MONKEY BUSINESS

Sometimes I like to daydream about which historical celebrities I would invite to a hypothetical dinner party and invariably I arrive at the same three characters each and every time - Orson Welles, Elmyr de Hory and Clifford Irving - all three men who coincidentally happen to appear in 'F For Fake', Welles's masterpiece film essay from 1973.

If you're not acquainted with the film then all I can say is it's truly one of the great delights of Orson Welles's canon and unequivocally my personal favourite tied alongside his 'Chimes At Midnight' (1965).

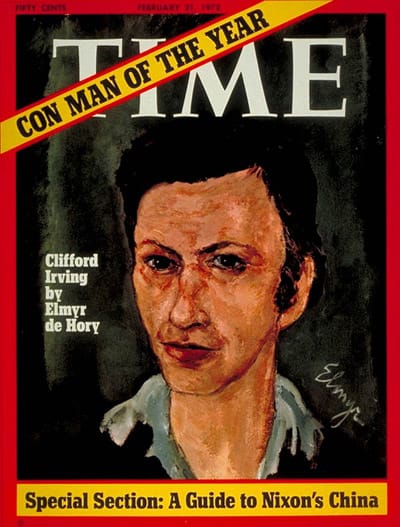

All three men in 'Fake' were master deceivers. Welles tricked the American nation into believing aliens were invading the country in his famous 1938 radio Halloween broadcast 'The War Of The Worlds' while Elmyr de Hory made a mockery of the major art galleries of the world by selling imitation Modigliani, Matisse, Picasso and Renoir forgeries. Clifford Irving (see photo above) was perhaps the most complex of the three men, achieving fame and notoriety for his fake, yet highly convincing biography of recluse billionaire, Howard Hughes which subsequently led to a bizarre television phone call in which the mysterious aviator was forced to insist that he had nothing whatsoever to do with the 'fake news' memoir. Of course, by that point Irving had achieved a sufficient amount of celebrity to dine out on at dinner parties, as he had, as fate would have it, teamed up with his neighbour Elmyr in Ibiza (where de Hory had semi-retired), having written a biography of the charismatic, art forger's life.

The pathology of con men I've always found fascinating. Welles as a magician and creative mischief maker knew that a great deal of what is presented in radio, theatre and cinema is as much about constructing illusions as it was about the artistic and entertainment factor of his productions. De Hory found a thrill in both imitating the great painters he loved as well as making a mockery of the art market itself, giving himself the opportunity to both copy the geniuses he so admired whilst also enjoying the power trip of undermining the experts supposed intelligence and unquestioned authority. Clifford Irving (who would have surely been invented by Patricia Highsmith if he hadn't already existed) saw opportunities to exploit the life of an eccentric genius in order to fulfil some aspirational ambition inside himself, something akin to an older Frank Abergnale, the baby faced protagonist played by Leonard DiCaprio in Spielberg's 'Catch Me If You Can' (2002).

I can only imagine the joy and tension of indulging in an evening with these three men whilst knocking back shots of Hierbas ibicencas, drunkenly observing the orange cointreau-coloured sunset slowly sink beyond the Mediterranean horizon . The uncertainty of deception and ego in the room would most certainly keep my wits sharp and compel me to remain a touch more sober than Welles, De Hory and Irving as I would want to study them for my triptych biography of them all.

We could surely use an Orson, Elmyr or Clifford to help navigate our way through this current 'fake century' of ours, where uncertainty about what is true and what isn't is governed not so much by artists or con men but by Silicon Valley fact checkers and bureaucratic politicians. Last week, the Mexican American boxer, Ryan Garcia reminded us of the need for illusion and madness in the world and in a sport that has often embraced the theatre of the absurd - think only of Muhammed Ali, Chris Eubank and Tyson Fury - all showmen prize fighters with a taste for abstract thinking and comedy timing. Most modern artists struggle to be as free as Garcia (who may or may not be mad), as a possible consequence of post-modernism and exhaustive meta modernism making everyone so self-aware that they think everything is now contained within quote (or quotes within quotes) marks - the very definition of the death of playful originality. By having to define the parameters in which things are always contextualised so overtly we lose the beauty in that mystery of uncertainty, the line between what is real and what isn't and what is art and what is deception.

Perhaps the moral of 'F for Fake' is that it matters not what is real and what isn't, for everything in the end will be made ultimately redundant by the passing of time, even if that means decades, centuries or millenniums.

“Our works in stone, in paint, in print, are spared, some of them, for a few decades or a millennium or two, but everything must finally fall in war, or wear away into the ultimate and universal ash - the triumphs, the frauds, the treasures and the fakes." - Orson Welles ('F for Fake')

Though I will say, my imaginary dinner party becomes more real as I write this on this bitterly cold April day and dream of clinking glasses and sharing anecdotes with Orson, Elmyr and Clifford.

Salut!