THE SAINT OF SIERRA MADRE

Since losing all the gold from his dramatic expedition in the mountains of Sierra Madre, the ageing prospector, Howard, had inadvertently become the richest man in the world, after being made an honorary member of the Indian tribe he had helped by recovering an ailing child from the village of Amapuli.

The villagers believed they had witnessed a miracle that long night when Howard brought the sickly child back from the brink of death after a drowning incident.

What they weren't to know was that the prospector had once lost his own child many years before and in saving their child, he was saving some part of himself that had been lost for many years.

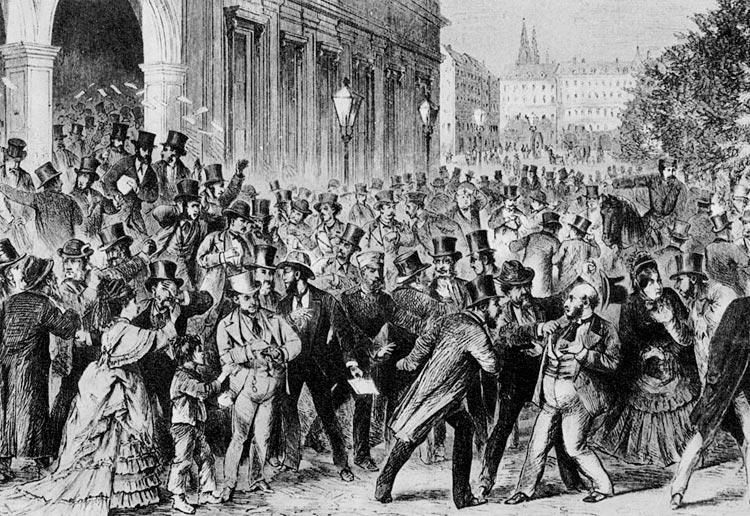

The year of the 1893 crash had brought the economic equivalent of a tsunami for millions of hard working Americans who had gone from seeing the gilded age of the 1870s and 1880s vanish in a puff of smoke as it was replaced with mass unemployment, bleak poverty and homelessness.

Having lost his own small railroad construction company in the wake of the crash, Howard found himself in a desperate situation of his own. With a wife still grieving for their dead infant daughter, he now had to find ways to reassure her that all was not lost with regards to the future.

But her faith had now been simultaneously rocked by personal and national events and he had, at least to her mind, foolishly dipped into most of his remaining savings to help the workers he would now have to lay off. His philosophy of life (which he'd inherited from his late father) was that there was always someone worse off than you whom you should lend a helping hand to but now he had tested that creed to the limit and his wife was unhappy with him about it.

"You're too saintly, Howard. You think a God who takes our child from us cares for your good turn for people who will probably spend it on drink and gambling?"

Howard loved his wife but he was heartbroken to see her become so cynical towards people. He remembered how happy she used to be when they would spend their Sundays in the park, picnicking with their young daughter under the shade of the cherry blossom trees by the lake.

How simple and innocent everything seemed those years before the crash.

And now Howard had become as much a target of his wife's bitterness as the workers she accused of taking advantage of his kind heart. In some ways, it was like the woman he had originally fallen in love with had now become a stranger, clearly overtaken by a profound grief which had cast its long shadow across her once effervescent personality.

Looking back he should have seen it coming. He later blamed himself for being so naive about his wife's suffering.

Having been forced to sell their dream house at a rock bottom price, he'd returned home to tell Mary about the confirmed sale.

He had noticed it was unsually quiet when he entered the lower hallway.

"Mary?"

The sound of the grandfather clock chiming the hour caught him unawares as he felt suddenly tense in his body, sensing something was amiss.

Noticing the door of the kitchen was wide open, Howard headed out into the back garden where to his horror he saw his wife collapsed on the ground amongst the billowing bed sheets hung out to dry on the washing line.

Finding no active pulse and seeing her wide eyes unblinking, he screamed her name whilst shaking her, in a desperate attempt to wake her up but all of his frantic attempts were in vain as after an hour of trying to save her, he finally conceded defeat.

Later, on the kitchen table, he found she'd written a short note which his tears blotted as he read it to himself.

"The pain was too great for me to continue. Don't blame yourself, Howard. I do love you."

He sat all night with his beloved Mary laid out on the kitchen table before he finally called the doctor and funeral director out to the house the next morning.

When the autopsy report of her death had been completed, it was found that Mary had consumed a lethal amount of arsenic trioxide. On further investigation Howard discovered she had been slowly accumulating a stock pile of the poison from the local pharmacy, claiming that she was trying to deal with an ongoing rat infestation in their house.

Suicide had been on her mind for a long time it seemed and that made Howard feel even worse about not reading the signs sooner.

Disposing of the numerous bottles of arsenic he discovered secreted away in the hollow of a tree in the back garden made Howard feel an unbridled hatred of the chemical.

Howard knew a good deal about arsenic from his days studying minerals with his father as gold, a particular obsession for him, could often be found with arsenic which is why he knew that many gold miners and others had been at risk from poisoning.

He didn't make the connection back to Mary's death until many decades later in the mountains of Sierra Nevada when he, Dobbs and Curtin had found their treasure and it gave him pause.

After burying his wife next to his dead child in the cemetery next to the park where they would picnic, Howard found he, too, had less reason to believe in God or any form of higher power and now found himself understanding Mary's loss of faith even better than before she died.

"I'm learning to my cost what you were trying to tell me, Mary. I should've listened better."

The only comfort Howard found that day was the red, blue and yellow light streaming through a stained glass window of a small Mexican church that filtered onto the prayer-like shape his hands had made from where he was sitting on a street bench outside.

In the subsequent years after Mary's suicide, Howard became a drifter, wandering through Texas to Mexico where he undertook back breaking construction jobs and the occasional speculative business in gushers to forget the pain of losing his wife and child.

But he knew he was no longer a young man and that he would have to diversify his survival skills in order to remain alive.

Having studied geology and mineralogy when he was young with his father, who had occasionally taken him on prospecting expeditions up the Llano River as a child, Howard now felt a desire to apply some of that rare knowledge into practice which he did with some varying success.

With at least a dozen perilous expeditions under his belt searching for gold, Howard had learnt a lot about humanity and man's greed on each of these adventures. Sometimes he found himself in profit, sometimes penniless but throughout he remained unchanged. Always the same dependable, indefatigable Howard.

And when he did have gold, his better nature always found a way to frit his treasure away as he if he was testing his own stamina and resilience to survive against the odds and rebuild time and time again.

"You can't change who you are."

Now, an old man, living amongst a tribe of Indians in Amapuli, Howard often thought about how he had never been able to truly change who he was, in spite of losing so much at the expense of his innate kindness.

Dobbs hadn't been able to change who he was either, but his particular characteristics had led him to be killed as a consequence.

Howard, on the other hand, found he had been rewarded with the trust of an entire village and would not have to lift a finger ever again in his life.

As he rested in his hammock with the bright sunlight filtering through a dyed soft fabric above him, he noticed the same colours of the stained glass from that day outside the Mexican church were now covering his face and arms.

Perhaps God was finally looking out for him after all.