of it.

BONUS BALL (2) - F For Fake (1973)

'F For Fake' is Orson Welles having the best fun ever with film, editing, his own unique camera trickery and sleights of hand together with his unique brand of whimsical philosophy combined in a deceptive assortment of archive footage he bought for cheap from the BBC.

It's Orson opening up his extensive toy box of tricks learnt over decades in film and performing an act of magic, one he pulls off perfectly as he investigates art forgery, the value of art through time and conspiracy theories.

And in perhaps the most profound moment of all of Welles's work, he muses on the insignificance of personal signature in the grand scheme of time.

Orson Welles: Our works in stone, in paint, in print, are spared, some of them, for a few decades or a millennium or two, but everything must finally fall in war, or wear away into the ultimate and universal ash - the triumphs, the frauds, the treasures and the fakes. A fact of life: we're going to die. "Be of good heart," cry the dead artists out of the living past. "Our songs will all be silenced, but what of it? Go on singing." Maybe a man's name doesn't matter all that much.

Hanging out with con men such as Elmyr De Hory and Clifford Irving on the island of Ibiza is my idea of a perfect groove. Having the added bonus of geniuses Howard Hughes and Orson himself thrown into the mix makes 'F for Fake' an undisputed masterpiece and one that rewards multiple viewings.

This film is truly inimitable, unlike those many art works that Elmyr is so brazenly and flippantly able to copy.