THE SEVEN DOORS OF BLUEBEARD

Competing with 'The Red Shoes' as the purest expression of Michael Powell's craft as a director, the recently released and restored 'Bluebeard's Castle' (BFI) truly is a wonder.

Made in 1963, it pre-dates those early years of Cosmotel/Unitel that attempted to advance and make credible the opera film as an art form in itself, which reached its zenith in the late 1970s and 1980s. Some of the more successful examples from that stable included Herbert Von Karajan's 'Das Rheingold (Wagner), Gotz Friedrich's 'Salome' (R Strauss) and 'Falstaff' and Ponnelle's 'Le Nozze Di Figaro'.

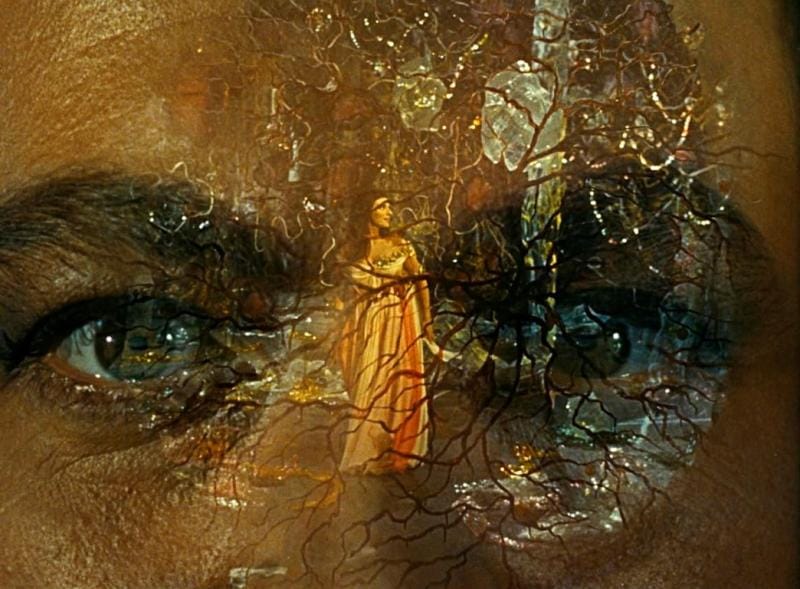

All of these examples are literal, faithful interpretations but lack the elusive mystery that infuses Powell's 'Bluebeard', a West German production made for television which reminded me of that timeless atmosphere of fairytales that I recall from first reading stories such as 'Jorinde and Joringel' and 'Sleeping Beauty' as a young boy. There's a secret place reserved in the child's imagination that exists purely to visualise such things as fairytales - it is that place that J.M Barrie describes so brilliantly, where "if you shut your eyes and are a lucky one, you may see at times a shapeless pool of lovely pale colours suspended in the darkness; then if you squeeze your eyes tighter, the pool begins to take shape, and the colours become so vivid that with another squeeze they must go on fire." Powell accesses this same hidden place of the secret imagination and brings his bold, abstract vision to life on screen, helped undoubtedly by the sinister sets designed and built by Hein Heckroth (famous for his work on stage productions across Europe including the first ever production of 'Don Giovanni' at Glyndebourne in 1936 as well as the iconic sets for Powell & Pressburger's 'The Matter Of Life And Death' (1946) movie.)

The opera itself takes place in the windowless hall of a mysterious, shadowy castle described as being 'like a cave hewn in the heart of solid rock', where seven closed doors remain locked.

Upon the arrival of Judith at his Gothic domain, the duke asks if she, his bride, is happy to stay, providing her with the opportunity to leave should she so desire. Judith agrees to join him in his home but insists on one proviso: that all seven doors inside the castle be opened so that light might enter the gloomy place. At first Bluebeard refuses, stating that these are private rooms not to be explored by anyone but him and asking Judith to love him with no further questions, but Judith persists with her request and eventually prevails over her husband's initial refusal.

As each room is revealed to Judith she sees something different behind each one of the seven doors, including a torture chamber with bleeding walls, storerooms filled with weapons of war and riches (smeared with blood) as well as a secret garden with bloodstained flowers. Opening the fifth door, Judith is met with dazzling sunlight from a window overlooking Bluebeard's domain. He tells her that the realm she sees before her is now all hers but Judith becomes increasingly concerned at the blood-red clouds she sees gathering just beyond the castle. Whilst Bluebeard hopes that his bride will look no further into the rooms, Judith's curiosity remains stubborn and unwavering as she enters the sixth room which is filled with 'a sea of mournful water' (tears) and begins to enquire about the women Bluebeard has previously loved. Suspecting that the seventh door is where the bodies of his past loves are kept, she is more determined than ever to see what has been forbidden to her and kept hidden all this time.

When Judith persuades Bluebeard to let her open the final seventh door, it is with grave sadness he hands over the last key.

Behind the seventh door are the Duke's three former wives, still alive 'in a space between life and death' and dressed in crowns and jewellery. They emerge, silent in procession as Bluebeard, overwhelmed at the sight of them, hails each in turn as his wives of dawn, midday and dusk, finally turning to Judith and proclaiming her as his fourth wife (of the night). Judith is horrified at the title and begs him to stop, but it is too late. He dresses her in the jewellery the others wear, which she finds so heavy it forces her head to bow under the weight. As she follows the other wives along a beam of moonlight back through the seventh door, it closes behind her, leaving Bluebeard all alone in the darkness.

Bartok's opera is sinister and brief. The brevity of the piece is one of its greatest virtues as it completes its story and themes in a single, masterful act. The audience, like Judith, is held in suspense for the duration with no interval to divide the action or allow us to process what exactly is happening to them in this 'hyper-present' music drama, fever dream.

Ian Christie points out in his commentary provided as an extra feature on the Blu-Ray that only Joseph Losey's 1979 film of Mozart's 'Don Giovanni' and Hans Von Syberberg's 1982 of Wagner's 'Parsifal' share a similarly immersive cinematic approach to adapting opera on film.

Powell's framing and visual storytelling certainly handled the transitions of the score/story as brilliantly as you might find in a superior opera house production. The film expertly captures and enhances the existential horror/fairytale atmosphere of Bartok's masterpiece as if suspended in a realm beyond time, that dream/nightmare place where one is only liberated upon waking.