FROZEN FRAMES

Though screenwriters aren’t often asked about their favourite shots in cinema, I thought I’d venture a selection of 13 beautiful images to remind myself that sometimes a picture really does speak a thousand words (a lesson worth remembering when writing a screenplay). Of course, being verbose like Aaron Sorkin can work on certain days, but films can’t live on words alone. After all, the form was born in silence, and the moving image was the spectacle that became the attraction.

13. The Tree Of Life (2011)

Terrence Malick frames the human subjects and cosmic phenomena of Earth and the wider universe in The Tree Of Life as if seen through the eyes of God—whether it be galaxies, stars, the viewpoint of new life on Earth, or the beauty of nature as well as the designs and creations offered in the honour of God.

The film, overall, feels a little creaky in how it attempts to handle its vast spiritual themes, but its cumulative effect through sound and image is undeniable.

Malick is perhaps one of the few modern directors who can capture scenes on film with the untarnished wonder of a child.

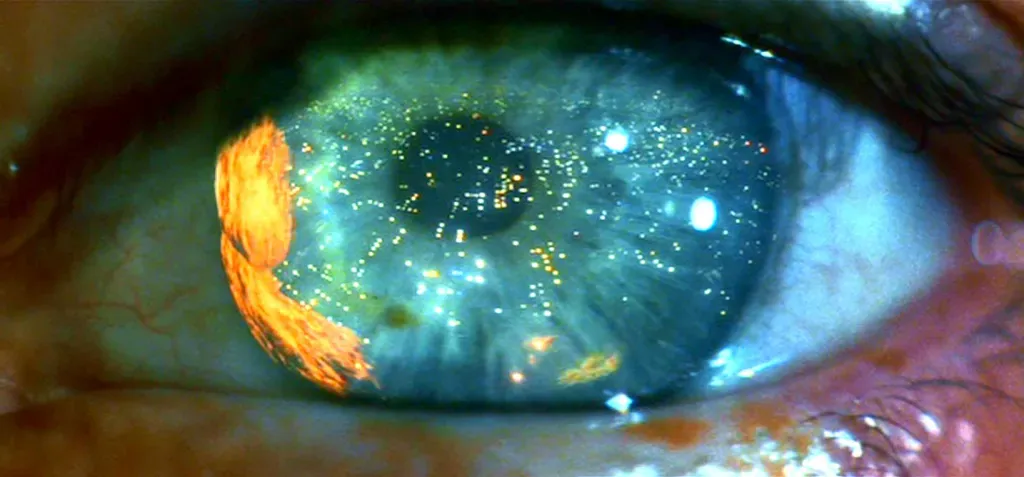

12. Blade Runner (1982)

Ridley Scott is of course one of the great visual stylists of cinema history and no where is his craft better demonstrated than in Blade Runner (1982) where the future is depicted as a confused society where humans and replicants (artificial humans) are indistinguishable from one another.

It is in his rendering of a futuristic Los Angeles that this uneasy atmosphere of sci-fi noir comes to life—through neon-soaked streets, digital advertising on massive and anonymous skyscrapers, and in the reflections of irises we cannot quite determine to be human or replicant.

And yet there is a nihilistic beauty to this bleak vision that is undeniable.

11. The Leopard (1963)

Every frame of Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard could be framed and hung on a wall, but perhaps the most subtle and beautiful image is that (early on) of the aristocratic Salina family attempting to pray, while the faintest breeze conveys the oppressive Sicilian heat and a barely perceptible sense of revolutionary change hangs in the air.

There is a nervousness within the sanctity of the scene that reaches the viewer—a result of masterful direction and perfect composition.

It sets the tone for a film that portrays an aristocracy running out of time, forced to adapt to the historic changes heralded by Garibaldi and his Red Shirts.

10. The Night Of The Hunter (1955)

Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter contains so many indelible fairytale/nightmare images within its relatively short running time, but perhaps my favourite is the scene of the two children, John and Pearl Cooper, hiding in a barn and watching the silhouetted figure of Robert Mitchum’s preacher riding his horse as he prowls the moonlit horizon.

The sense of framing is not dissimilar to John Ford’s legendary final shot in The Searchers, which uses the dark interior to frame the character and landscape beyond.

In both instances, it works beautifully.

9. The Naked Island (1960)

Nearly every frame of Kaneto Shindō's The Naked Island is stunning, and it is through its visual excellence and use of composition to tell a story that the film succeeds in its ambition as a wordless movie.

With shimmering cinematography by Kiyomi Kuroda, the film conveys through his lens the beauty, majesty, and tyranny of nature in relation to human lives—a single island family attempting to survive under difficult circumstances, yet humbly working in harmony with the challenging elements that surround them.

8. Paris, Texas (1984)

The reds, whites, and blues of Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas are a marvel, as are the Edward Hopper–like tinted greens and orange-red sodium city lights, which capture the mellow loneliness of a modern world where the protagonist, Travis (Harry Dean Stanton), can find no home.

Paris, Texas is pure Americana in cinematic form, and perhaps because he was European, Wenders was able to bring a freshness to the landscapes and cityscapes in a way that hadn’t been seen since the late, great John Ford and his classic Westerns.

This was America seen through both an idealised and partially detached lens, allowing for the most successful cinematic fusion of American and European sensibilities since Godard’s Contempt, which similarly used interiors and exteriors to frame its characters.

7. Fallen Angels (1995)

There’s something unique about Wong Kar Wai’s relationship with Hong Kong’s neon lights, where vampire-like nocturnal figures emerge to interact in seedy bars, fluorescent-lit takeaways, and wander the streets in search of love, retribution, and fast food.

The final image of Fallen Angels (a sequel to 1994’s Chungking Express) depicts a transient connection in a modern world moving toward increasing atomisation. It is perhaps one of the most beautifully romantic images of late 20th century cinema: Michelle Reis rides pillion on the eccentric, mute Ho Chi-mo’s motorcycle through the Cross-Harbour Tunnel as the first light of dawn breaks the artifical tunnel lighting, all while The Flying Pickets’ cover of Only You plays over the scene.

6. Bleu (1993)

The cool, swimming-pool blue tones of Kieslowski’s Bleu (the first part of his Three Colours trilogy) are the perfect choice for visually expressing the numbness of grief felt by Juliette Binoche’s character, Julie, who has lost her husband and daughter in a tragic car accident.

In particular, the scenes where Julie drifts in the symbolic womb of the pool—suspended in a bardo between life and death—demonstrate once again why Kieslowski was a master at aligning a character’s internal psychology with the environment they inhabit.

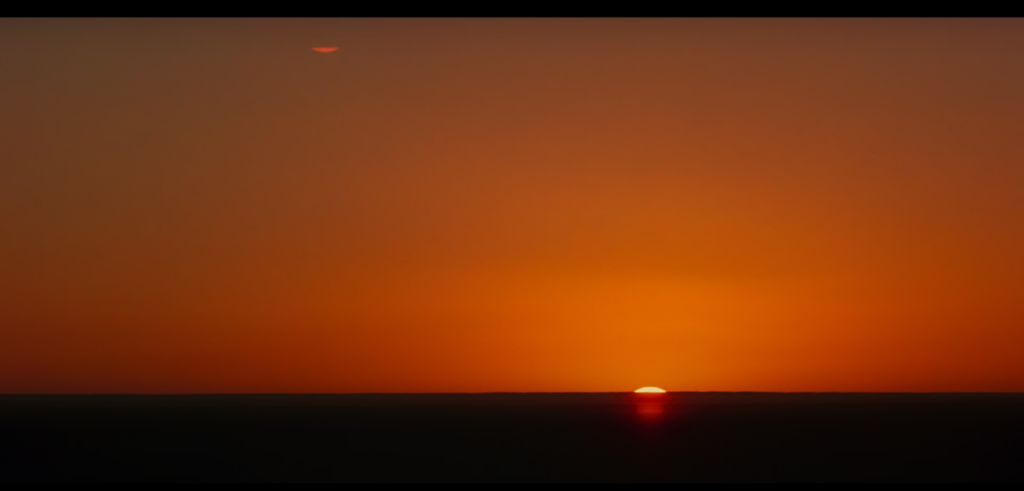

5. Lawrence Of Arabia (1962)

Eyes may roll at the predictable choice of David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia appearing in this cobbled-together list of mine, but although it’s not a film I return to often, I still get a thrill looking at individual frames that take the breath away more than sixty years after its original release.

There is a majesty to the grand compositions of the desert vistas from matchstick sunsets to star filled nights—the closest one can get to appreciating the Wadi Rum of Jordan without actually going there in person.

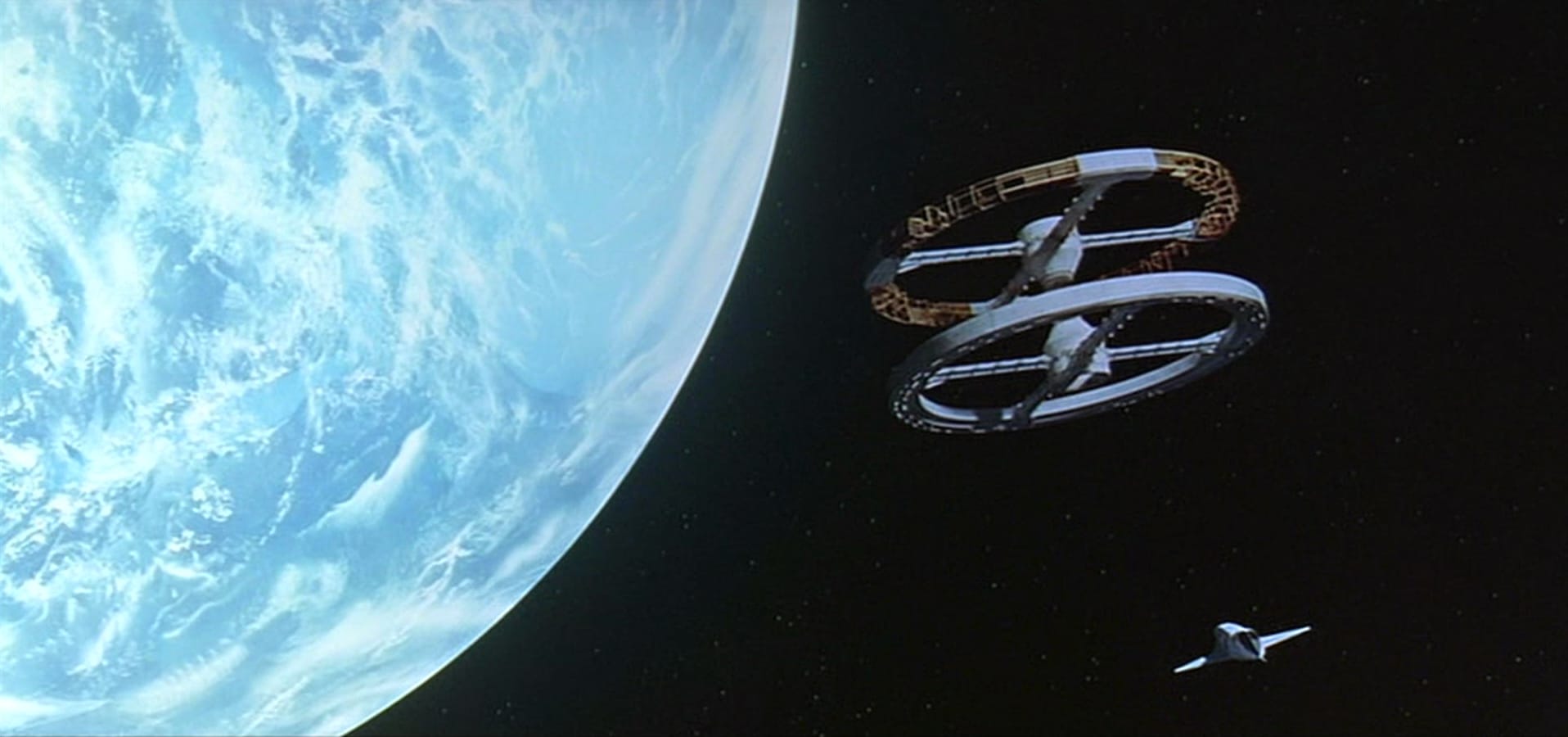

4. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Kubrick’s famous match cut from the dawn of man to the age of space exploration is iconic, and it is precisely this evolutionary leap—omitting the entire timeline of humanity’s development in between—that makes it so extraordinarily audacious.

We cut to the chase: an ape hurls a bone into the sky, which transforms into a spaceship approaching a rotating docking station above the Earth. As Strauss’s serene Blue Danube waltz accompanies the carousel-like movement, we find ourselves adjusting in a state of wonder, without questioning this monumentally cosmic time jump.

That Kubrick was able to create such a perfect visual conception of space before the famous moon landing of ’69 is nothing short of a feat of cinematic—and almost supernatural—genius.

3. The Age Of Innocence (1993)

Scorsese isn’t typically known for transcendent moments in cinema, often preferring to remain rooted in the blood and guts of the streets or among lowlifes, but in his screen adaptation of Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, he creates a stunning moment of romantic longing that ranks among the very best on screen.

Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis), engaged to Ellen (Winona Ryder) but secretly in love with Countess Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer), gazes at the woman he will never be able to openly love across the harbour, where sailboats drift along the sunset horizon. The distance between them perfectly encapsulates this impossibility and creates a memory he will recall toward the end of his life, when the regret of not acting on his love will haunt him forever.

2. A Room With A View (1985)

I think I can attribute much of my Anglo-Italian cultural sensibility to this Merchant Ivory masterpiece, and its exquisite poetic qualities are epitomised in the sublime shot of Lucy Honeychurch (Helena Bonham Carter) and George Emerson (Julian Sands) standing in a poppy field above the hills of Florence, accompanied by the sublime sounds of Puccini—an eternal moment that lasts only a few seconds before being rudely interrupted by Cousin Charlotte (Maggie Smith).

But while it lasts, it is truly celluoid heaven on earth.

1. Kaos (1984)

It takes a while to reach the single greatest shot in the Taviani brothers’ three-hour Sicilian epic Kaos, but when it arrives, it is truly worth the wait.

Watching young children slide down a mountain of white pumice into the foamy waves and, eventually, the turquoise sea is, for me, the most moving and transcendent image in all of cinema.

There is something sublime in the way the human figures interact with the landscape—as a symbol of the freedom and joy of childhood—while the preceding spectre of death (a sickly mother) back on the beach further heightens its sense of fleeting and precious beauty.