CAMELOT

“Don’t let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief, shining moment that was known as Camelot.”

I sometimes reflect on the paradox that, while the United States prides itself on being a republic, it has long been drawn to the pomp and circumstance associated with monarchy and to the notion of a symbolic “king” or “queen” who can safeguard the nation against its adversaries.

Perhaps the most famous example of this phenomenon was John F. Kennedy, whose time in the White House with his wife was frequently likened to the reign of King Arthur and Queen Guinevere in Camelot. This narrative entered the public consciousness only after Kennedy’s assassination, when Jacqueline Kennedy, in an interview with Life magazine, invoked the imagery of Camelot to define her husband’s presidency as a fleeting but luminous moment in American history.

“There will be great presidents again... but there will never be another Camelot.”

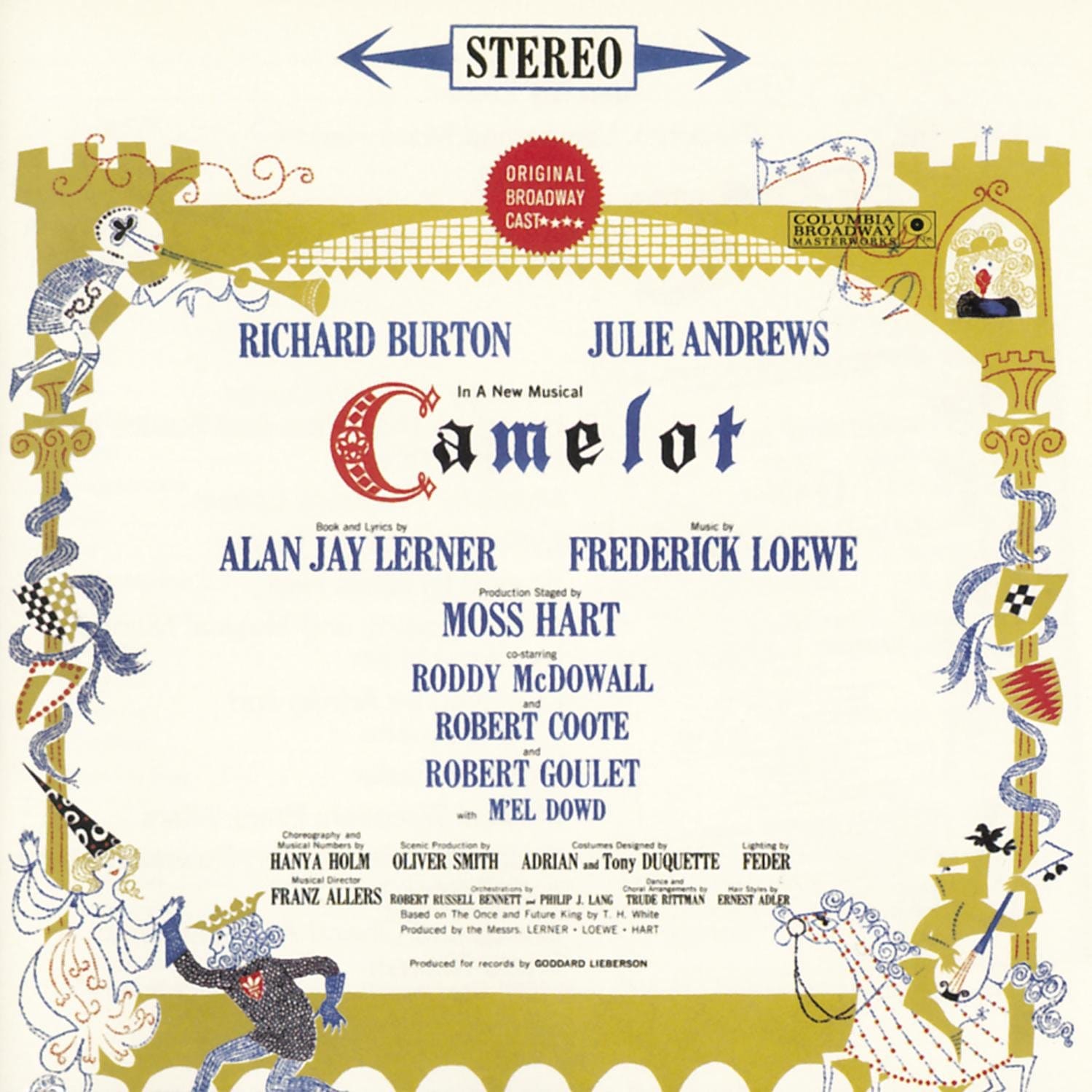

She also described how she and her husband would often play the Camelot Original Broadway Recording by Alan Jay Lerner and Arthur Loewe in their bedroom at night—a cosy, intimate image: a spinning record on a turntable, and the dream of a nation held in the heart of a man who was more like a prince than a king, yet who captured a royal zeitgeist of youth in high office that was unusual for such a position, as Kennedy was the youngest man ever elected president of the United States.

In many ways, the analogy of King Arthur's Camelot with JFK's White House finds its deepest resonance in the comparable tragedy of both their lives and reigns cut short. Arthur’s idealised vision was never fully realised, just as Kennedy’s vision for a vibrant, youthful America leading the way to a brighter future ended abruptly with his assassination. The fleeting nature of both “reigns” allows them to exist more vividly in the imagination than perhaps they ever could have in reality, immortalised not only by myth and legend but also by the cultural memory, filled with regret, of what might have been. In this sense, Camelot is less a literal place and more a symbol of possibility—an emblem of hope, ambition, and the fragility of human life and leadership.

Though America decisively rejected monarchy in 1776, the occasional yearning for a king or queen to save the country has continued to permeate the nation’s politics—like a phantom limb. And beyond nepotistic political dynasties such as the Bushes and the Clintons, who carry an air of entitlement in assuming high office, both Obama and Trump have been accused of exercising their executive authority with a “monarchical” air, while Hillary Clinton and Kamala Harris have been referred to (mostly in internet parlance) as 'queens'.

In this sense, it is perhaps pertinent to recall George Bernard Shaw’s observation: “Kings (and queens) are not born; they are made by artificial hallucination.”