THE DISCONTENTS

In researching ideas for my first novel, I've been following Timothy Leary's advice over the past week—"tuning in, turning on, and dropping out"—by studying the "social outsider" genre in film and rewatching Vincente Minnelli's Some Came Running, Bob Rafelson's Five Easy Pieces, Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon, and, perhaps lesser-known, Jack Gold's The Reckoning.

A common theme running through all four films is men caught in both external and internal conflict—drifting through life without ever finding a place to settle, either literally or metaphorically. Each protagonist manages to alienate those who try to get close to him, whether it's Ginny Moorhead (Shirley MacLaine) or Gwen French (Martha Hyer) in Some Came Running, Rayette Dipesto (Karen Black) in Five Easy Pieces, or Lady Lyndon (Marisa Berenson) in Barry Lyndon. What is it these men are so afraid of giving up to these women? Perhaps the one thing they love more than anything—their personal freedom. The irony, of course, is that their illusions of freedom come at a heavy cost, ultimately forcing them either to meet tragic circumstances or to run from any substantial connection, leaving them bound to their own perpetual isolation.

Class also plays a significant role in shaping these characters' troubled journeys, whether through the constraints of their working-class or middle-class classifications, which often feel too restrictive for their unique sense of individuality. This, in turn, exacerbates their refusal to become what they believe their partners, communities, or society expect of them.

In Some Came Running, when Dave Hirsh (Frank Sinatra) accidentally returns to the town where he was raised via a Greyhound bus, he immediately finds himself at odds with the conservative social mores that make hypocrites of those desperately trying to maintain decorum. He knows all too well that behind closed doors and lace curtains, they are just as flawed and human as anyone else. Yet, at the same time, he finds no real home among the drunks and prostitutes he associates with, leaving him with nowhere to truly belong.

Similarly, Bobby in Five Easy Pieces oscillates between disdain for the "slobs" he works with in the oil fields and those he socializes with in bowling alleys. However, when he reunites with his upper-middle-class family, he is equally repelled by what he perceives as their snobbery. As a result, he becomes a man stranded between two worlds, belonging to neither—a solitary figure adrift in his own desolation.

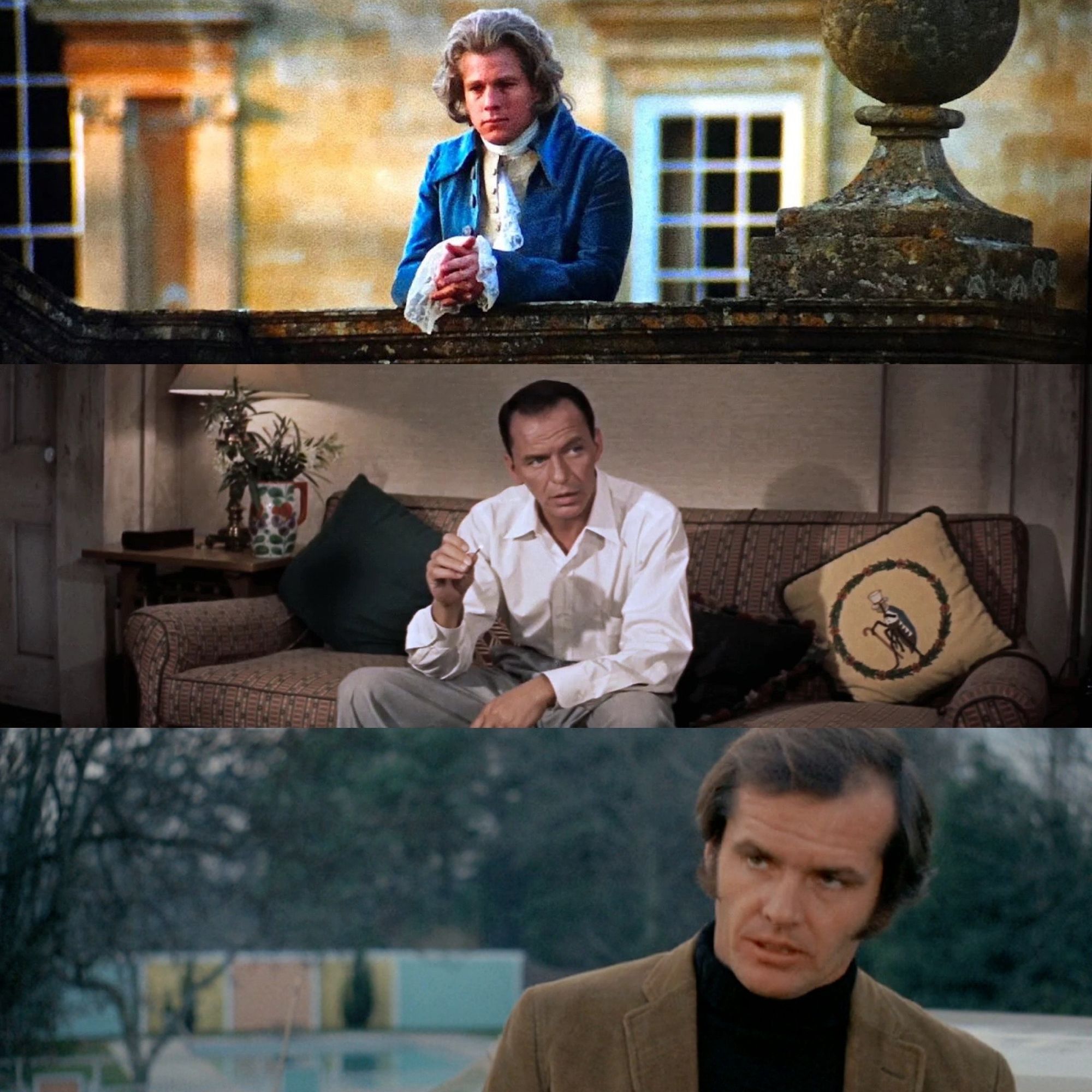

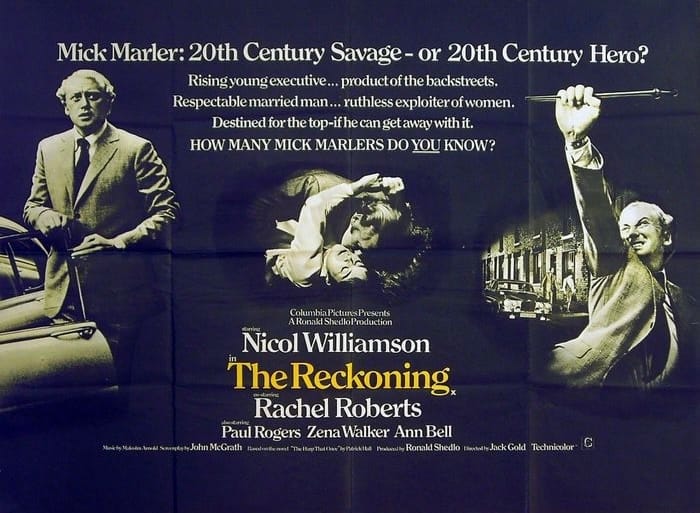

Both Barry Lyndon and The Reckoning explore themes of social mobility, albeit in different ways. Barry ascends the social hierarchy of the 18th century through historical happenstance, fate, charm, and deceit, rising from near-Irish peasant to European aristocrat. Meanwhile, Michael Marler (Nicol Williamson) works his way from the industrial North to the affluent South of England in 1960s Britain, securing a high-level executive position. However, when he returns to his working-class roots in Liverpool after his father’s death, he realises he is still the same person he was before, igniting an internal conflict between the two vastly different worlds he inhabits. Barry's base and unrefined characteristics are exposed by the defiant Lord Bullingdon (Leon Vitali) in front of a drawing room filled with aristocrats, resulting in a scene of violence resembling a barroom brawl. Kubrick brilliantly captures this raw action by utilising the disorientation of a hand held camera, in contrast to the painterly formality of much of the rest of the movie's cinematic compositions. It could be said that Barry belongs as much to the Angry Young Men brigade of the 1950s and 1960s as to his own time. Even though he is from another century, the archetype is timeless.

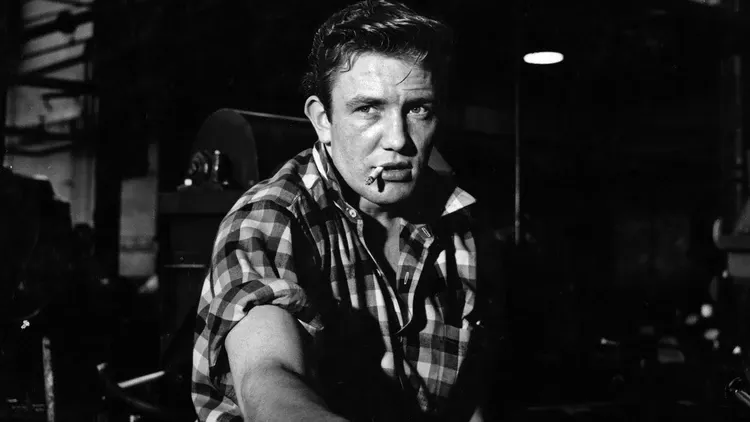

And if Lucky Jim, Jim Porter, and Arthur Seaton—those sullen icons of the Angry Young Men literary movement—heralded over a decade of class defiance in film and fiction (mostly the 1960s), then it was Michael Marler who ended it. On the cusp of the 1970s The Reckoning bleakly suggests that there is no real escape (other than death) from the environment and family that shaped you. Bobby Dupea in Five Easy Pieces also attempts to exist outside of class entirely, but in so doing requires severs all attachment to people and places, leaving him utterly untethered and alone.

As for Dave Hirsh in Some Came Running, when he finally attempts to overcome his own ingrained snobbery and marry Ginny Moorhead, he learns the hard way that defying an entrenched class system can lead to tragic circumstances.

The moral of all four of these outsider stories seems to be: accept your fate regarding social status and environment, or suffer the consequences. By stark contrast, George Bailey (James Stewart) in Frank Capra's It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) nearly throws himself off a bridge before realising the abundance of what value he already has close to him—his wife, Mary (Donna Reed), his children, and the close-knit community of Bedford Falls.

Unfortunately for Barry, Dave, Michael, and Bobby, they pay a much heavier price for their social suffocation and rebellions.