PULP AMBITION

Sometimes I think that if I had the ability to write any type of novel, it wouldn’t be anything as epic or profound as Dickens’ Great Expectations or Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, but more like the kind of quality pulp fiction with mass appeal you’d find in a seaside holiday cottage, where the briny salt in the air mingles with the faded vanilla-and-coffee scent of sun-warmed pages. There’s something tantalising about those well-thumbed paperbacks you find in such places (often alongside old board games like Cluedo and Mastermind, with pieces long since lost); in a way, they make you appreciate how these mostly disposable books had seen so much use. How many hands had turned those pages, while each reader, over time, shared in the same excitement at the propulsive, addictively compelling stories contained within?

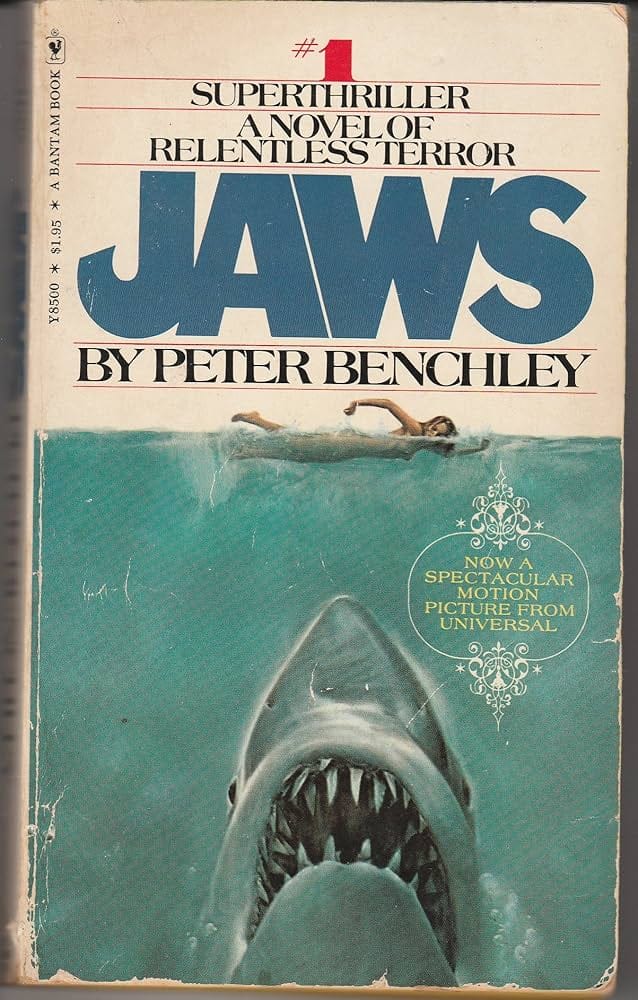

I can distinctly remember reading Jaws for the first time late at night, while a distant lighthouse flashed its beacon on the watery horizon, hearing the hum of coastal freight vessels in the distance, and wondering if a great white shark was on the prowl in the dark blue waters for some human flesh. It was a spine tingling reading experience.

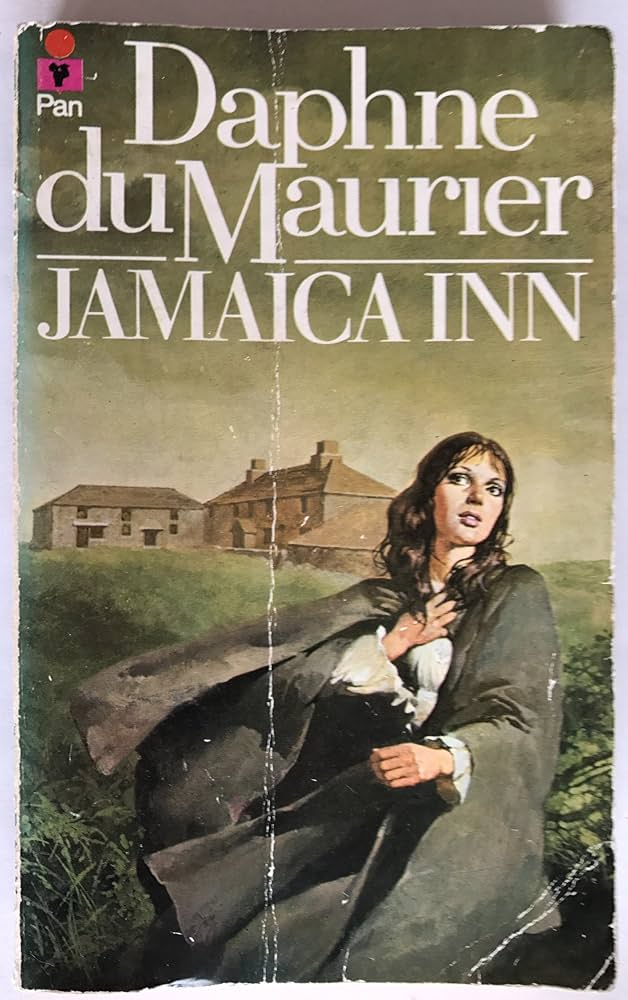

Of course, Peter Benchley’s Jaws and The Deep would be the high-water mark for this type of pulp in my “Seaside Holiday Cottage literary fetish.” I’d also include Puzo’s The Godfather and anything by Michael Crichton, Ira Levin, or Frederick Forsyth in that same company. Then again, I’d often find a du Maurier on the shelves, revamped with a sort of pulp-style cover—Jamaica Inn by way of Mills & Boon, with a glamorous-looking Mary Yellan running across a windswept Bodmin Moor. Perhaps more classics should have received this treatment. I can just imagine how many more people would have been hooked on the canon if the covers had been more tawdry—the democratisation of high culture through low-culture presentation.

Screenplay-wise, I’ve tried to sate my pulp ambitions a few times. The House at Black Lake was a cross between a Stephen King–style haunted house thriller and a dash of Peter Benchley. And while I may have overindulged my trashier instincts, it might still be ripe for novelisation—even if the film never got made (thanks, PM!). I’ve often wondered what it must be like to write a novelisation of a film and whether one can find inspiration in the process. Of course, I assume it’s primarily a money gig, but somewhere along the way, a writer surely has to find a way to make it enjoyable.

Quentin Tarantino recently wrote an expanded novelisation of his magnum opus Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, and I sense he had the same desire to replicate those airport and drugstore paperbacks from his past. Perhaps it’s the freedom from having to pretend to be highfalutin or profound that makes writing such things so tempting—the joy of simply engaging in the popcorn sensibility of escapism one remembers from childhood or adolescence.

And why is it that I can always hear a John Barry-style score accompanying these idle fantasies of mine while I daydream about them?