TOP 5 SCORSESE MOVIES OF ALL TIME (RANKED)

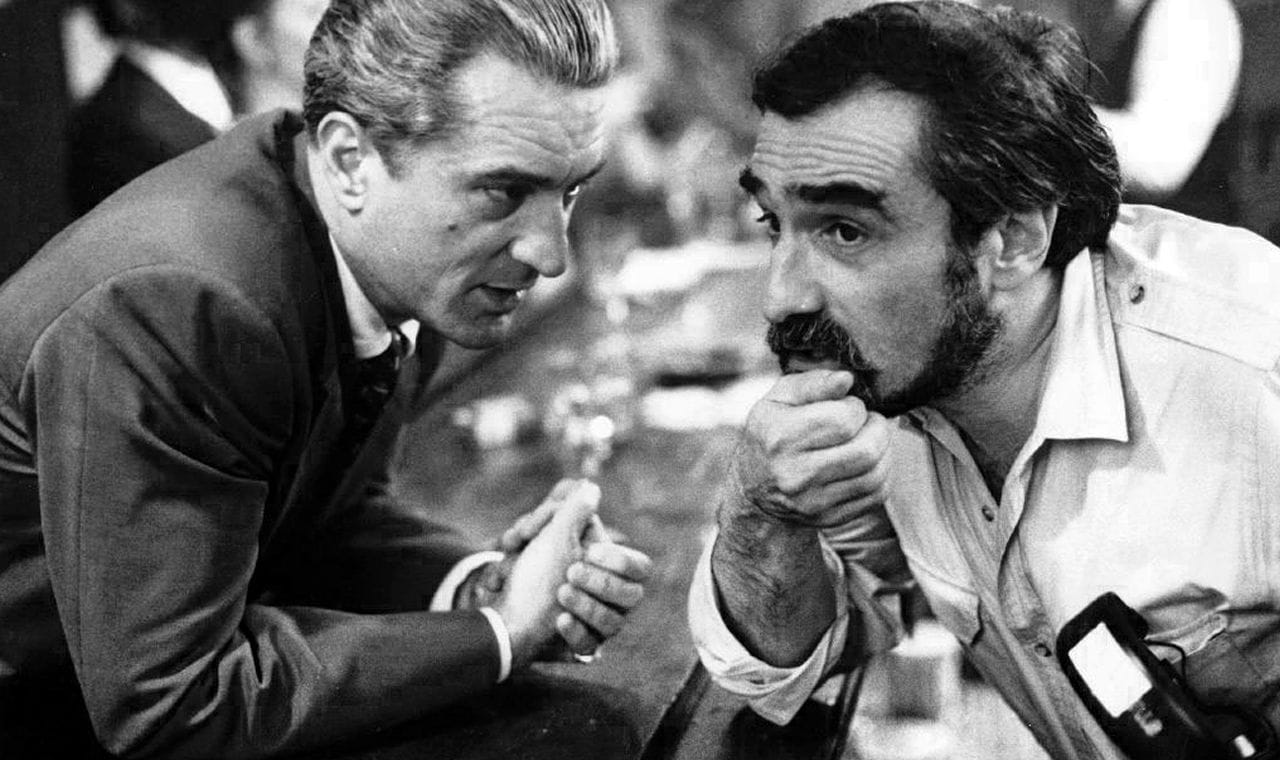

So, after finishing the highly enjoyable and impressively candid five-part series Mr. Scorsese (Apple TV), I’ve decided to attempt a quick top five of the director's best movies, according to my highly contrarian opinion, and see what lands where and why.

Scorsese, unlike directors such as Spielberg, Hitchcock, Lynch, Kurosawa, or Kieslowski, has less of an obvious signature style. At times, he seemed to have been a director in search of a style, but he has always had exceptional stylistic flourishes which have ultimately become his style. The jukebox soundtrack, for example, which he practically invented and made his own, has become much imitated and often suits the way he cuts the scenes and sometimes entire movies (see Mean Streets, Goodfellas, Casino, etc.).

Now, there may be some controversial omissions for some. In the end, I’ve chosen the top five Scorsese films I’d be most likely to return to and continue to get something from.

5. Taxi Driver/After Hours

I guess I'm technically cheating starting this top 5 by choosing two films as one, but somehow Taxi Driver (1975) and After Hours (1985) seem like a perfect double bill, one thematically heavier than the other but both glorious depictions of New York after dark. Where Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) in Taxi Driver is a disturbed loner surveying the modern city with despair and anger from his cab, Griffin Dunne is an office worker who follows a romantic impulse only to find himself trapped in New York's Soho District, becoming further entangled in numerous wild and crazy situations that possess the unique surreal quality of late nights in a crazy city.

Given the controversy around John Hinckley Jr.'s obsession with Taxi Driver, inspiring both his attempt on Ronald Reagan's life and feeding an obsession with actress Jodie Foster, it's impossible to ignore the presence of the film arriving just a few years before the shocking assassination of John Lennon in New York City. The killer, Mark Chapman, in that instance cited Salinger's Catcher in the Rye as his influence. I've often thought Travis Bickle appears to resemble a more adult version of Holden Caulfield from Salinger's most famous novel, albeit not as intelligent as the younger protagonist, but nevertheless both characters out of sync with the world and sharing a similar quality of the outsider in a lonely City, tuned in almost exclusively to the intense thoughts in their heads. And if Holden is protective of his kid sister, Phoebe, then Travis has his equivalent in a strange sort of way with Jodie Foster's teenage prostitute, Iris.

As for Griffin Dunne's office worker in After Hours, he appears to represent the work-beleaguered man looking for something to shake up his 9–5 office world and finds it in the smile of Rosanna Arquette, who starts up a conversation with him in a café about the novels of Henry Miller. She, in turn, is like a midnight muse, leading him to an underworld of insanity where nothing rational occurs, and which he soon wants to escape from, finally desperate to return to the world of conformity where he starts his 9-5 office day all over again.

Taxi Driver’s status as a seminal film of the 70s is well deserved, and it works both as a piece of history about a Vietnam-fatigued America as well as capturing the general despair of that hangover decade that came after the countercultural aspirations of the 60s were blown apart. There's no peace and love left anymore in the country, only in the tacky, heart-shaped sunglasses that Iris wears on a coffee date with Travis. This is the underbelly of the American Dream where, like all the assassins before him in America’s history, Travis looks to change the state of things with the use of violence. The evocative Bernard Herrmann score, which recalls an older New York — one that harks back to old black-and-white films — creates a strange cognitive dissonance with the gritty modern feel of Scorsese's zeitgeist movie, but somehow it makes total sense, bridging one age of filmmaking in the city with another.

After Hours is a significant film for different reasons than Taxi Driver, as it established the working relationship between Scorsese and legendary cinematographer Michael Ballhaus. You can see, even early on in this low-key feature, a new type of cinematic lexicon being developed between them that would feature to an even greater extent in major works such as Goodfellas and Casino.

4. Raging Bull (1980)

Raging Bull is not an easy watch. Jake La Motta is a genuinely loathsome character, and his motives for fighting are not always clear, unlike Rocky or one of those more conventional boxing biopics, but we do sense the longer the film goes on that the fighter enjoys a kind of sado-masochistic relationship with the sport at which he excels. What goes wrong for him in real life can be atoned for in the ring, and this back and forth between his private life and the fights that take place in the squared circle are like a kind of mirror that holds up the true beast inside him that needs to be judged. Of course, sometimes La Motta uses the ring to avenge his demons, and it's only when we see him lose control and commit violence to those he holds closest in his private life that we sense he's lost the balance that brought about his greatest successes as a fighter. Once he's past the point of no return, he can no longer use the ring to address his issues and has to reconcile with all he's lost, including his beautiful wife and loyal brother. The genius of the film is, like Jake, we can never be sure of who has betrayed him and who hasn't. We may not like it, but just as Scorsese and most definitely De Niro identified aspects of their own selves with the boxer, we too must recognise there's a Jake La Motta “Raging Bull” inside all of us.

Of course, the sublime use of Mascagni's intermezzo from his one-act opera Cavalleria Rusticana during the opening credits for Raging Bull is a key reason why I would find it hard not to include the film in a Scorsese top 5 list. Most films that reference opera in serious fashion and not parody get my attention almost instantly.

3. The Color of Money (1986)

The task of creating a sequel twenty-five years after the original pool hall masterpiece The Hustler by Robert Rossen might have seemed daunting to many directors, but Scorsese seems to find some of his most relaxed form in this 80s 'safe space' of hustlers and gamblers where "Fast Eddie" Felson deals with the reality of getting older whilst watching a new version of his younger self in the form of Tom Cruise's Vincent clean up on the pool tables of Chicago, Atlantic City, and New Jersey. Torn between being a mentor or a rival to the kid, Eddie has to make a choice, either accept growing old and packing up the thing that's defined his whole life, or get back behind the cue and knock some balls into some pockets.

Newman's performance is one of the most natural he ever gave and the one film that secured him a Best Actor Oscar. There's a lived-in feel to the way he inhabits the character of Fast Eddie, just as there is a lived-in feel to the way Scorsese makes a movie that is free from the more lofty aspirations of some of his other films. Still, in this freedom of making a 'studio' film, I think he's close to being at his most consummate as a director. I can imagine always trying to be an auteur can be a drag, and it's good to sometime let a project take the lead in a way that isn't always being wrestled from your soul.

Between Scorsese and Ballhaus's partnership and Newman's sublime performance, we also get a cocky young Cruise at his most punchable — perfect casting for a role that's designed to needle the old hustler himself.

2. Goodfellas (1990)

Of course, this could easily and should really be number one, but where's the fun in that? As much as Goodfellas ticks every box for a Scorsese fan, I just can't quite help myself stalling here at the number two spot. But it's kind of criminal, as the film is basically perfect. I think it's safe to say that Scorsese peaked in 1990 with Goodfellas, where all of his life experience and skill as filmmaker and storyteller, drawing upon the genre which has come to most define him, came together in a couple of hours of cinematic perfection. Whether it's the amazing use of voice-over, freeze-frames, tracking shots, or authentic dialogue, there's something for everyone who loves cinema here.

The early scenes that seduce both us and our narrator and chief protagonist, Henry, into the mafia world could easily be the best mafia recruitment video ever, but the longer the film goes on, the heavier the price for this gangster's paradise has to finally be paid. We (and Henry) understand that being part of the mob is not all fur coats and Bobby Darin singing at your table in the club. There's the complete implosion of your private life, the threat of prison, and the blood-stained guilt that eats away at you like a gnawing rat.

Navigating the line between being both seductive and cautionary, Goodfellas is one of the great American movies, which both celebrates the allure of the gangster world but never fails to remind us of its horror.

And of course, it has one of the greatest title sequences, accompanied by the sounds of Tony Bennett's "Rags to Riches."

1. Life Lessons (1989)

Scorsese hits upon something profound in this short 45-minute film based on Dostoyevsky's The Gambler, included as part of the New York Stories triptych of films, which also included a short by Francis Ford Coppola and a short by Woody Allen, both far less successful than Scorsese's miniature masterpiece here.

One reason I love this movie so much is because it gets at the heart of the artist as part genius, part emotionally undeveloped child. Nick Nolte's performance as Lionel Dobie is pitch-perfect, and as he paces around his New York studio/loft apartment like a grizzly bear, splattering paint onto giant-sized canvases all the while listening to Procol Harum or Puccini's Turandot, it's hard not to get the feeling that Scorsese relates to this same duality as a filmmaker. Dobie's need to have a muse to keep him company while he creates art is both selfish and needy and exposes just how locked away he is with his art, hiding behind it like a shield so that he doesn't have to face the truth about who he truly is as a man.

There's an assurance, both visually and narratively, with this economic piece of filmmaking that shows Scorsese as a true master, as well as his expert use of music to capture the essence of his characters and the emotions that drive them. By this stage in his work with Ballhaus, it's obvious that they're ready to make the far more ambitious and legendary Goodfellas.

Still, I think in its small-scale approach, Scorsese proves that he can be both deft and audacious in equal measure. It's unassuming in one way but epitomises the craft of Scorsese at his very best.