THE LORD OF THE RE-WRITES

The next day they got back to the Shire and they went into a shed and Saruman came in.

He went away.

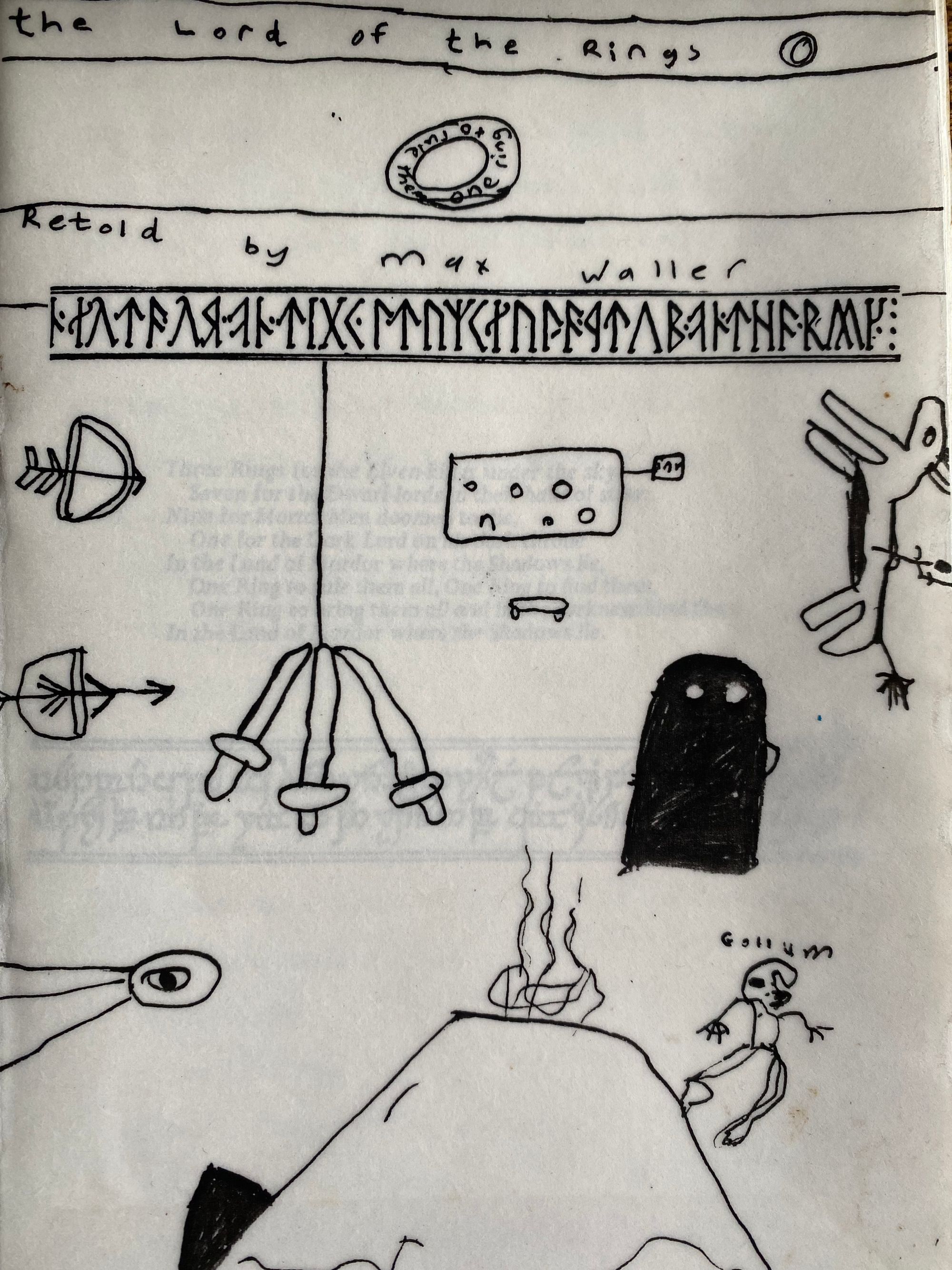

Comparisons are apparently odious, but as the world's oldest child prodigy I think I'm in a position to make this particular one. Mozart composed his first piano concerto at the age of four, and I re-wrote an abridged version of J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings at the age of seven. Although I'm sure Mozart's artistic talents were flying even higher by the time he was seven, in the context of the cultural wasteland that was the 1980's my achievement can be counted as comparably significant and historic.

I can't even remember what compelled me to do it, except for a confluence of egotism, precociousness and blatant plagiarism.

But perhaps, like the ring of great power itself, it may have brought a curse ("Bagginses!") on my life as it cemented unrealistic expectations of my innate genius which were possibly overestimated by my adoring, if somewhat biased, supporters.

So impressed were the teachers at my junior school, that they would allow me to write stories during maths lessons, subsequently resulting in me becoming irrevocably awful at the subject and possibly instilling a pathological fear of numbers ever since.

It was strange to have teachers leave you all alone to work in quiet away from your classmates, but perhaps they thought I might eventually credit them with helping my prolific talent to emerge on the global stage, thus ensuring the school's legacy for all eternity.

However, with great art comes the great weight of responsibility and as I scraped the marrow out of Tolkein's Magnum Opus, I felt blessed with genius by proxy of the old professor. I was essentially siphoning off all that he'd written and bastardising it so that my fellow seven year olds could understand the story better.

"Where is the one ring?"

"I'm not telling you Saruman."

"Then I shall look you up."

"Saruman. One day you shall die."

One thing old J.R.R. might have learnt from seven year old me was perhaps a greater sense of economy. Somehow, I had the unique ability to whittle entire chapters down to a few pithy lines, making sure at all times to keep the original story intact, if in somewhat cruder fashion.

Take, for example, this early crucial scene between the wizard Gandalf and the hobbit Bilbo in what is originally a fairly long drawn out scene of Tolkien-esque exposition. Then marvel at the sheer audacity of my brevity in reducing it to its essence.

"Well Bilbo. Are you still keeping the ring?"

"Yes. Why would you want to know?"

"You've got to give it to Frodo."

"Oh alright."

It makes you wonder if the original book might not have gained yet further global appeal if it had simplified these parts such as I had done as a child.

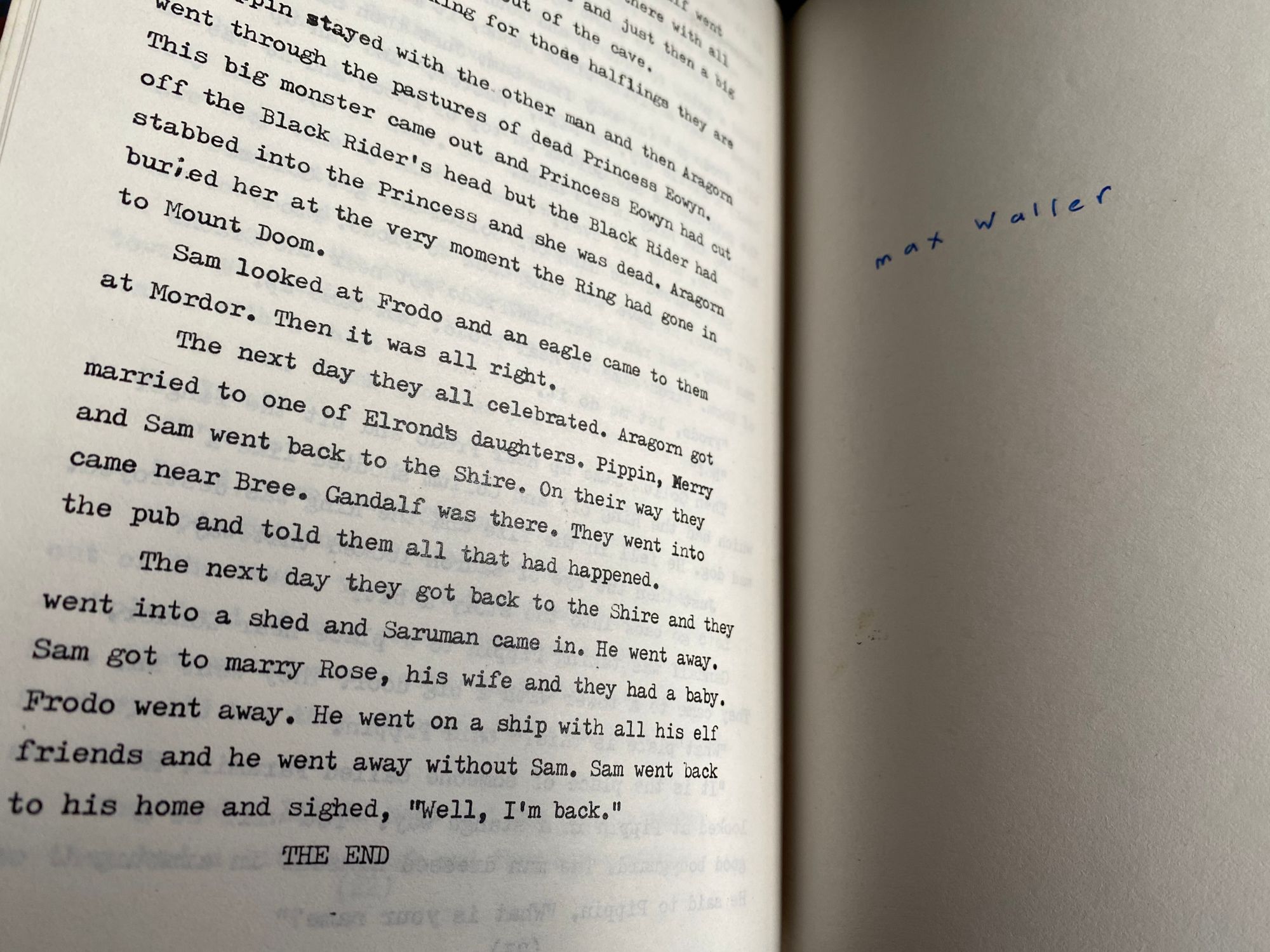

First handwritten then typed up from my work in rough, I developed my very own printing press, eager to share my work with the world.

Having illustrated the original printed copies of my abridged adaptation, I then set about handing them out to my fellow class mates at school. For those less close to me, I charged a whopping 5p per copy. But what value they got in return. Three volumes of dense middle earthness packed into a skimpy 24 page booklet. I can only imagine if I had applied the same treatment to Shakespeare, Dickens, Tolstoy and Proust, I might have reduced the entire Western canon to under a thousand pages in total.

Alas, it was not meant to be. Exhausted by my colossal efforts in reduction I confess I rested on my literary laurels for a few years (some says decades) afterwards.

Was this then my greatest achievement? It's quite possible. It was a moment of rare, focused, laser-like industry and one that invited others to hail me as a special talent.

Looking back I can say without question, I was special alright.

"Sam looked at Frodo and an eagle came to them at Mordor. Then it was alright."