DESTRUCTION AND CREATION

When Steve Judd (Joel McCrea) lies shot and wounded at the end of Sam Peckinpah's Ride the High Country, it's hard not to see it as the symbolic end of the American Western in its classic form at that juncture in cinema history. In 1962, Ride the High Country effectively served as the last rites for the cowboy as audiences had come to know him in the films of Ford, Hawks, and Mann. Yet even here, the grim reality beyond the familiar archetype begins to reveal itself in typical Peckinpah fashion, foreshadowing his revisionist approach to the Western genre in later work.

It makes perfect sense that Peckinpah would close the chapter on the old world to birth a new one seven years later, after spending much of the 1960s in television and relative cinematic doldrums (with Major Dundee being a notable misfire).

When he returned with The Wild Bunch in 1969, Peckinpah re-emerged on the big screen with a far more world-weary reassessment of the Old West and a new cinematic language of violence—one that eerily seemed to anticipate the Manson bloodbath on Cielo Drive that same year. The reality of violence had now become depressingly visceral, far removed from the more cartoonish, unreal depictions that preceded it.

There is also a tangible sense of mortality that haunts its central characters in a way rarely seen before in Westerns. The well-weathered Pike Bishop (played by William Holden) and Dutch Engstrom (Ernest Borgnine) seem like men running more from Father Time than from the law that pursues them. Perhaps it's no wonder, then, that these men would rather die in a blaze of bullets than face the prospect of growing old.

At this stage, the Wild West is no country for old cowboys.

The German composer Richard Wagner similarly closed the book on Romantic opera when he wrote Lohengrin (1848), before returning six years later with the revolutionary Das Rheingold (1854), the first part of his epic Der Ring des Nibelungen.

When Lohengrin (the Swan Knight) disappears from Antwerp, Brabant, to Montsalvat—the mythical castle of the Knights of the Holy Grail—at the end of Act III of the opera, it can also be seen as symbolic of the passing of an era in culture and music. When Wagner returns with the mysterious watery prelude to Das Rheingold, he brings with it an entirely new approach to music drama, one that upends everything that came before. Nothing in earlier opera remotely prepared audiences for the revolution of Rheingold, which—along with Tristan und Isolde—could be considered the beginning of modernism in music. With an emphasis on endless harmonic tension and through-composed seamlessness in his scores, Wagner created an entirely new language for music and drama. And as the old world of shimmering strings and Romantic longing was sent gliding away on the back of a swan into the mythic past, an alien world of Nibelung construction emerged, mirroring the rise of industrialisation in the 19th century. Still inspired by myth, Wagner fused an epic allegory of power that exists outside of time while simultaneously commenting on the era in which he lived.

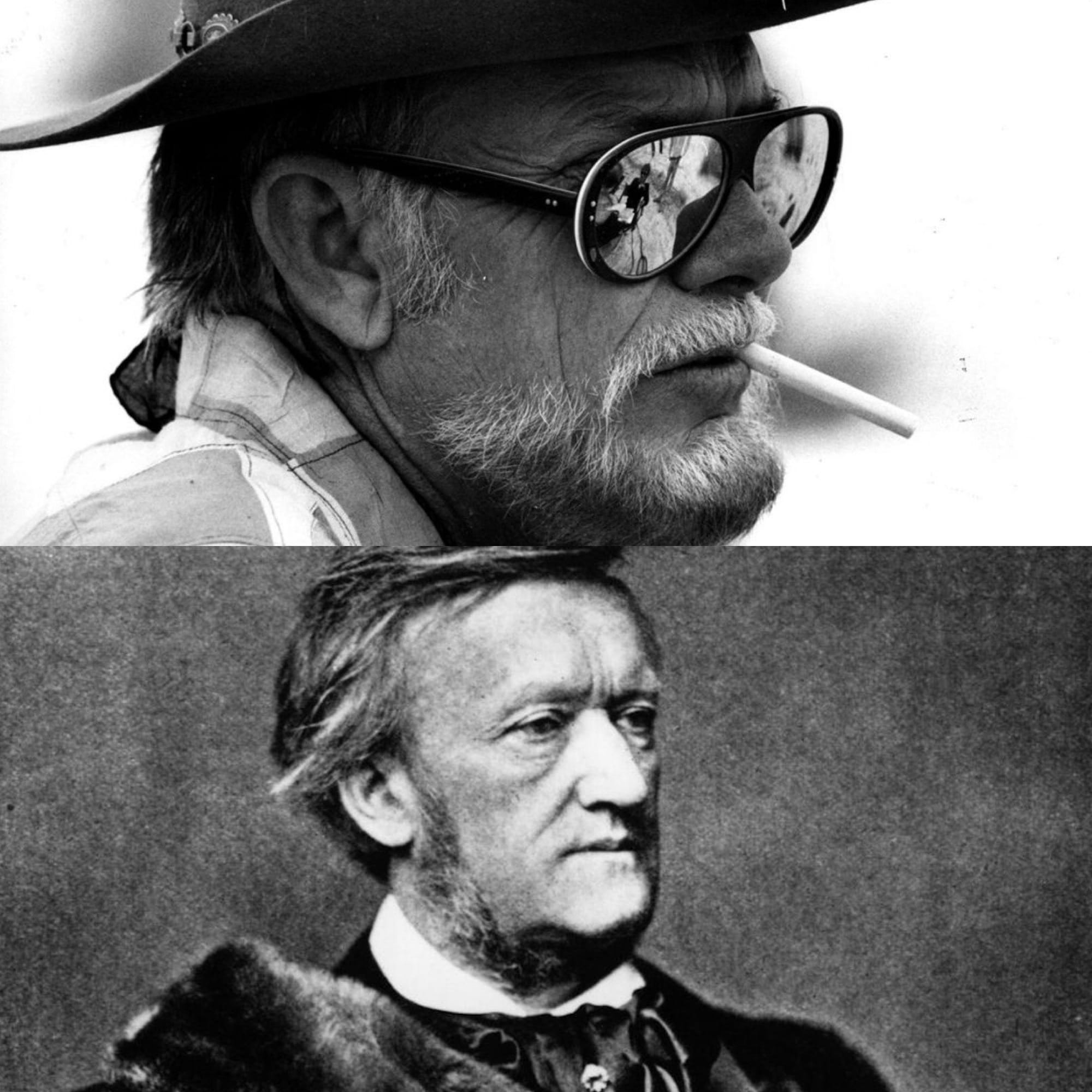

Both men (Wagner and Peckinpah) broke with the tradition of the old forms and, out of the destruction of these models, forged a new direction in both music and cinema. Just as Wagner's Ring Cycle explores themes of power, fate, and the decline of gods and heroes, The Wild Bunch similarly examines the fall of aging outlaws in a changing (and increasingly modernised) Wild West. The spectre of the Industrial Revolution could also be said to haunt the protagonists of both works in different ways.

A key scene in The Wild Bunch shows Pike and his gang encountering a motorcar for the first time—an object as alien to them as the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey is to "Moon Watcher" and his band of primal apes. When Richard Wagner visited London in 1877, he remarked to his wife, Cosima: "This is Alberich's dream come true—Nibelheim, world dominion, activity, work, everywhere the oppressive feeling of steam and fog." This astute observation demonstrates how the industrial landscape of London, characterised by its relentless labour and pervasive steam and fog, resonated with Wagner's artistic vision for Nibelheim—a realm dominated by ceaseless industry and oppressive conditions.

Perhaps both men were learning to navigate their own uncertainties about the future by addressing them through mythologies they could understand. Whether dealing with gods or cowboys, both Wagner and Peckinpah were controversial, maverick figures who found themselves at odds with the status quo of the forms they mastered and ultimately made their own. Each bridged the transition from one age to another in their respective genres, extending the dialectic and mythology of their chosen archetypes through time. These artists learned that you can't hold onto anything forever—and if you don't relinquish your attachment to the past, you'll die with it (metaphorically), or in Steve Judd's case, literally.