CARPE NOCTEM

1959 hadn't ended well for Mr Keating and he had retreated into his own version of Plato's cave for six dollars a night.

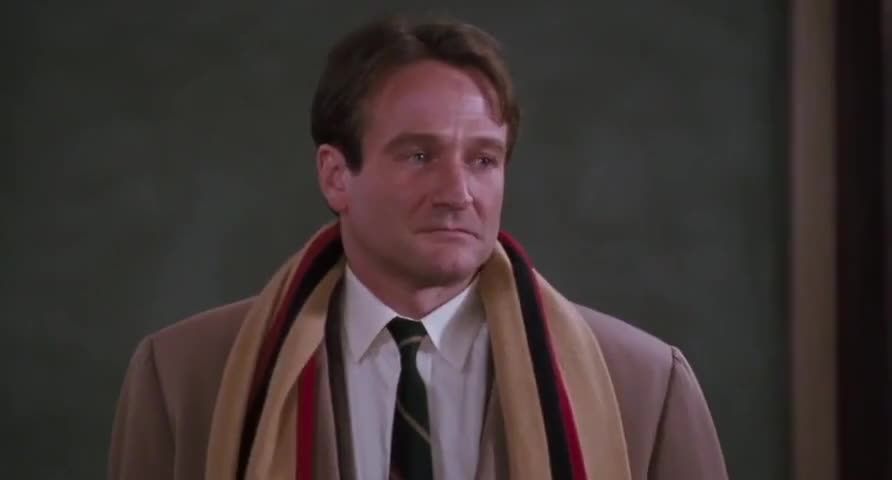

After the notorious 'Dead Poets' Welton Academy scandal concerning the untimely death of a young student, John Keating instinctively felt he needed to get away from Vermont altogether although he had struggled to decide if it was a new state or a new country he would move to next.

He had lived in England many years before his appointment at Welton and had enjoyed some of the happiest times of his life there, but something inside of him told him that returning there now would be a mistake - especially after the way things had been left with his Cambridge born ex-wife, Anne. He felt it would be like returning as Scrooge with "the ghost of marriage past" which would only increase his regret about the complete failure of their short-lived marriage.

Anne had noticed early on in their London courtship that John always seemed restless. One afternoon, enjoying tea at Simpsons in the Strand, she noticed his incessant tapping of the white linen table cloth with his fingers.

"Are you okay? You're playing the table like you're Gene Krupa."

"I am?" John said, suddenly curtailing his unconscious tapping. "I didn't even notice I was doing it."

Anne smiled and tried her best to hold John's attention with her eyes that were somewhat concealed by the dim lighting of their table lamp.

"You know, John. I've actually been making some observations about you lately."

Initially, the handsome American seemed suspicious of her claim until he reverted to impersonation as a way of deflection.

"Pray tell, Ducky, what 'ave you ascertained about me?" he said, doing his best Pearly Queen.

"Well. It occurs to me that you always appear to be looking over your shoulder, scouting for the nearest exit point in any room you're in."

"Well, see. You always got to keep your eyes on the exit, see, just in case trouble comes looking for you, see."

As he demonstrated his best James Cagney, it was clear to Anne that John deployed comic deception to hide the sadness behind his eyes. And for the most part it worked for him as whenever things got problematic, he used his comedic talent to divert further scrutiny from others.

But late at night, when they were in each others arms, she felt a heavy sense of melancholy excuding from this funny, erudite and thoughtful man yet wasn't sure any amount of love and intimacy between them would help exorcise the obvious pain he was carrying inside of him.

"You've got what my mother would call a heavy soul," he remembered Anne had told him another evening when they had attended a concert performance of Beethoven's Emperor Concerto conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham.

"That's okay," he replied. "You need a heavy soul to listen to Beethoven."

Now he was alone, far, far away from Anne in London and was listening on his portable record player to the same music they'd heard that night at the Royal Albert Hall. John realised upon reflection that she had seen right through him from the start. Maybe that was why he had to get away in the end. He was uncomfortable with people getting to see the secret side of him that remained forever broken. Though the price of heartbreak was generally felt to be beyond recompense, John gained a greater peace of mind being free from being further found out, even if he missed her terribly.

Welton found out about John, too but it was an insitution. As bonded as he had been to the place, he could always find another academy to teach at.

Then of course there was Neil.

He'd felt acute remorse about the death of his student but knew his conscience was clear. He'd spent endless nights going back through the minutiae of his conversation with Neil that night in his shoebox office at Welton.

"You're playing the part of the dutiful son. I know this sounds impossible, but you have to talk to him. You have to show him who you are, what your heart is."

Keating remembered only too well the look Neil had given him when he had made the bold suggestion. It was the look of someone imprisoned by his own fear.

"I know what he'll say. He'll tell me that acting's a whim, and I should forget it. That how they're counting on me. He'll just tell me to put it out of my mind, "for my own good."

John could relate. He had been through a similar experience with his own father but had somehow found the courage to break free, though it had come at a heavy personal cost. Perhaps that's why he found himself thinking of his own familial difficulties as he encouraged Neil to stand up to his father.

"You are not an indentured servant. If it's not a whim for you, you prove it to him by your conviction and your passion. You show him that And if he still doesn't believe you, well, by then you'll be out of school and you can do anything you want."

No matter how much he believed what he was telling Neil, he could see that the boy simply didn't believe it in his own heart.

"You have to talk to him before tomorrow night."

Keating had no children of his own but he never felt more like a father than in that painfully exquisite moment of honesty with his young student.

"Isn't there an easier way?" Neil had asked, already knowing the answer his teacher and mentor would provide.

"No."

"I'm trapped."

The thought of the young man taking his life that cold winter's night had haunted John's mind many times since the event, but mostly he knew that it would be sensible for his own self-presevation to keep some ghosts at a distance - though he found he would often still hear Neil's voice as Puck whispering to him at night.

"If we shadows have offended,

Think but this, and all is mended,

That you have but slumbered here

While these visions did appear."

It was 3am and the buzzing neon sign outside his window was keeping John Keating awake.

Pacing up and down the worn out carpet of the seedy hotel room he had been living in for far too long now, Keating was getting nervous about the direction of his thoughts lately.

Something that would steady his mind from submerging beneath the deep was the image of those boys' faces the day of his final departure from Welton. He remembered their complete and utter allegiance to him as they all stood upon their desks and saluted him. Strangely, he could almost imagine the allure for dictators when they have so well convinced the people to believe in the singular vision for their nations. But as someone who resisted authority, he knew he had no interest in being corrupted by power. That was for the Mr Nolans of this world.

John believed in freedom. Freedom without rules. Freedom without boundaries.

And though he was an individualist in so many ways he had always felt a strong desire to be subsumed into something bigger than himself. That was what the Dead Poets Society had been about originally. Connecting through affinity and organising rebellion.

America was on the cusp of its own mass rebellion. He could hear it in the music on the radio and the pictures on the television and cinema screens.

But perhaps most pertinently in the poetry, where chaos and anarchy often find their home.

He felt he had already played some part in conducting and encouraging the oncoming zeitgeist, like a modern Prospero. He knew it wasn't just a figment of his imagination that day he left Welton. He'd seen it in his students' eyes, burning with the fires of protest from centuries past. Yes, he had thought about the power that goes with inspiring youths and rousing their hearts to fight the invisible war against the stifling traditions of academia and societal conservatism.

And naturally there would always be a sacrifice in the waging of that war.

Perhaps Neil was that most human sacrifice after all.

“There is a tide in the affairs of men

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

On such a full sea are we now afloat;

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.”

1960 began with a sense of renewal for Mr Keating.

It was a bright sunny morning in Berkeley, California and as he parked up in the university grounds, John took a moment to collect his thoughts.

A new beginning for him was like opening a brand new notebook where the possibilities for the future remained endless until that first commitment of the pen to the page and the path of destiny was set in motion.

Turning on the car radio, Brahms 2nd piano concerto was just beginning and John felt as if it was a good omen. Perhaps the overwrought Ludwig Van years were finally behind him now and the mellowness of Brahms would serve him better. He was entering middle age but still felt twenty one in so many ways. Nevertheless, he would try his best to avoid drama where he could. He hated the thought that he would become a cliche like one of those angst-ridden protagonists from a two bit pulp novel or one of those James Jones' melodramas.

No. He would aspire to live his life like a great poem by Whitman and grow into his maturity as a man and as a teacher with clear thinking so that he could lead the youth of today toward a brighter future.

A future where rebellion was not punished.