DON G

'Don Giovanni' is an opera that, 200 years later, we're still struggling to try to understand." - Peter Sellars

My first proper introduction to Mozart's Don Giovanni and the stage work of opera director Peter Sellars was Christmas 1989, when I was eleven years old, and his three ultra-modern Mozart/Da Ponte productions were aired on BBC2. It was a time when Regietheater (director's theater) was still a relatively new phenomenon, and feathers were being ruffled by upstarts like Sellars and David Alden, who were deconstructing repertoire opera with their own subversive interpretations.

But I wasn’t aware of that in any conscious way; I just found the modern staging combined with 200-year-old music to be visual and audio dynamite, and it seemed cool and punk to me somehow.

By switching the traditional European setting of Don Giovanni to a modern, urban American city (most likely intended to be New York), Sellars instantly provided an arresting backdrop that could simultaneously explore contemporary themes of wealth, privilege, and social inequality while also honoring the timeless themes of the original opera, including promiscuity, revenge, fidelity, and honor. Having scenes play out in dingy apartments, seedy motels, and fast-food restaurants, the 1980s audience (including, no doubt, a considerable number of Trading Places-style yuppies) would have seen a reflection of the other side of society’s coin—the side that would typically not find itself in an opera house.

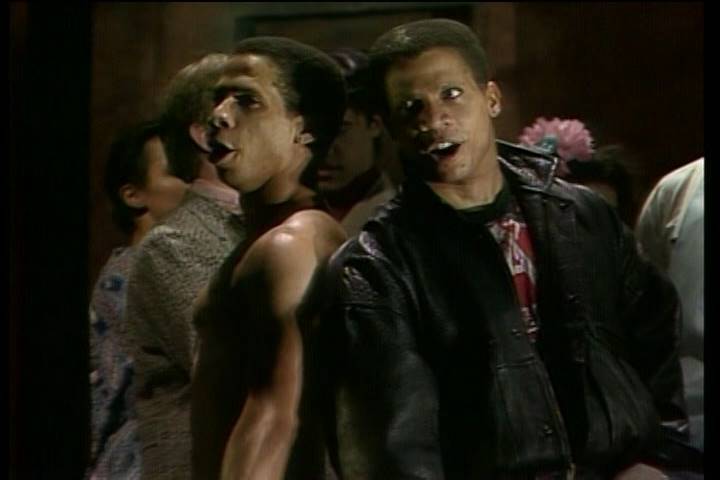

Casting two African American twins to play Don Giovanni (Eugene Perry) and Leporello (Herbert Perry) was genius, as they could interchange and deceive the characters in the opera even more plausibly than usual. With a greater emphasis on the predatory nature of sexual violence, the dance between desire and danger for both the libertine anti-hero and the women he seduces and rapes was brought far more to the forefront than traditional productions had managed. This was more akin to Bret Easton Ellis American Psycho territory in its psychological darkness and social commentary than the more quaint Otto Shenk ‘chocolate box‘ European-style productions.

The three central women characters—Donna Anna, Donna Elvira, and Zerlina—were also portrayed as more assertive than usual, making the sexual politics of the piece more interesting and highlighting feminist concerns of the era in which the opera had been provocatively recontextualised. Having Donna Anna’s fiancé, Don Ottavio, as a strung out heroin addict also highlighted the drug issue in modern America, as well as the ever-present fear of AIDS.

Certainly, to my young mind, I could never perceive opera as stuffy, uncool, or beyond reaching out to wider audiences after watching this electrifying interpretation, which no doubt helped to significantly change attitudes toward the benefits of updating repertoire works from the opera canon with more modern settings.