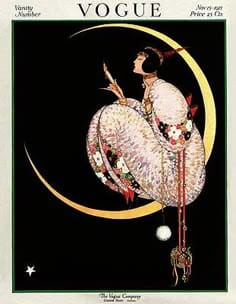

THE MOON AND YOU

Another project of mine that got consigned to the shelf many years ago was a screenplay I wrote with my co-writer, called The Moon and You, which was ostensibly about a Broadway composer/lyricist duo who become embroiled in a love triangle with a childhood love interest. It had a touch of Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in America meets F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise meets Tin Pan Alley, and one of the more subtle, poetic themes underpinning the multi-decade story was the idea of the moon being denigrated as a romantic symbol as soon as it was captured—like a satellite Moby Dick—by NASA’s Apollo 11 crew. Bookended around 1969, at the time of the moon landings, our ageing lyricist, Joe, finds himself alone and bitter, unable to reconcile his Broadway past with his Scrooge-like present, filled with disappointment, betrayal, and a new youth culture that makes no sense to him.

Much of what I believe I brought to the writing table was my deep affection for the work of Rodgers and Hart, famous for their songs of urban sophistication, loneliness, wistful melancholy, and aspirational dreams of romantic love. Lorenz Hart (the lyricist of the team) was forever suffering from acute unrequited love, and his premature death symbolised the end of the old Broadway era, heralding the new one under Rodgers (Hart’s partner) with Oscar Hammerstein, whose post-war Americana optimism gave rise to a new type of musical, most famously Oklahoma!, South Pacific, and The Sound of Music.

Though it was always going to be tricky writing a fictional biopic of sorts, drawing from real-life inspiration of that time, I still think back on the project with great affection for what it attempted to do in its unique, novelistic way. I’m also happy to see Richard Linklater is just about to release his Lorenz Hart biopic, Blue Moon, starring Ethan Hawke, Andrew Scott, and Margaret Qualley, and I have no doubt it will have some flair, even if it lands in that niche “nowhere land” of moderate audience interest.

I do appreciate and applaud Linklater’s mixing of genres from one project to the next, and I will be fascinated to see his new film Nouvelle Vague (about the making of Godard's Breathless), as well as the film version of Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along, a 20-year project in the making (applying the Boyhood approach to having actors age in real time for their parts).

It’s good to know that, even in our brutalised age, there’s still a wisp of romance left in the world of film.