RESURRECTION AND MAHLER'S 2ND SYMPHONY

Sometimes with classical music I like to think I exist in that happy medium, somewhere between Morgan Freeman's character Red in The Shawshank Redemption ("I have no idea to this day what those two Italian ladies were singing about") and the florid style of legendary music critic Neville Cardus, though I fear it's more the former than the latter. Basically, I need just enough space to allow my heart and mind to interpret intuitively and freely without being tied down to a literal analysis of any one piece.

The first time I was made aware of Mahler's monumental 2nd Symphony, "The Resurrection", was when watching a Leonard Bernstein Mahler documentary called 'The Little Drummer Boy' which I still cherish and return to often. It may be sacrilege to say this (are you listening Mr Hurwitz?) but I've come to feel that Bernstein was better as a teacher than as a conductor of Mahler and one who successfully initiated me into the world of the composer which is testament to his exceptional oratory.

In the Drummer Boy documentary, Lenny leans over a piano, shirt unbuttoned, with a backdrop of a swarming beach in Tel Aviv behind him. He has the appearance of a more handsome, and considerably more sweaty, Hyman Roth from The Godfather Part 2 as he deconstructs the re-occuring motif of the little drummer boy as a persistent symbol/spectre of death throughout Mahler's 9 symphonies. I remember borrowing the video lecture from my film university library and watching it back on my TV/Video combo set in the room I was renting in Trebor Avenue late one night in April. The sound of blackbird song outside my window accompanied the timpani and strident brass of Bernstein's orchestra blasting Mahler's music in what appeared to be cathedral like spaces.

As a music lover, it was evident, as with other titans of Western music such as Bach, Beethoven and Wagner, there could be no escaping the sheer collosal scale of Mahler. Though he would compose more initimate works like the 4th and possibly the 7th, the rest of his symphonic canon consists of gigantic mountains of music that must be climbed like Everest, Denali and Aconcagua or else you find yourself in the foothills of doubt and regret, destined to forever wonder what lies in the high peaks of Mahler's genius compositions.

I remember being at a concert at the Albert Hall once with some Chinese friends of mine and one young woman from the group told me she had to leave her boyfriend because he was listening to too much Mahler. This piqued my interest instantly and I would only later learn through my own immersion into the subject what the nature of his obsession was by listening to the music myself.

Being forced to choose between listening to Mahler or maintaining a relationship is a dilemma I would prefer not to have to face. I like to believe I have enough powers of persuasion to convince even the most sceptical of people that listening to Mahler symphonies is an essential rite of passage that should be experienced at least once across the span of a human life.

But would I start with the 2nd Symphony by way of introduction? Probably not. Even to this day, even knowing how intense and epic other symphonies by the composer are, I still feel the Resurrection symphony is possibly the biggest in terms of sheer conceptual scale, though the 8th might have something to say about it.

The way I feel about the 2nd symphony is that it is like a far bigger version of the 1st 'The Titan' and by that I mean off the scale big, like comparing a raging mountain river to a seismic tsnumai that has arisen from the earth's core.

To give you a sheer sense of its size in terms of thematic design, here are the composer's accompanying notes for a performance of the symphony in Dresden in the year 1901.

First Movement: Allegro maestoso

“We are standing near the grave of a well loved man. His whole life, his struggles, his sufferings and his accomplishments on earth pass before us. And now, in this solemn and deeply stirring moment, when the confusion and distractions of everyday life are lifted like a hood from our eyes, a voice of awe-inspiring solemnity chills our heart, a voice that, blinded by the mirage of everyday life, we usually ignore: “What next?” it says. “What is life and what is death? Will we live on eternally? Is it all an empty dream or do our life and death have a meaning?” And we must answer this question, if we are to go on living. The next three movements are conceived as intermezzi.

Second Movement: Andante

"A blissful moment in the dear departed’s life and a sad recollection of his youth and lost innocence."

Third Movement: Scherzo

A spirit of disbelief and negation has seized him. He is bewildered by the bustle of appearances and he loses his perception of childhood and the profound strength that love alone can give. He despairs both of himself and of God. The world and life begin to seem unreal. Utter disgust for every form of existence and evolution seizes him in an iron grasp, torments him until he utters a cry of despair.

Fourth Movement: Alto solo. ‘Urlicht’ (Primeval Light) – from the Knaben Wunderhorn

The stirring words of simple faith sound in his ears: “I come from God and I will return to God!”

Fifth Movement: Aufersteh'n

Once more we must confront terrifying questions, and the atmosphere is the same as at the end of the third movement. The voice of the Caller is heard. The end of every living thing has come, the last judgment is at hand and the horror of the day of days has come upon us. The earth trembles, the graves burst open, the dead arise and march forth in endless procession. The great and the small of this earth, the kings and the beggars, the just and the godless all press forward. The cry for mercy and forgiveness sounds fearful in our ears. The wailing becomes gradually more terrible. Our senses desert us, all consciousness dies as the Eternal Judge approaches. The last trump sounds; the trumpets of the Apocalypse ring out. In the eerie silence that follows, we can just barely make out a distant nightingale, a last tremulous echo of earthly life. The gentle sound of a chorus of saints and heavenly hosts is then heard: “Rise again, yes, rise again thou wilt!” Then God in all His glory comes into sight. A wondrous light strikes us to the heart. All is quiet and blissful. Lo and behold: there is no judgment, no sinners, no just men, no great and no small; there is no punishment and no reward. A feeling of overwhelming love fills us with blissful knowledge and illuminates our existence.”

Yeah, this isn't one to drive to the shops to, unless you're planning a road trip like David Hockney used to do through the Malibu Canyon and the Santa Monica and San Gabriel mountains at sunset and sunrise listening to Wagner's Parsifal, Tristan and Das Rheingold.

In fact this isn't at all a piece of music you can multi-task to unless you eliminate movements 1 and 5 which would defeat the whole point. This is a work of such magnitude and awe inspiring grandiosity that it demands of its listener total devotion and perhaps no-one should be expected to make that type of commitment in an age where time is dictated by how many things we can consume in a day and not how few.

Mahler's 2nd is a work that you really need to take the entire day off to appreciate.

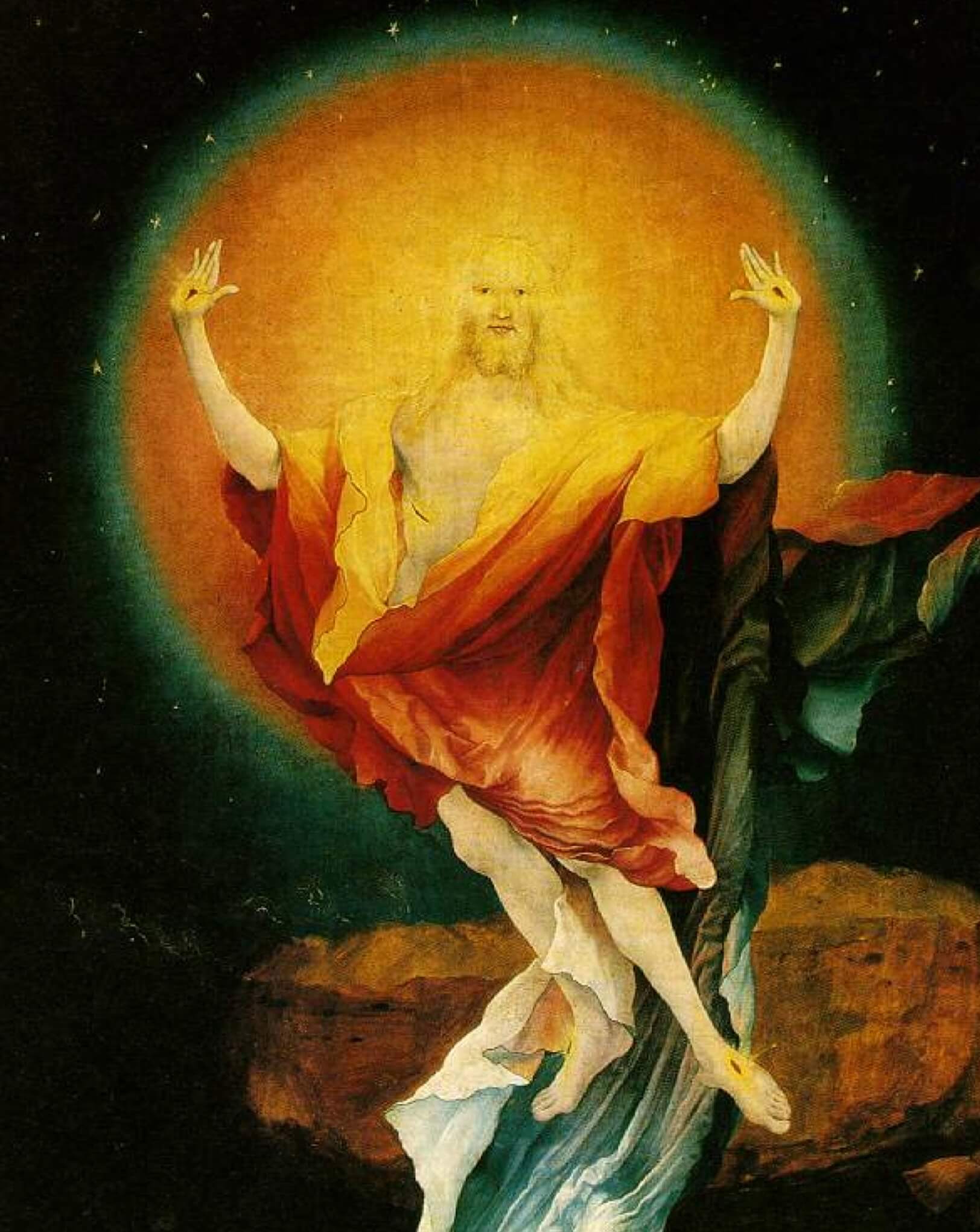

Given its themes of resurrection, perhaps there's no better day to do so than on Easter Sunday.

And on that (C Minor) note I wish you all a very Happy Easter!