BETWEEN TIME

There's a beautiful clip doing the rounds amongst the internet's film community lately of director David Lynch watching the ending of Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life with a sincere, childlike and teary-eyed reaction to the pure emotion at the heart of its message. It's perhaps especially moving because it was almost a year ago that we lost this "Jimmy Stewart from Mars" genius, and there's just that wistful sense that maybe, in some way, with the intervention of an angel or two, we might have been able to bring David Lynch back into our collective timeline somehow.

But maybe the director would object to monkeying around with any timelines in such a way just to assuage our insecurity about death and loss, when he's ever present in our hearts and minds every time we watch his work, just like he's here watching the masterpiece film by one of his creative predecessors, Frank Capra.

Both men appeared to investigate both the light and the dark of Americana, and it makes sense that there might be some synergy beyond the fact that Lynch looks and sounds a lot like Capra's favorite leading man, James Stewart. By the time Stewart was cast in It's a Wonderful Life, he had served as a combat pilot in WWII, and his own mortality no doubt weighed on his mind, which might explain why he is so utterly convincing in the famous bar scene, where George Bailey, in his darkest hour, prays to God for help.

Re-watching the 1946 Christmas film myself this evening, it suddenly struck me how the influence of It's a Wonderful Life just may have played a part in influencing the almost anti-Capra and horror-filled message at the very end of Twin Peaks: The Return (otherwise known as Season 3), where the nightmarish notion that we may never be able to return home to our family and our home once we've slipped between the net of reality and dream is explored, and how that quintessential sense of equilibrium may become lost forever if we try and interfere with time, space, and reality.

George Bailey's timeline of reality as he knew it is temporarily altered by the intervention of an amiable angel called Clarence Odbody who seems to have a handle on the time, space metric in accordance with Heaven's laws. Laura Palmer's timeline of reality is permanently altered by FBI Agent Cooper, who has attempted (much like Orpheus with Eurydice) to bring her back from an underworld of sorts to the town of Twin Peaks, only to find, when she gets there, that the house she grew up in and the year she is now in may be irrevocably altered.

Regardless of Agent Cooper's well-intentioned desire to resolve some type of equilibrium for the now un-murdered victim, Laura Palmer, he ends up in that pursuit becoming even more dissociated from any real, recognisable reality that she, or even he, can now comprehend.

Thankfully, George Bailey returns to Bedford Falls (after being given a glimpse of a life in which he hadn't existed in the town) and returns home to his wife and children with a newfound appreciation of his own value and place in the universe.

Of course, this time between Christmas and the New Year also offers a strange bardo of sorts, a semi-indeterminate period of days before we begin a new cycle. Here's hoping we approach this with gratitude, like George Bailey, and not fear, like Laura Palmer.

On a less serious note, I had a flashback of sorts watching It's a Wonderful Life earlier, and it was a memory of the first time I watched the film. Funnily enough, it was at the height of summer, and I was staying over at my friend's very modern house (similar to Cameron Fry's dad's house in Ferris Bueller's Day Off), where a lot of the tech accessories and furnishings wouldn't have seemed out of place in Patrick Bateman's apartment. This was a post-yuppie, mid-90s place in a quiet village in the Cotswolds that possessed a type of eerie, lonely atmosphere which felt transferred, almost teleported, from New York or London.

Watching Capra's It's a Wonderful Life seemed somehow anomalous in such a setting, though I appreciated the VHS projector and pull-down screen, the Bang & Olufsen speakers, and the white leather recliners where we could put our feet up in the early hours of the morning. There was an almost science-fiction feeling in watching the film in this quiet place, where you could almost believe that the world outside the house no longer existed and that we were the only two people alive in our De Sede–furnished spaceship, watching old classic Hollywood movies. Time seemed frozen until the film finally ended, leaving us suspended, caught in that strange space between time.

By the end of the movie, I can only say the sterile place seemed infused with a warmth and atmosphere previously denied to it, and we were exhilarated by the fairytale story of George Bailey and Bedford Falls as if it were an extension of our own town and lives. Little was I to know how much more powerful the film's message would be decades later, as I found myself becoming increasingly George Bailey-like.

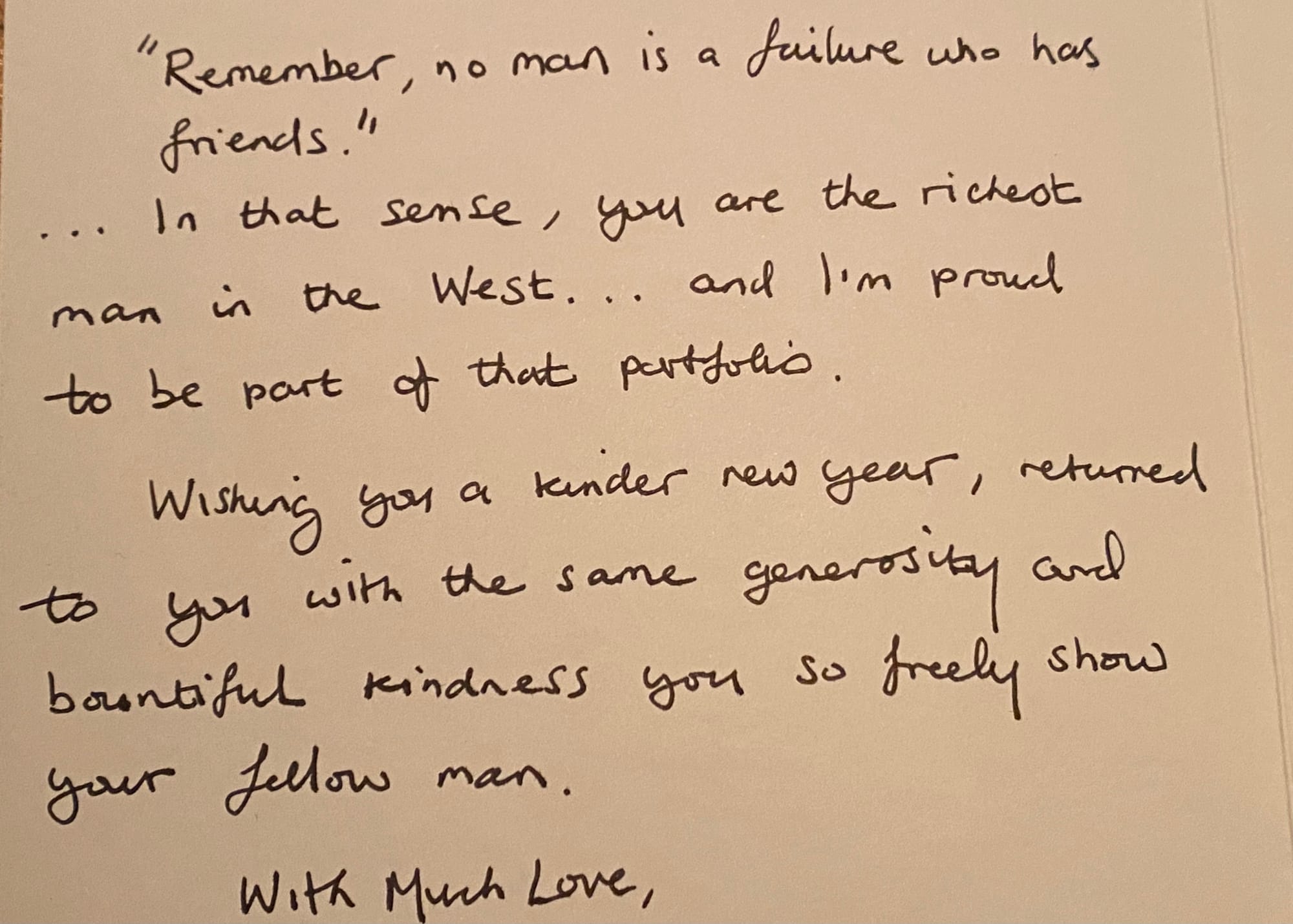

I wouldn't have personally made the comparison (feeling nothing like as important or value-filled as George in my achievements), but a close friend wrote a rather touching Christmas card message to me the other day and seemed to make the comparison more easily.

Thinking about it now, perhaps he's my guardian angel.

Maybe I'll stick with this current timeline while the compliments are this good.