CARLOS KLEIBER & THE WALTZ OF DEATH

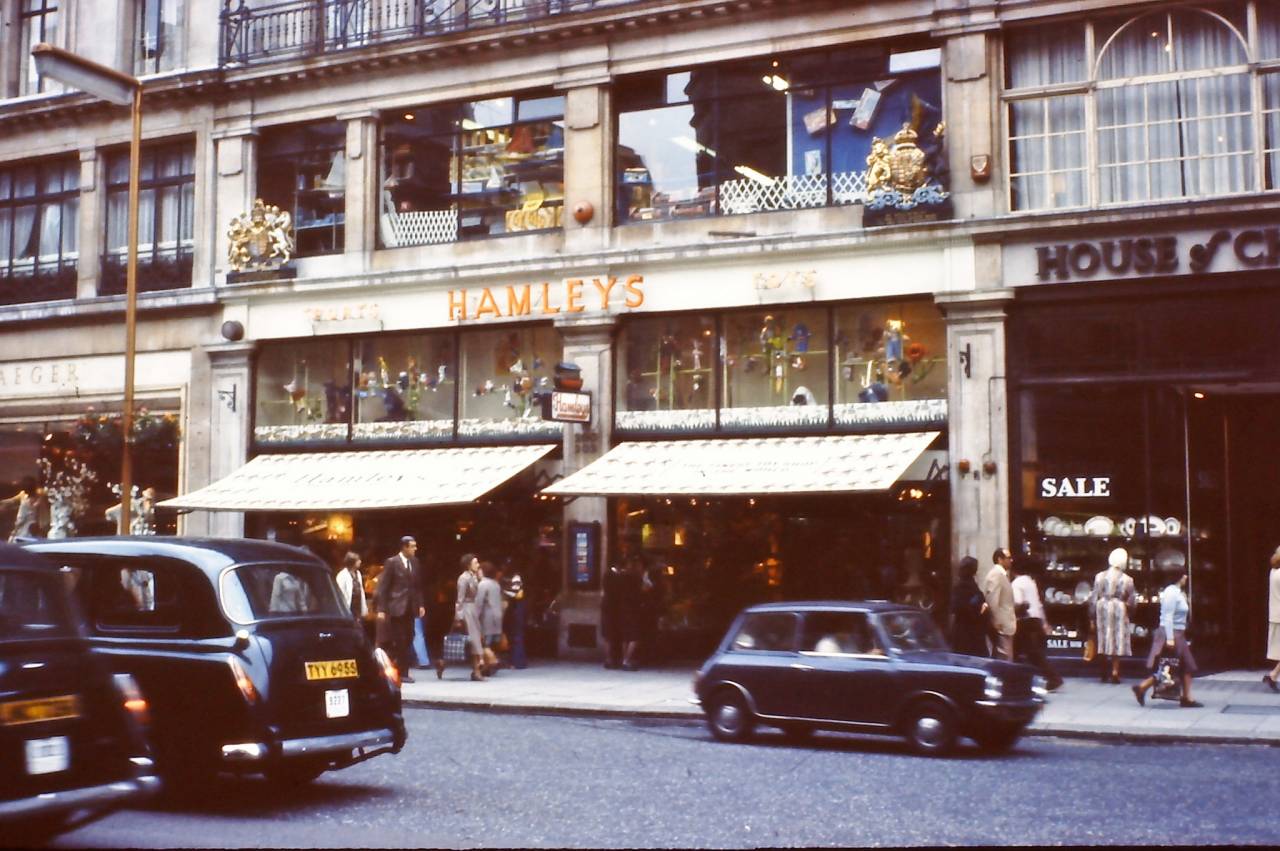

The year was 1979 and world-renowned conductor Carlos Kleiber was shopping for presents for his children in Hamley's toy shop, Regent Street before rehearsals began for Puccini's 'La Boheme' at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden.

As much as he was a devoted professional (sometimes too much so) when under pressure to commit to a new concert or opera performance in public, he loved any opportunity he could find to escape the fame that inevitably went with being so well known. Being a child prodigy and the son of a legendary conductor had meant that Kleiber's life was destined for scrutiny one way or another. Though he knew he would be ill-suited to any other line of work, he also often feared his perpetual tight-rope walk along such exalted heights of cultural excellence. There was an exhaustion that came with always reaching for the ecstatic. Sometimes he wished he could just be in the audience listening purely to the music as a non-musician without all the pressure of being an acclaimed conductor who people expected glimpses of heaven from. He wasn't being facetious or ungrateful. He just knew that he could never afford to be mediocre or average.

He had to be, at all times, perfect.

There were no rivals amongst him that he felt intimidated by.

Only himself and his father Erich.

As Carlos looked amongst the rows upon rows of shiny new toys on display, his eye was drawn to an ornate toy carousel music box. Winding it up, he was beguiled by the rotating metal pins that played Strauss's 'An der schönen blauen Donau' (The Blue Danube), a miracle considering he had heard that particular piece of music more than practically all the others in his life including Beethoven's '5th'.

He could remember his father conducting the piece when he was a young boy watching his rehearsals from the secret places he'd like to sit in the concert hall. Although it was in many ways a commonplace melody, he'd always loved it and found it lifted his spirits whenever he heard it.

But suddenly, a most strange phenomenon occurred and one that disturbed the maestro greatly. The notes of the music box turned from the original key of D major to a discordant D minor sounding more like a funeral march than the life-affirming waltz he'd always known it to be.

He tried to slow down the music with the windup key but it only got faster, as the carousel with its miniature fairground horses speeded up, spinning round and round. As his own heart began to race he looked around for help from a shop assistant, but no one was nearby.

Suddenly, he looked up at the light fittings above him and felt disorientated as his surrounding environment appeared to be constantly moving.

At this point, the conductor collapsed on the fourth floor of the toy shop and finally, a shop clerk appeared to attend to him.

"What do you think it means?" Kleiber asked his therapist on the phone from his hotel room in London later that evening.

"I think it means you're anxious and your body is finding ways to release some stress."

Kleiber took a sip of whiskey from a crystal tumbler while clutching the red handset of the telephone under his arm.

"But why the waltz?"

"You remember how you told me you would always watch your father in rehearsal and think that he was controlling the musicians magnetically from his stick?"

Kleiber smiled.

"Of course. He was controlling all of their brains all at once."

"Well, perhaps you felt anxiety about not being able to control the orchestra as effectively as your father. You're worried about losing control. The fear of not being able to live up to your father is a re-occurring issue we've discussed many times, Carlos."

The conductor curled the telephone cord around his finger and looked out at the window on the bustling city below.

"Well, silly me for forgetting to pack my anxiety meds. I'll see if I can find some street corner to procure some from."

"You're joking?"

Kleiber enjoyed the silence as he waited for his therapist to determine if he was joking or not.

"You see. That's the problem with you therapists. You're always so serious."

"We're serious because we see people in psychological distress."

Feeling suddenly restless, Kleiber was keen to end the conversation.

"Well, I should go really Eric. I should rest before tomorrow."

"Distraction is key for your stress. Find ways to focus your attention away from those demons in your head."

"I will. And thanks!"

Kleiber replaced the phone receiver on the handset and started to instantly hum the Der Fledermaus waltz to himself.

As he headed to turn the television on, he noticed the Hamley's bag on the coffee table and stared at it.

Easing out the contents from the bag, he was immediately reacquainted with the carousel music box.

Placing it on the table he looked at it and then began to wind it up but to his great surprise, it didn't turn and remained completely motionless.

"What is this madness?"

Picking it up and turning it upside down he tried to turn the windup key once more but it remained stubbornly locked.

"Cursed thing!"

Irritated by the dysfunctional toy he put it back on the coffee table and spent the rest of the evening finishing off his whiskey whilst trying to make sense of British television.

Later that night the conductor had a strange dream.

In it, he was sat atop a merry-go-round horse and attempting to conduct an orchestra that was watching him from the chairs on which they sat as he span round and round.

The carousel got faster and faster until he held onto the pretend horse for dear life, petrified he would fall off.

Having fallen asleep in his clothes on top of his hotel bed, Kleiber woke up in a cold sweat, alerted to the sound of the music box playing in the room next door.

As the rotating cylinder plucked the protruding pins of the steel comb playing the all too familiar theme of the Blue Danube, Kleiber got up off from his bed and went to pick up the toy he'd believed was broken.

"Madness!"

Heading to the window and sliding up the sash frame, he dropped the music box onto the pavement far below where it shattered into a hundred pieces.

"Now you can stay broken!"

"Can you talk Eric?"

"I'm half alseep but I can grunt maybe?"

Having been fast asleep in his bed in his Munich home, Eric had only a few clients he had given his personal number to in the event of an emergency. Kleiber was one of them.

The conductor was relieved to hear his therapist's voice, and went on to explain the odd occurence of the dream and the music box with its mind of its own.

"What does it mean? Am I losing my mind?"

"We've been here before Carlos. Your anxiety is running high. The mind can play strange tricks when our nerves are in a bad way like this."

The conductor was becoming frustrated with his therapist's general, non specific analysis.

"So, is there something wrong with me?"

"Yes. You're far too talented. I wish I could conduct Tristan like you. Alas, I can barely navigate my way through the Moonlight Sonata."

"I don't need flattery right now. I don't pay you for that."

Sensing his client's impatience for a concise assesement of the situation, Eric had no choice but to give his client a verbatim, sleep deprived interpretation.

"The music box is your career. Your fear is losing control of all that you have won acclaim for. The fact the music does not co-operate when you want it to is similar to that of a stubborn horse, similar to those fairground horses you saw spinning fast or unmoving."

"Or perhaps it's my fear of death?"

Eric was taken aback.

"How do you mean?"

"When the music stops, I no longer exist. The pressure to keep the music playing is for me the only way I can stay in control. But when it's out of control I am faced with my biggest fear. No longer existing. The minor inversion of the Blue Danube is symbolising the very opposite of life. Why else would such a jolly tune as the Blue Danube sound like a speeded up funeral march?"

There was a notable silence for a moment as Erik felt undone by his client's more accurate assessment of the dream and the music box which he then proceeded to further elaborate on.

"Perhaps it's a premonition, yes? " Kleiber asserted.

"Well, you're back in Munich in a few weeks. How about we have a proper face to session then. I'll have time to properly mull it over."

But Eric was suddenly met with a flat dial tone ringing in his ear.

"Carlos? ... Carlos?"

The year was 1989. It was the New Year's Day concert in Vienna and Carlos Kleiber was at the conductor's podium drawing waves of beautiful sounds from his most beloved Vienna Philharmonic as Strauss Waltz after Strauss Waltz heralded the arrival of the new year with elegance, exuberance and hope.

When it came to the final An der schönen blauen Donau, Kleiber revelled in its expansive lines and closed his eyes in near ecstasy.

But as the melody took full flight, Kleiber recalled the strange episode in London all those many years ago and was suddenly seized with an internal panic inside his head and his heart.

A conflict was now brought into focus as the present moment of optimistic abandon was met with his memory of that supernatural occurrence, one that the conductor still did not fully understand but intuitively believed to be a premonition of some sort.

Maintaining control whilst falling apart is the very definition of professionalism and as he created delight for the audience behind him, Kleiber knew that his demons were also present.

This was the music of heaven played by a man who was simultaneously in his own personal hell.