FROM FLEAS TO DINOSAURS

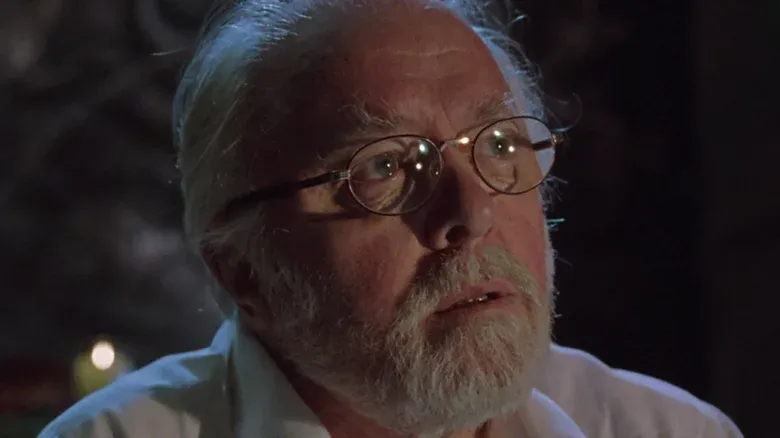

"I wanted to give them something that wasn't an illusion, something that was real." - John Hammond

Considering that in 1993, Steven Spielberg released both Schindler's List and Jurassic Park in the same year, it’s easy to overlook that some of his best directing comes in the more overtly "popcorny" of the two movies. In a film that features so many successive action set pieces—particularly in its second half—it always surprises me that one of the most suspenseful moments in Jurassic Park is the quiet two-hander scene shared between eccentric entrepreneur John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) and paleobotanist Dr. Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern).

In this eerie scene, the two characters sit across from one another at a dining table, where Hammond is comfort-eating from pots of melting ice cream— a result of the power outage at the park. This outage, caused by the devious internal sabotage by Dennis Nedry (Wayne Knight), has forced Hammond to rescue the ice cream, even as his missing grandchildren represent a far more pressing concern. It takes Ellie to point this out to him, which says a lot about Hammond’s state of mind at this moment, teetering on the brink of losing his most ambitious project—a dinosaur theme park.

Even before we find Hammond with his various tubs of ice cream, we see Jurassic Park merchandise on the walls of the visitor center. No doubt this merchandise would seem alluring to children watching the movie, despite the cautionary tale the story presents. Profit would inevitably be made outside the cinema, adding an extra layer of delicious irony.

Suspension of disbelief in a film like Jurassic Park is certainly a high-wire act, and this quiet scene between Hammond and Sattler risks blowing it, as the audience's critical thinking begins to return after nearly an hour of extreme action and suspense. And yet, in the hands of a master director like Spielberg, we buy into this scene precisely because it feels so bizarre and distinctly different from the action-oriented sequences that precede it. It’s an unusually disquieting moment because, even as Hammond reflects on his failed project and the origins of his inspiration, we are acutely aware that other characters are fighting for their lives on a storm-swept island overrun by rampaging dinosaurs.

Strangely, it reminds me somewhat of the later scenes in Apocalypse Now, where Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando) is mumbling and philosophizing in the shadows of his temple-like structure on his fortified island compound, while Montagnard tribespeople and Cambodian villagers protect him and adhere to his authority.

And yes, of course, there’s a touch of Dr. Moreau from The Island of Dr. Moreau in Jurassic Park, which also bears comparison with Kurtz. Funnily enough, Brando played Moreau in John Frankenheimer’s 1996 film production. There are no such things as coincidences in Hollywood, surely?

Remembering Petticoat Lane

"You know the first attraction I ever built when I came down south from Scotland? It was a Flea Circus, Petticoat Lane. Really quite wonderful. We had a wee trapeze, and a merry-go... carousel and a seesaw. They all moved, motorized of course, but people would say they could see the fleas. "Oh, I see the fleas, mummy! Can't you see the fleas?" Clown fleas and high wire fleas and fleas on parade... But with this place, I wanted to show them something that wasn't an illusion. Something that was real, something that they could see and touch. An aim not devoid of merit." - John Hammond

From one of the smallest insects (a flea) to one of the largest carnivores (T-Rex) in the history of the world, John Hammond finds a commonality in his desire to present an attraction of nature that the public will enjoy as entertainment. Alas, the folly of this desire lies in his own hubris, and the current destruction unfolding around him while he eats melting ice cream attests to the inevitable downfall of his latest "circus." It is Hammond's inherent flaw in his ambition that could make his and the other human lives extinct now, while unleashing new, genetically modified monsters from ancient history.

N.B.: It is interesting to note that earlier in the film, there is a passing reference to J. Robert Oppenheimer in the form of a photograph attached to a computer monitor.

The scene takes on added dimensions when one considers that Spielberg is directing another film director (Attenborough), who belongs to an older generation of filmmakers. Spielberg is unleashing his own computer-generated monsters with Jurassic Park, a move that would have significant consequences for the future of the film industry—yet recognizing that all of it is an illusion, much like the fleas in their circus on Petticoat Lane. I've often thought Jurassic Park works as a metaphor for Hollywood itself, where Hammond's island is the testing ground or screening room for a film that hopes to make money without scaring off both its target demographics and the critics simultaneously. Dr. Alan Grant (Sam Neill), Dr. Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum), Donald Gennaro (Martin Ferrero), as well as Ellie and Hammond's grandchildren, are all essentially bearing witness to a preview screening of the final product, just as we, the audience, are watching them react to it—a sort of meta-movie device.

Considering the heavy burden of making Schindler's List as a cinematic testimony of the Holocaust, it's worth noting that Spielberg would have been putting the final post-production touches on Jurassic Park while preparing to shoot on location in Poland for Schindler's List. Perhaps his differentiation between personal ambition, human history, and entertainment was a moral conundrum (much like it is for Hammond) that he had to wrestle with in his mind.

Of course, Hammond and his remaining company evacuate the island at the end of the film, leaving the dinosaurs to destroy themselves. Spielberg, however, will be far more reluctant to leave Hollywood, even with its ever-present monsters.