RISORGIMENTO

"If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change." - Tancredi

Pleasantly surprised by the quality of the new television series The Leopard (Netflix), which has had to contend with comparisons to the aristocratic perfection of the original Visconti movie starring Burt Lancaster, Alain Delon, and Claudia Cardinale, I am currently musing on 19th-century Italy—specifically the Risorgimento movement led by Garibaldi—and humming Verdi's "Va, pensiero" from his opera Nabucco.

It just so happens that I was recently reminded of an ancestor of mine, a portrait artist from Skipton named Richard Waller (1811–1882), who painted General Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1864. According to Piltdown_man on Rootschat.com: "Waller was one of seven painters who created a portrait of the General during his visit to Italy and, according to his obituary, 'Mr. Waller had the honour to be in the General's company during the whole of his stay.' Garibaldi even forwarded his robes to him and said, when it was completed, 'it was more to his taste than the others painted during his stay.'" This portrait appears to have been purchased by a Mr. McAlmont at the York Exhibition at the time.

In Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa's iconic novel The Leopard, the nephew of Prince Fabrizio Salina, Tancredi Falconeri, joins Garibaldi’s Redshirts during the Expedition of the Thousand, a crucial military campaign in the Italian unification movement (the Risorgimento). His motive for doing so stems more from youthful ambition than from any firm ideological devotion to the cause, though his pragmatism regarding the revolution sweeping through Italy clearly contrasts with that of his more fearful uncle, who resists the encroachment of Garibaldi’s plebiscite on his Sicilian aristocratic way of life.

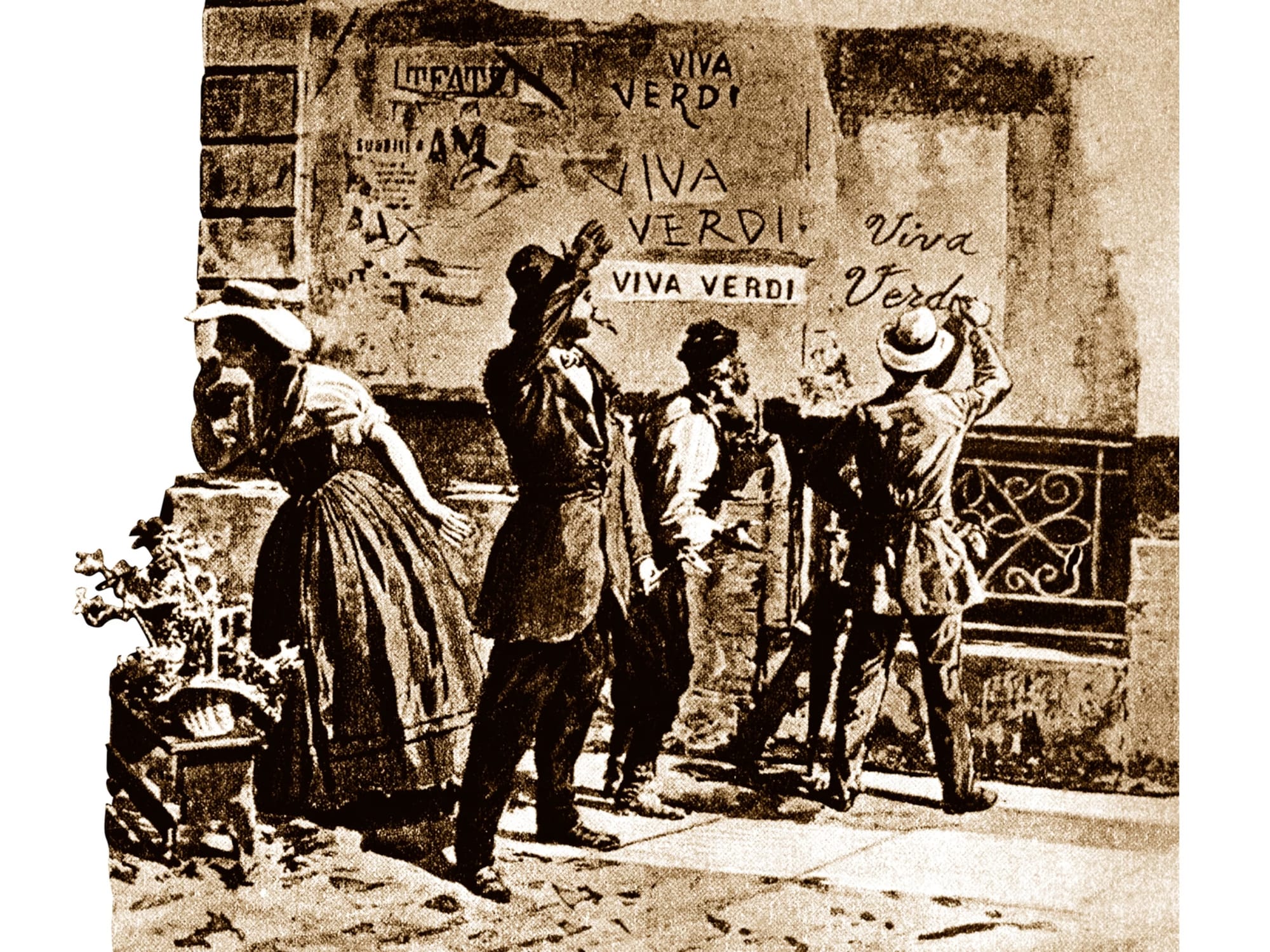

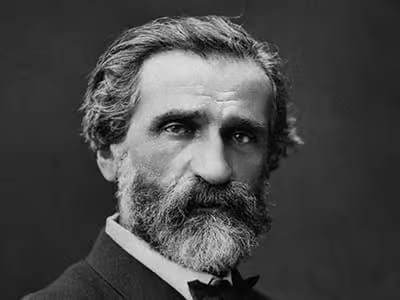

The opera composer Giuseppe Verdi became a cultural icon of the Risorgimento, even though his political involvement was more symbolic than active. His name was famously linked to the unification movement through the acronym 'Viva V.E.R.D.I.,' which stood for 'Viva Vittorio Emanuele Re D’Italia' (Long live Victor Emmanuel, King of Italy), referring to the future monarch who would help unify the nation. However, it was his much-beloved 'Va, pensiero' that truly amplified this connection, securing Verdi’s status as a key voice of Italian identity.

"Va, pensiero," also known as the "Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves," from Giuseppe Verdi's opera Nabucco, was first performed in 1842. Its significance to Verdi and his relationship with Italy is tied to both his personal artistry and the broader cultural and political events of the time. For Verdi, "Va, pensiero" marked a turning point in his career. Before Nabucco, Verdi had faced devastating personal tragedy—losing his wife and two children—and professional struggles, nearly abandoning music altogether. Upon reading the libretto for Nabucco, written by Temistocle Solera, Verdi was immediately inspired to return to composing. The chorus, in particular, resonated with him emotionally and artistically. A hauntingly beautiful lament sung by the enslaved Hebrews in Babylon, yearning for their lost homeland, Verdi’s stirring music imbues it with a profound sense of longing and dignity, demonstrating his rare ability to blend melody with raw human emotion.

This powerful chorus became an unofficial hymn of resistance for Italy during the Risorgimento, reflecting the Italians' strong desire for unification. At the time, the country was fragmented into numerous states, many under foreign control—primarily controlled by the Austrian Empire. The chorus’s lyrics, which speak of a people mourning their subjugated homeland ("Oh, mia patria sì bella e perduta!"—"Oh, my country, so beautiful and lost!"), clearly struck a deep chord with many natives who saw parallels between the Hebrews' plight and their own oppression. Though Verdi didn’t originally intend it as a political anthem, audiences at the time interpreted it as a call for their own liberation and unity. Often during performances, they would weep and demand encores—proving that it had quickly become an adopted anthem for their cause.

After Verdi’s death in 1901, the chorus retained its power and significance. At his funeral, mourners spontaneously sang "Va, pensiero" as his procession passed by—a testament to its enduring link to both the composer and the defiant Italian spirit. Today, it remains one of Italy’s most cherished musical treasures, often proposed as a potential national anthem, reflecting Verdi’s lasting legacy as a unifier through his art.

As someone who loves all things Italian, my sympathies naturally align more with Verdi, Garibaldi, and the Risorgimento. However, I can't help but feel for poor Prince Fabrizio Salina—after all, he never had his portrait painted by a Waller.

Just this morning, I’ve been imagining a mash-up style movie concept (E.M. Forster meets di Lampedusa) in which a polite English portrait artist decides to take a holiday during a blazing revolution. Starring Hugh Grant as Richard Waller and Salvatore Esposito (from Gomorrah) as Garibaldi, I can already see an instant classic in the making.

Naturally, Verdi will provide the music.

VIVA!