A PERFECT FOOL

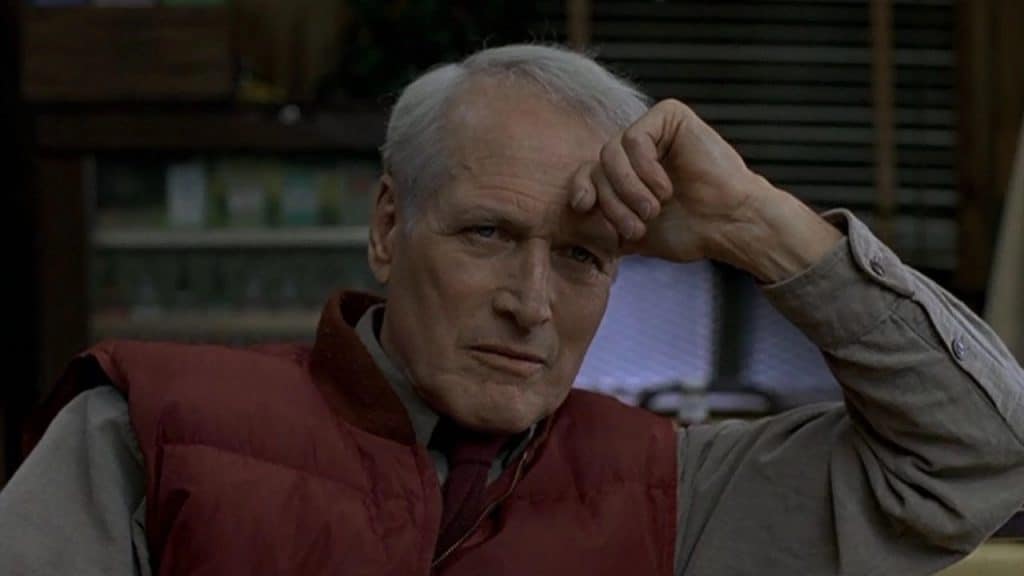

There's a glow and truth in Paul Newman's final leading film role that reminds me of a warm streetlight reflected on midnight snow. In Robert Benton's Nobody's Fool (1994), the veteran actor plays Sully, a man on the precipice between old age and very old age. He's not raging against the dying of the light, as Dylan Thomas would have it, but rather living in the present under the neon glow of his local bar, beer in hand, seemingly oblivious to the prospect of Father Time catching up to him—even as he slows down with a badly injured knee. After a reunion of repair with his son and dealing with several other developments in his personal life, born mostly from his own self-made crises, Sully does finally accept his aging fate with the grace of a stoic. Even then, however, we suspect old habits die hard.

Sully is in many ways a modern version of Hans Sachs, the master cobbler in Wagner's comic opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg: he must both honour his role and responsibilities in his community and, at the same time, let go of the possibility of recapturing his youth by loving someone younger. In Sachs’s case, this is Eva Pogner; in Sully’s, it is Toby Roebuck (played by Melanie Griffith).

Newman's Sully is truly one of the most accomplished, all-around performances the legendary actor delivered in his long film career—full of range and endless details that could fill an entire treasure chest. I would certainly be hard-pressed to choose between this last great leading performance and his Oscar-winning turn in Martin Scorsese's The Color of Money (a personal favorite of mine) ten years earlier. But in Nobody's Fool, we get an extra degree of humanity that we do not see in pool shark Fast Eddie Felson, who is too emotionally contained as a hustler to break down the way Sully does at the film’s tenderest moments.

Nobody's Fool is a film for younger men to relate to older ones, and for those getting on in years to reconcile with aging in a way that seems to embrace the defiant unchangeability of their innate character—while still leaving room for the possibility of redemption, both in small victories and in the concessions that only humility born from painful experience brings to a hard-headed man like Sully, like light shining through the cracks of a dark house.

In the final scene, as Sully settles into his chair and his landlady and cohabitant (played by Jessica Tandy) makes him a cup of tea after a long day of “events,” we sense that he has finally freed himself from the existential anguish rooted in growing up with an abusive father—a trauma that has been haunting him and, perhaps, leading him to avoid facing reality with his own son and family.

Now he is resolved in who he is and, much like the newly acquired Doberman Pinscher resting at his feet, can sleep soundly, having accepted that he's finally found his home.