HEAVEN AND EARTH

“There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” - Hamlet

Perhaps because I’ve recently watched the entire Ingmar Bergman canon in sequential order, the effect of finishing with his magnum opus, Fanny and Alexander, felt even more overwhelming this time around. It truly contains multitudes, in the way the greatest art should, and transforms you in the process of watching it.

What makes it especially moving is that after five hours of drama it offers the central characters an opportunity to return to a familial equilibrium (a Heaven of sorts) that, for so long in the story, seems an impossibility to reach. Could it be an act of Alexander’s imagination (Bertil Guve) that creates the conditions to flee Hell (or purgatory) under the strict authoritarian rule of Bishop Edvard Vergérus (Jan Malmsjö)? When Vergérus tells Alexander’s mother, Emilie (Ewa Fröling), that the young boy scares him, we don’t doubt that he is aware of the mysterious power that lies in the child’s imagination—that mystical, almost supernatural realm of the mind of which Alexander (see Bergman) reigns supreme. The film begins with Alexander looking through a toy theatre, observing as a God of sorts.

Unlike the tragedy of Hamlet, which the film alludes to often, Fanny and Alexander finds resolution in a way that feels as magical as Dorothy returning home from her adventures in Oz, but with a Bergman-esque twist. Here, he presents the great existential themes of his life: the artist versus God, and how an imperfect soul such as an artist can find peace on earth when the promise of Heaven and the threat of Hell are ever present—both in life and in the heart and mind.

When we are finally reunited with Alexander’s family in the final act and epilogue of the film, we, the audience, have traversed Heaven and Hell to get there with him, his sister Fanny (Pernilla Allwin), and his mother Emilie. After all the trials and tribulations of living under the Bishop’s strict rule in his austere home, the colour of the Ekdahl household floods back onto the screen, and we are reminded how important what once seemed trivial truly is—an imperfect paradise we can all still find on earth.

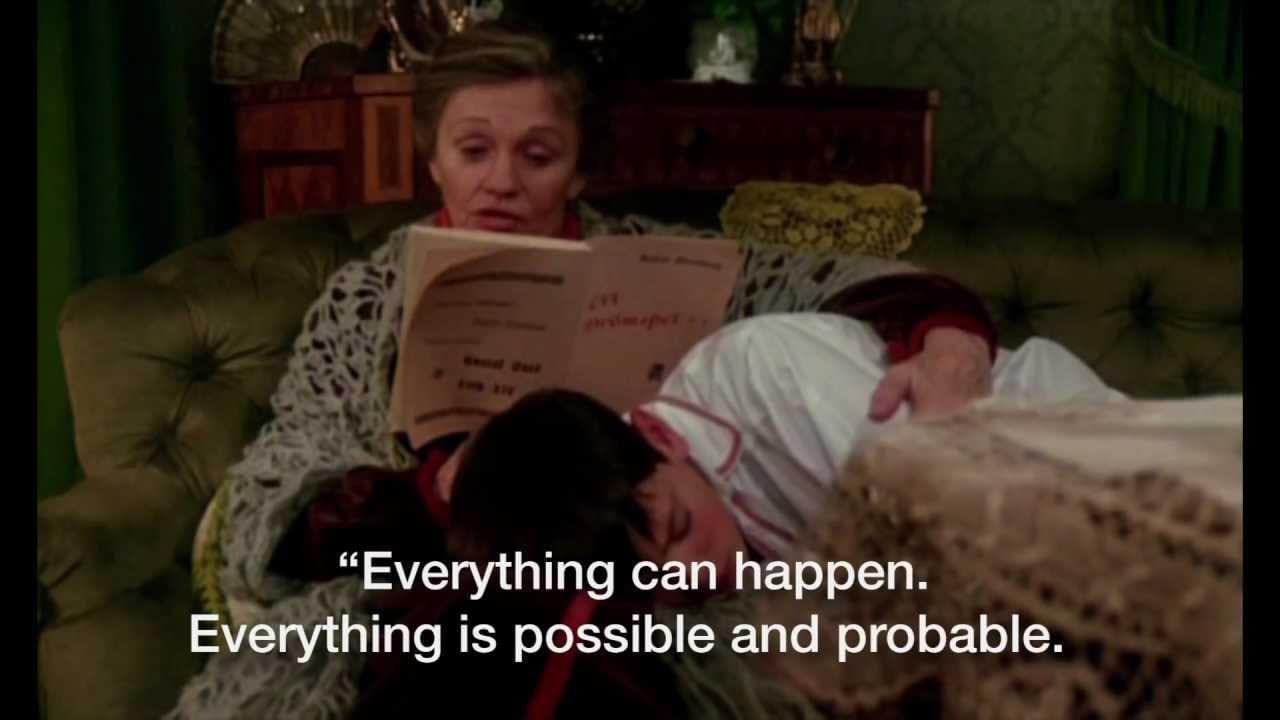

The closing image of Alexander resting his head on his grandmother Helena Ekdahl’s (Gunn Wållgren) lap while she recites the opening words of Strindberg’s A Dream Play demonstrates how the universe is contained in the mind of a child, and how, for Alexander, the need to dream is essential in order to create. Just prior to this serene moment of contentment, Alexander sees the ghost of the dead Bishop warning him that “you will never get rid of me,” a figure that stalks and haunts the young boy much like Death does with the knight Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) in Bergman’s 1957 masterpiece The Seventh Seal. Of course the artist is forever plagued with doubt, insecurity and the threat of mortality.

But for me, it was Gustaf Adolf Ekdahl’s (Jarl Kulle) life-affirming closing speech at the family dinner table, where he reminds everyone that “evil is breaking its chains and running through the world like a mad dog,” and that (to paraphrase) we must protect and cherish the small things that bring us happiness in life that finally broke me down.

It did me good to hear these words at Christmas. I share them with you in the hope that they resonate in your heart too.

My dear, dear friends. I am moved more than I can say. Dear friends, dearest Mama, my greatly loved wife Alma, my darling Emilie, more beautiful than ever, my wonderful children Petra and Jenny, and little Miss Helena Viktoria, no less, lying there as good as gold in her cot, and dear Maj, whom I am so very fond of! Not forgetting my incomparable brother and his sweet wife and my highly esteemed friend Isak Jacobi, who has rendered immeasurable service to this family, dear Vega and Ester, and all you good friends who so loyally help us up the hill of life. Last but not least, those dear and admired and greatly talented and superb actors, Mr. Landahl, Miss Schwartz, Mr. Mors- ing, and Mr. Bergman. If I could I would throw my arms round you all in a vast embrace and I would plant a kiss of affection on your brows, a kiss that, more than any words, would tell you of my happiness and my love. We are all together again now. Our little world has closed round us in security, wisdom, and order after a time of horror and confusion. The shadows of death have been routed, winter has been put to flight, and joy has returned to our hearts. Now I must lift Miss Helena Viktoria up from her cot—is that allowed? I knew it would be. Amanda, go and get little Aurora and nurse her in your lap; she is not to feel forgotten on this happy day, the best day of my life. Now I’m going to make a speech. Look, she’s laughing at me, my daughter Helena Viktoria. Go on, laugh at your old father and never mind what he says. It’s all nonsense! (His eyes fill with tears)

My wisdom is simple, and there are no doubt people who despise it. But I don’t give a damn. Forgive me, Mama. I see you raising your right eyebrow; you think your eldest son is talking too much. Don’t worry, I’ll be brief. Well now, we Ekdahls have not come into the world to see through it, never think that. We are not equipped for such excursions. We might just as well ignore the big things. We must live in the little, the little world. We shall be content with that and cultivate it and make the best of it. Suddenly death strikes, suddenly the abyss opens, suddenly the storm howls and disaster is upon us—all that we know. But let us not think of all that unpleasantness. We love what we can understand. We Ekdahls like our subterfuges. Rob a man of his subterfuges and he goes mad and begins hitting out. (Laughs) Damn it all, people must be intelligible, or we don’t dare either to love them or speak ill of them. We must be able to grasp the world and reality, so that we can complain of its monotony with a clear conscience. Dear, splendid actors and actresses, we need you all the same. It is you who are to give us our supernatural shudders and still more our mundane amusements.

The world is a den of thieves and night is failing. Soon it will be the hour for robbers and murderers. Evil is breaking its chains and goes through the world like a mad dog. The poisoning affects us all, without exception, us Ekdahls and everyone else. No one escapes, not even Helena Viktoria or little Aurora over there in Amanda’s lap. (Weeps) So it shall be. Therefore let us be happy while we are happy, let us be kind, generous, affectionate, and good. Therefore it is necessary, and not in the least shameful, to take pleasure in the little world, good food, gentle smiles, fruit-trees in bloom, waltzes. And now, my dearest friends, my dearest brothers and sisters, I’ve done talking and you can take it for what you like—the effusions of an uncouth restaurant owner or the pitiful babbling of an old man. It doesn’t matter to me, I don’t care one way or the other. I am holding a little empress in my arms. It is tangible yet immeasurable. One day she will prove me wrong, one day she will rule over not only the little world but over—everything! Everything!