STAMP DUTY

Terry meets Julie

Waterloo Station

Every Friday night

But I am so lazy

Don't want to wander

I stay at home at night

But I don't feel afraid

As long as I gaze on Waterloo sunset

I am in paradise

I'm not going to pretend I'm a connoisseur of actor Terence Stamp's movies outside of The Collector, Superman II, The Limey, and an obscure biopic based on Gurdjieff's Meetings With Remarkable Men. But I was, of course, aware of his iconic status as a symbol of 1960s London, thanks to his being referenced alongside Julie Christie in the Kinks’ masterpiece Waterloo Sunset—a song my dad, who belonged to the same Silent Generation as Stamp, first introduced me to.

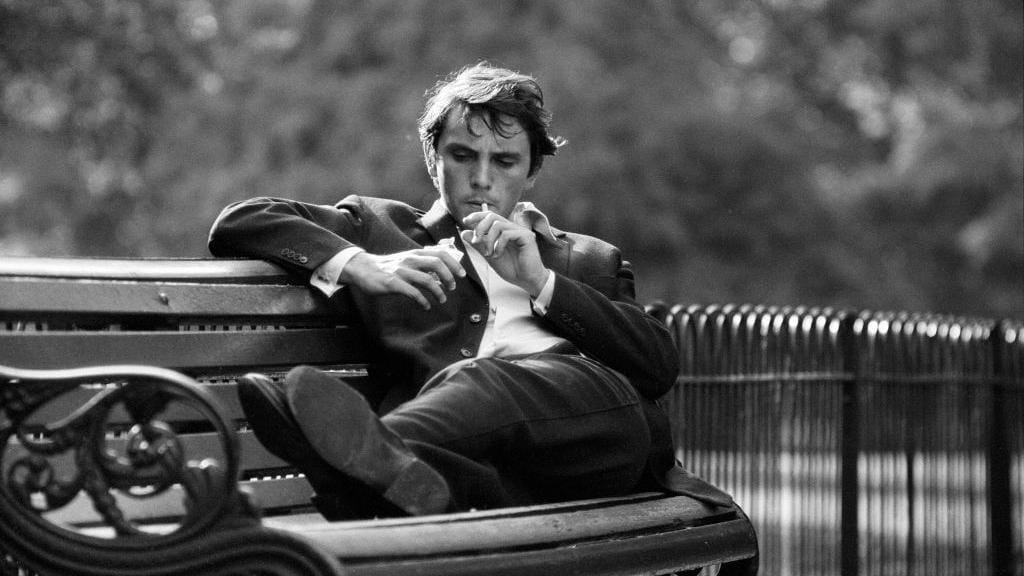

There was a kind of steely, rebellious individualism in Stamp's face that defines his look—like a man beyond the reach of the authorities because he is an authority unto himself. His eyes seemed to bore laser beams through passing souls, much like his on-screen villain General Zod in Superman II.

I particularly loved director Edgar Wright's tribute to Stamp on X, especially his reference to London’s greatest Irish bar, The Toucan—a place where I once nearly rendered myself unconscious (not because of the booze, but because of the low ceiling by the toilets).

I am deeply saddened by the passing of Terence Stamp, a British actor who was truly iconic. An East Ender that rose to such fame in Swinging Sixties London, he could rightly be called its epicentre. Terence’s career spanned seven decades and never stopped surprising. I was fortunate enough to work with him on what became his final screen role in Last Night in Soho.

Terence was kind, funny, and endlessly fascinating. I loved discussing music with him (his brother managed The Who, and he’s name-checked in The Kinks’ Waterloo Sunset) or reminiscing about his films, going back to his debut in Billy Budd. He spoke of his last shot in that film, describing a transcendental moment with the camera — a sense of becoming one with the lens.

Decades later, while directing him, I witnessed something similar. The closer the camera moved, the more hypnotic his presence became. In close-up, his unblinking gaze locked in so powerfully that the effect was extraordinary. Terence was a true movie star: the camera loved him, and he loved it right back.

If I have a regret, it’s that he had to endure a few night shoots — tough for an older actor. Yet this gave rise to an anecdote that lives on in Soho. In one scene, his character exits The Toucan pub via the basement stairs. It was late, and Terence — who never did many takes — looked at the setup and said: “This shot isn’t going to be in the movie.” I asked why. He deadpanned: “This staircase isn’t good enough to be in a movie.” It was one of the funniest things ever said to me on set. We did the shot and I promised it would make the cut.

Later, at a Q&A, I told this story when the Toucan’s owners were present and they immortalised his remark on a brass plaque that you can see at the top of those basement steps.

The last time I saw Terence, he was in excellent spirits. He came to record ADR and perhaps because of his prolific Italian film career, his looping was flawless. Afterwards, over tea, he regaled me with stories of Fellini, Pasolini, Wyler and Ustinov. I hugged him goodbye, but never saw him again.

You will be missed, Terry. But you are immortalised — in film, in song, in print and in the heart of the city where you were born.

Edgar Wright