THE ATMOSPHERE OF MEMORY

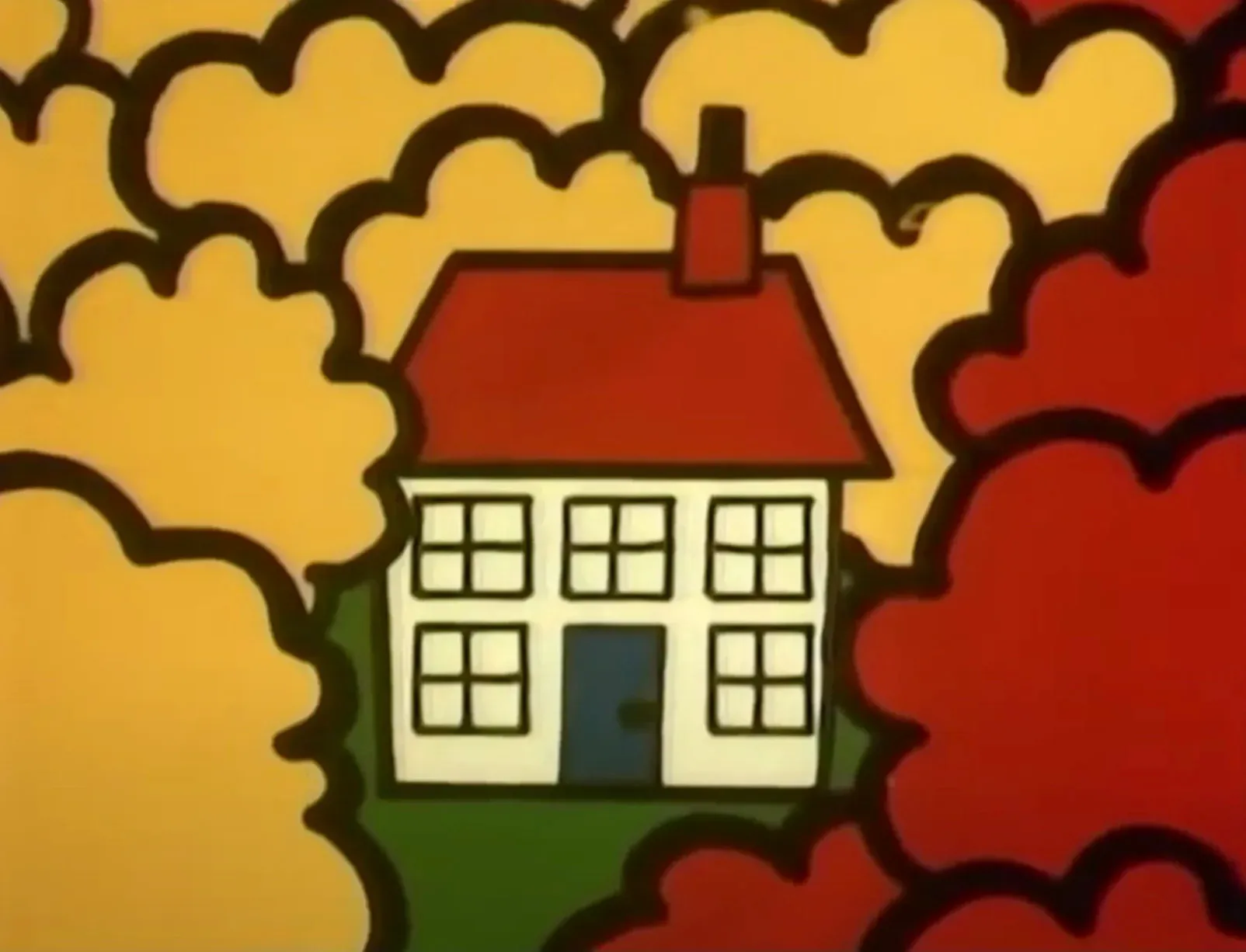

I am forever interested in how certain things prompt memories of our past without always seeming to have an obvious reason why they do. Mr Jelly's House in the woods, for example, from the Roger Hargreaves book 'Mr Jelly' always seems to remind me of several places I visited when I was a child, but which I can never seem to find again.

Though I have not unlocked seven volumes worth of memories from the single bite of a cake like the protagonist of Marcel Proust's 'In Search Of Lost Time', I have had one distinctly evocative recall from a fragment of music recently and I'm intrigued as to what exactly the correlation is between this composition and my own personal biography.

Maybe there isn't one.

I've been stubbornly persistent with Mahler's 7th Symphony over the decades. After only recently finally realising the greatness of the 8th Symphony (my one major highlight of the Covid years), it is now only the 7th I find myself less convinced of than all the other symphonies in Mahler's canon of ten. And even then, I doubt my doubt, knowing how greatness can sometimes emerge like a hidden 3d poster image in your perception of deceptively great works of art over time.

Without going into any great deal of musical exposition in an attempt to interpret the symphony and its meaning (beyond my pay grade,) I prefer right now to focus on just one small section about ten minutes into the 1st movement (Langsam -Allegro) of the symphony that for some reason has the mysterious affect of reminding me of an obscure atmospheric memory from my childhood growing up in Gloucestershire.

One thing that cannot be denied about Mahler is, just like Beethoven, his uncanny ability to begin a symphony.

And the 7th is no exception.

After an ominous opening section dominated by mysterious horns that transition into a sporadically psychotic tramping march which offers little pause for reflection, a brief hymn-like second subject opens up midway (around 10:00) through the 1st movement like a sunlit clearing in a dark wood. Nothing prior to this unexpected moment has signalled to the listener that such a flourishing of serene beauty would suddenly arrive at this juncture but that is perhaps why it creates such a magical effect - 'the moonlight's balmy waves' - in a movement that can be quite testing to both the initiated and uninitiated Mahler listener.

In this section, trumpets followed by spiky oboes and restless flutes herald a most welcome musical and unwordly quietude that leads to an old Hollywood sounding harp's cascade that invites the rest of the string section to further elaborate on this pastoral section, opening up into a shimmering wonderment of 'trilling winds and rocking string figures' that is both lush and peaceful.

Even the first time hearing it when I was a student at university I remember seeing the vague form of a bridge in my mind's eye from my not so distant past, a bridge that has since become blurred between my own memory of its reality and Renoir's 'Japanese Bridge' from his famous painting.

Listening to this sublime section more recently I now recall further details such as the greenish blue and silver thoraxes of dragonflies (Banded Demoiselle?) hovering across an eerily still canal in the midst of lazy summer heat next to a white and blue iron bridge that had seemingly had no other function than to look pretty.

Something about this picture in my mind creates a sense of complete and utter peace and perhaps a moment where I was utterly at one in my environment and a sense of totality was achieved without any conscious effort on my behalf. How much do we try as adults to get ourselves back to such a place of perfect peace as this? I know I do, a place where nature provides a momentary glimpse of heaven on earth and we succumb without any resistence whatsoever in belonging to it.

In Donald Mitchell's book 'Discovering Mahler, Writings On Mahler, 1955-2000', he notes how Mahler broke through a creative block in finishing the symphony:

"It wasn't, however, until the summer of the next year 1905 that in an extraordinary eruption of creativity he finished work on the Seventh. Fascinatingly, it was the trip across the lake, and specifically the rhythm of the oars, that in Mahler's own words in a letter to Alma - enabled him to overcome the block that had prevented him from finishing the symphony: 'I got into the boat to be rowed across. At the first stroke of the oars, the theme (or rather the rhythm and character) of the introduction to the first movement came into my head - and in four weeks the first, third, and fifth movements were done!'

Though I stood in front of a canal instead of a lake and observed dragon flies wings instead of the oars of a boat, I can see how the effect of all the elements created a moment of a cosmic epiphany for me as a young child, as if the universe revealed to itself in one perfect picture.

Listening to the point of near obsession to this second subject of the 1st movement of the 7th I wonder if perhaps it was the dissolving into nature that helped create this amazing music for Mahler.

All I know is that when I hear it now it helps unlock something inside of me.

Not just the memory.

The atmosphere of memory.