ONCE UPON A TIME IN VIENNA

“Am I sure? Only as sure as I am that the reality of one night, let alone that of a whole lifetime, can ever be the whole truth.” - Arthur Schnitzler's Traumnovelle

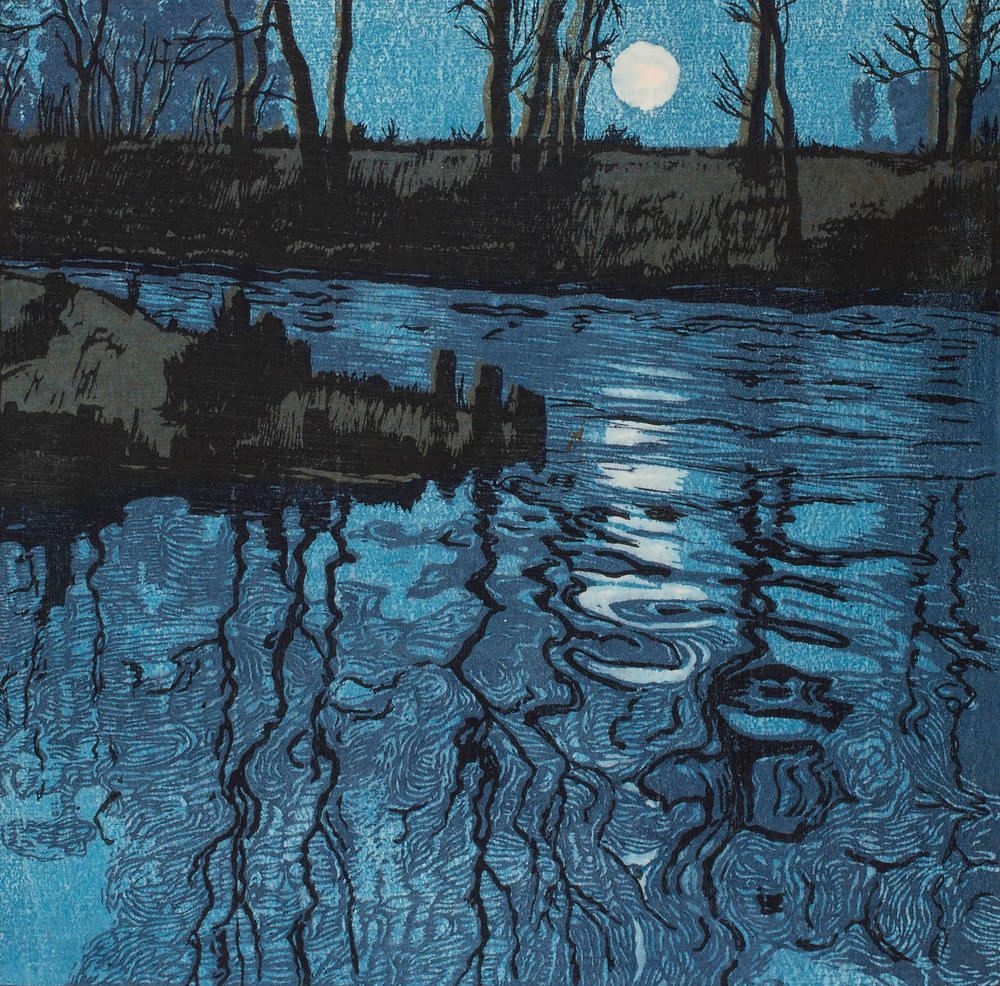

I would often take great pleasure walking through the Wienerwald at night, the silver moon filtering through the trees like a zoetrope. It would give me time to saturate myself in the atmosphere of the place before returning to the hustle and bustle of city life by early dawn.

The profound darkness of the woods made me feel especially alive. I would become aware of every sound around me, taking in all sentient presence from the fallow deer to the Ural owl.

As the night wore on the rushing sound of the Schwechat river gave me pause for reflection as I dipped my hand into the water to make sure I hadn’t become a ghost, so supernatural did I feel, alone, drifting through history.

Soon after, I could see the distant lights of the city ahead of me, like golden pearls. I felt as if I had emerged from some primordial state of being into civilisation.

That transition from the dark night to first morning light was such a heightened sensory thrill for me, I felt no tiredness whatsoever from my nocturnal trek.

I enjoyed very much observing the contrast between nature and man’s own constructed designs which were currently undergoing a creative revolution in Wien.

The year was 1908 and I had been visiting Vienna often lately for research. My German was more than satisfactory but I mostly enjoyed keeping myself to myself, watching people and events play out from a distance. I’ve always felt the writer is part spy, part voyeur and the current fascination for me was watching the city at a time of significant change in the early part of the 20th century.

I had rented a small apartment in Leopoldstadt and upon my return to my bed, I slept the entire day before resurfacing late afternoon and having some cake, coffee then wine in Cafe Sperl where I would make notes and watch the regulars converse amongst themselves. Revolutionary plots, romantic despair, musical arguments, I had the entire engine room of Western civilisation sitting around me and I loved every minute of it. I won’t pretend there wasn’t also a sense of sadness that came with it all, though. A tangible foreboding permeated the streets and coffee houses and though it suited the mood of my planned novel, I could see the toll it was taking on many of the good ordinary people of Vienna.

The city was tense and I could feel the often lamented golden age slowly ebbing away. And yet, I had the luxury of affording a certain amount of dispassion being essentially a tourist here.

An unconventional tourist it must be said.

There was a cauldron of confluence taking place here in Vienna at this time with all sorts of visionaries competing in art, politics and science. I’ve often wondered why the human race is unable to pause itself at certain junctures and slow down to enjoy its achievements. But perhaps it’s this inevitable propulsion of innovation and destruction that keeps the whole human theatre rolling along. If I was to choose a preferred medium for advancement then it would be music, enjoying the endless conversation between the past and and present composers in their bid for immortality.

I was sad to hear that Mahler had just left the city due to the increasing anti-Semitism that was growing. I was still haunted by his 6th symphony which I had attended the premiere of in Essen, Germany. It made such an impression on me that I had terrible dreams for weeks afterwards and felt as if my mind had been overtaken by the composer himself. To even recall the andante now reduces me to tears. I remember an old girlfriend of mine telling me how she might leave me if I continued to play Mahler around her. Needless to say, Mahler won that war.

This city of Mozart, Beethoven and Strauss waltzes had become an altogether darker place, both tonally and politically. I felt an urge to intervene somehow at the inevitable trajectory it was taking, but alas could do nothing. I was impotent as we all were at reversing the tide of events in human history.

“Excuse me sir? Would you mind if I sat at your table? It’s getting very crowded.”

The young man with gaunt features looked in a pitiful state and I was only too happy to accommodate him.

As he clutched his beer stein close to him I enquired as to what he was drinking.

“Water. I like to be sober when everyone else is drunk.”

I nodded in a sort of approval although I could see the young man piously observing my choice of beverage which happened to be wine.

“Please don’t judge me. I’m already half cut.”

“I’m sure you’ll end up telling me all your secrets and in the morning I’ll have power over you where you won’t even remember this conversation.”

“Or indeed your name.”

“I’m afraid I don’t give my name to strangers unless I’m sure they can be fully trusted.”

For the first time in our exchange I noticed a slight smile forming from the side of his mouth.

I changed subject as I felt he was enjoying undermining my attempts at engagement a little too much.

“Are you local?” I asked him.

“Linz.”

“Country boy eh?”

The young man appeared to not like this framing of mine, as if to say you’re nothing more that a bourgeois urban dweller, which was true, I must confess.

“Well, I came to Vienna to be impressed. But alas, I’m more depressed than impressed.”

I nodded again, though I wasn’t quite sure why.

“Give it time. Maybe it will grow on you.”

“Time is running out. The world moves fast.”

As much as I tried, I found the young man to be socially awkward and difficult to persuade toward a more optimistic view of the city; at the same time I was mindful that I was only here in the first place because I had already fallen in love with Vienna from all my reading about it.

I got up from the table and made one last attempt to engage the scrawny, haunted looking man.

“If you want my advice.”

“I don’t.”

I ignored his snappy negation of my offer and proceeded with my suggestion anyway.

“Find a nice girl to dance with.”

I can’t quite describe the look that was returned to me except to say it was somewhere between incredulity and disdain.

Smiling, I left him to stew silently in his own company.

Afterwards, I took my own advice which he’d refused and went to a nearby dance hall.

The familiar sound of Lehar’s overture to The Merry Widow had me eager to find someone to dance with but everywhere I turned, I found everyone except myself had a partner.

I ventured to the American style bar where I ordered an ostentatious cocktail.

Watching the gaiety and frivolity swirling and twirling all around me, I almost forgot the further troubles ahead for the city and indeed the entire century and felt momentarily convinced the golden age was going nowhere at all.

And to vindicate this feeling of optimism, I finally found a partner with whom to share the last dance and as we waltzed toward midnight, I felt dizzy from the joy, until, like Cinderella, I found myself, sober, back on the street, lost in time.

I fell asleep in Vienna but woke up back home in London. I removed the hi-tech lucid mask from around my head and took a shower that helped to wake me up fully from my trip.

Unlike air travel, simulated time travel had very few side effects, except for occassional bouts of melancholy from the extreme contrasts of history the witness experiences.

I gave myself a day or so to transition back into modern life before beginning my novel which now, after several experiences of old Vienna, I had even greater impetus to write.

How to begin, I wondered aloud to myself?

I made some fresh coffee and put some Mahler on through the stereo, then closed my eyes to recall the city of my lucid dreams.

And then it came to me, as simple as a fairytale and as graceful as a waltz.

“Once upon a time in Vienna”