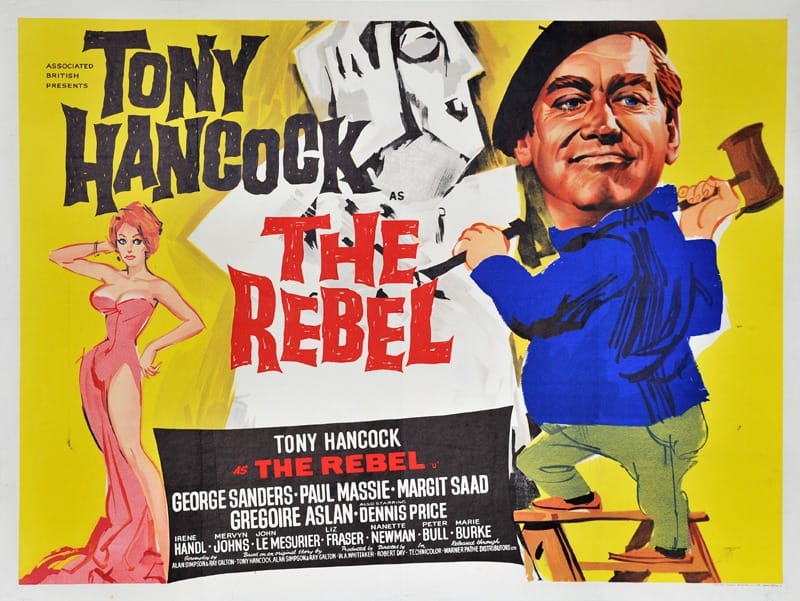

THE REBEL

There are only a few outright comedies I return to often, which include such films as One, Two, Three (1961), The Producers (1967), The Party (1968), and The In-Laws (1979). But right near the top, teetering like a lopsided statue, is Tony Hancock's The Rebel (1961), which has to be the best takedown of modern art and all its pretensions, and demonstrates the British comedian's unique ability to be both childlike and adult-weary all at once.

The synopsis is fairly straightforward. Hancock plays a frustrated office clerk who gives up his job to move to Paris in pursuit of becoming a great artist. Of course, he's terrible at art, and yet, he soon becomes embraced by the bohemian art scene of Paris with his hilariously pretentious art-philosophy waffle at parties hosted by absurd existentialists and who appears to admire his dogged determination to believe that he “has it.” A champion of the “Infantile School” and “Shapist Movement,” Tony ultimately finds his charade undone by his genuinely artistically talented housemate, Paul (Paul Massie).

There are so many gags in this movie, from visual to dialogue-based, that it's hard to pick a few favourites, but a couple that come to mind are one involving Hancock sitting in an English café with continental aspirations asking for a cappuccino with no froth, an unfortunate decapitation of one of his monstrous sculptures in transit from London to Paris, and an action-art painting sequence involving a bicycle, a cow, and a pair of wellies.

There’s also frequent hilarity in the way Hancock’s hangdog face will often break into a huge Cheshire Cat grin before falling back down like a collapsed pair of curtains as he oscillates from joy to despair throughout his own version of An American in Paris — in his case, an Englishman.

Though its critical reception was mixed, with some complaining that it was derivative, the artist Lucian Freud described it as “the best film made about modern art.”

“In 2002, the London Institute of Pataphysics organised an exhibition consisting of recreations of all the artworks seen in the film. There is still dispute over whether the drawings and paintings attributed to Hancock and his roommate were all produced by Alistair Grant (1925–1997), or whether Hancock's poor-quality 'Infantilism School' artworks were actually produced as a joke by the British modernist painter John Bratby.”

What amazes me about The Rebel is how it's largely forgotten as a film, and that it doesn't rank higher on the great comedies list. Maybe I'm biased toward its English-style humour, but I think it has so many great moments throughout that it always surprises on rewatch with its enduring comic appeal.

And, living in a town filled with numerous pretentious artists surrounding me, it's a good reminder to have a laugh at the absurdity of all those who take their work far too seriously.

Tony Hancock's The Rebel is a cautionary tale for all those who try to pretend that they're “artists” when, more often, they resemble frauds — albeit well-intentioned ones.

If I sound jaded, it's perhaps because I've seen one too many “Aphrodites at the Watering Hole” for one lifetime.