TOP 5 SONDHEIM MUSICALS OF ALL TIME (RANKED)

It was recently suggested to me by a friend of mine that by my stating so assuredly in my ranked list articles that my choices are the 'top of all time' I may come across as arrogant and absolutist and alienate those reading the posts. I should just say for anyone thinking I've gone a little 'Dr. Strangelove' in the arrogance of my unequivocal rightness in these matters, that like most of the human race, my mind changes often. What may seem certain today in my mind, maybe less so tomorrow when I often have additional epiphanies and doubts about the works in question. So this illusion of confidence is actually more transient and less fixed than it may first appear.

And just to further illustrate my sudden bout of self-deprecating awareness, I have decided to omit Sondheim's 'Sunday In The Park With George' from my top choices today as I am humble enough to admit I haven't yet fully got to grips with the piece; it is one I've not had the chance to see live in the theatre which I find often unlocks what power the work possesses to be fully and truly appreciated. 'Sunday' is often talked about in the same awestruck way that 'Parsifal' is talked of in Wagner's canon by his devotees, seeing it as somehow far transcending the other operas in his repertoire. I have glimpsed parts of this realisation with 'George' but not so completely that I can yet confidently include it in my ranking list today. I did, however, write a short DR piece entitled 'Finishing The Hat' (01/07/23) which offered a modest analysis on that key song in 'George'.

And so, with that being said, here are my top 5 Sondheim musicals of all time (ranked!)

5. Pacific Overtures

To invert the tropes of Gilbert and Sullivan's orientalism and write from the Japanese point of view both narratively and musically was a bold experiment by Sondheim and perhaps along with 'Sunday In The Park With George' his second most semi-avant-garde in its way. He himself called it “the most bizarre and unusual musical ever to be seen in a commercial setting" and it's hard to disagree.

The optics of the piece would certainly confuse the minds of those modern, high priest 'woke' accusers of appropriation as Sondheim almost seems to build his musical and lyrical language without any trace of his Western influence easily recognisable, or at least not to my untrained eyes and ears. It's as if he's trying to create a form of compositional and lyrical objectivity in representing Japanese sounds and patterns of language so that he can avoid the pitfalls of colonial stereotypes and I believe he pulls it off with all the immaculate execution of a conceptual, Broadway samurai.

The plot centers around America's 1853 plot to Westernise 19th Century Japan in a pivotal culture clash off the island of Nippon. As the story progresses over the next 127 years, the conflict between the two cultures is represented in the score itself as an unsettling assimilation takes place in stage time whilst we watch the shifting culture play out in front of us.

It's amusing in a way to hear the song 'Pretty Lady' which is two cockney sailors' song of seduction directed at a young geisha and hearing it provides the appropriate sense of awkward, leery entitlement that the scene requires. The prettiness of the melody is sickly sweet in contrast to many of the more Japanese-style percussive and punctuated songs that dominate throughout most of the rest of 'Overtures', often using parallel 4ths and avoiding the pentatonic scale. It's almost as if the seductive Western melody is seen as a deceiving, disingenuous ploy that lacks any sincerity. It is reminiscent in a way of Pinkerton's seduction of Cio Cio San in Puccini's 'Madama Butterfly' but far less grandiose in its statement of tone.

As a re-invention of what music theatre can do when it dares to move beyond its more conventional standard forms, I believe 'Pacific Overtures' is like the freshest sushi garnished with seaweed, flowers and wasabi served up immaculately by Sondheim along with John Weidman and Hugh Wheeler. Cleverly sparing any Western blushes regarding cultural imitation as the problematic cultural vying for dominance, is, in fact, what gives the piece pathos and drives home its subtle yet powerful message.

4. Into The Woods/A Little Night Music

Inverting things, or conversely opening up things previously hidden in woods and guiding them toward the light, seems to be another recurring motif of Sondheim who, in 'Into The Woods', along with his collaborator James Lapine, examines the deeper and more complex issues and themes behind the classic Grimm's fairytales (via Bruno Bettelheim's book 'The Uses Of Enchantment') that many of us grew up with as children.

Themes of abandonment, death, personal responsibility and the random cruelty of existence all feature in what appears like a sophisticated pantomime at first. It's actually about as deep as any of Sondheim's work especially when you consider the fact that the work was being written around the height of the AIDS epidemic in New York where the spectre of death hung heavy over Broadway and the music theatre culture. I myself even contemplated staging a dream production that would take place outdoors in Central Park set at that time in history using the parallels of its possibly disguised AIDS parable in a Gilliam-style 'Fisher King' type of production.

Songs such as 'No One Is Alone', 'No More' and 'Children Will Listen' are among the most beautiful and profound of all of Sondheim's work and can be understood as well outside of the show as inside of it. And on that point, what a marvel it is for these melodies and lyrics to have such a profound dual function where they can be both completely integral to the scenes and plot of the shows they're framed within but also become personal anthems for our own human lives. That is the true genius of universality in art and Sondheim never fails in this most important and essential department.

No better example of Sondheim's sublime universality is there than the song linked below 'No One Is Alone' which I've written about previously in 'No One Is Alone' (06/01/22) and again in 'Once Upon A Time' (11/09/22).

With 'A Little Night Music', Sondheim brilliantly finds a way to bring Ingmar Bergman's 'Smiles Of A Summer Night' (1955) to the stage with the wittiest of lyrics and the most gossamer-like of musical scores, creating a perfect adaptation and one that demonstrates the composer/lyricist's increasing sophistication in how he overlays multiple characters singing all at once as well as delving ever deeper into his almost Shakespearian painting box of human emotion. Songs such as 'Every Day A Little Death', 'Send In The Clowns' and 'The Glamorous Life' are clearly evolving the art form considerably from where Sondheim first began with his lyrics for Bernstein's 'West Side Story' back in 1957.

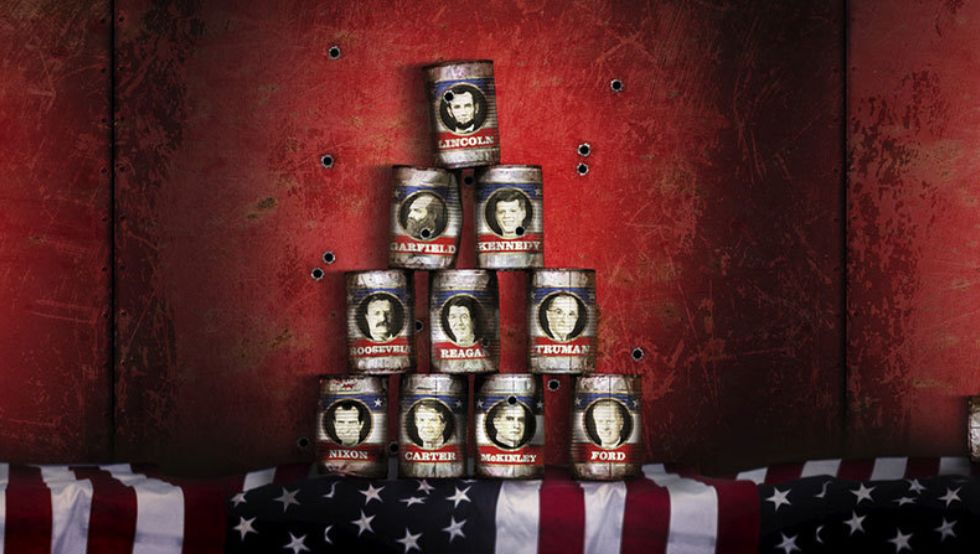

3. Assassins

In these especially febrile times of American political history, 'Assassins' seems increasingly relevant, and although it's actually only been around since 1991, parts of it feel as old as Abraham Lincoln.

This probably has something to do with the ingenious way that Sondheim matches the time period of each assassin with the musical idiom of their day. Whether it be John Wilkes Booth singing a folk ballad 'The Ballad Of Booth' typical at the time of his shooting of Lincoln or the creepy 1970's style maudlin pop duet of 'Worthy Of Your Love' sung by John Hinkley and Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme to the subjects of their 'unworthy love' - Jodie Foster and Charles Manson.

The idea that this collection of murderous outsiders are all somehow unified in an old-fashioned musical revue that marries all the musical styles/genres of each characters era in time to ultimately become like one collective ID that lurks in the shadows at the dark heart of American history is one of Sondheim's most ingenious masterstrokes.

2. Sweeney Todd

Like Mozart's 'Figaro' or Puccini's 'La Boheme', Sondheim's 'Sweeney' is a perfect work for the stage and really by any measure should be number one on this list. You can return to this Grand Guignol music comedy-drama time and time again and never be bored. It is a genuine theatrical marvel where melodies 'drip' like 'precious rubies' as the demon barber famously sings to his shaving instruments in 'My Friends' with glistening lyrics just as razor sharp.

As a statement about the brutalisation of humans in Britain's rapidly dehumanising industrial revolution of the 18th Century, Sweeney is a revenge fantasy that makes Tarantino's recent cinematic efforts look positively tame by comparison.

What makes this Sondheim masterpiece so ingenious is that we, the audience, root for a murderous psychopath as his vengeance seems wholly justified to us in many ways. I've often thought of it as a darker, blood-soaked 'Count Of Monte Cristo' if Dantès never found any money beneath the Chateau D'If and decided to open up a pie/barber shop instead. Both men exact revenge on their enemies except that for Sweeney there is no redemptive happy ending like the Count, just more death and sorrow.

The desperation of people fighting against the upper echelons of privileged society, desperate to even the score is evident in those scenes shared between Sweeney and Mrs Lovett which are both comic, rousing and chilling all at once.

What greater testament to 'Sweeney's brilliance can there be that something so dark in theme can be so addictively moreish? It's almost as if Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler conceived the whole show as one piping hot pie that smells delicious until you look closer at the grisly contents inside it.

But by then it's too late. You've already bitten into it.

The two contrasting scenes below show that thin line between comic darkness and tragic darkness throughout the show and how quickly they can flip from one to the other. In the first video, Mrs Lovett (Imelda Staunton) is selling Sweeney (Michael Ball) on her idea of turning humans into pies to which they begin to riff together in comical fashion on the business proposition.

In 'Epiphany' - the second clip, Sweeney has been triggered by the fact that he's just let his enemy and subject of his vengeance, Judge Turpin' slip away before he had a chance to kill him. Here we see the full extent of Sweeney's wrath as we now know there will be much worse to come in the show yet.

1. Merrily We Roll Along

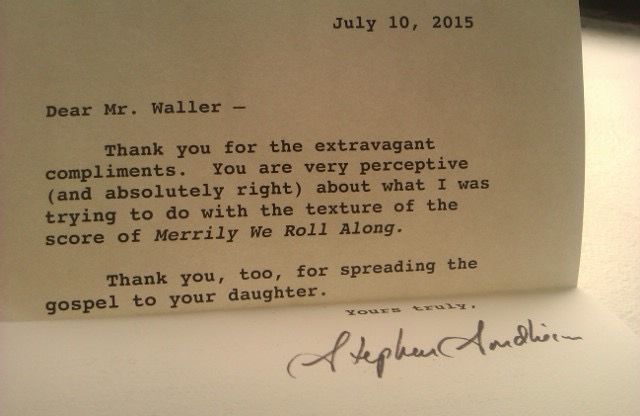

'Merrily We Roll Along' may be the most obviously flawed of my top 5 but perhaps the most emotionally satisfying with the caveat that 'George' may one day usurp it. I remember the first time watching it and realising that Sondheim had pulled off the most incredible theatrical magic trick which was to reverse the structure of the characters' lives so that we start at the ending and end at the beginning in a similar way to Harold Pinter's 'Betrayal'. Musically, the effect is deceptively profound as the texture of the musical score becomes lighter while the psychological and emotional subtext gets heavier, a point I raised with Sondheim personally and was lucky enough to get his agreement about the point.

Perhaps having worked in the creative arts to some degree myself, I found myself easily relating to the three central characters of 'Merrily', Frank, Charlie and Mary and the ups and downs they suffer through their respective careers. Holding onto your dreams without being battered into complete submission by the tempests of life, can be a common challenge for all of us and the sinking feeling that you've lost something you once held close to your heart because life got in the way has been rarely better conveyed than in 'Merrily' which one reviewer described brilliantly as like being "poisoned by champagne".

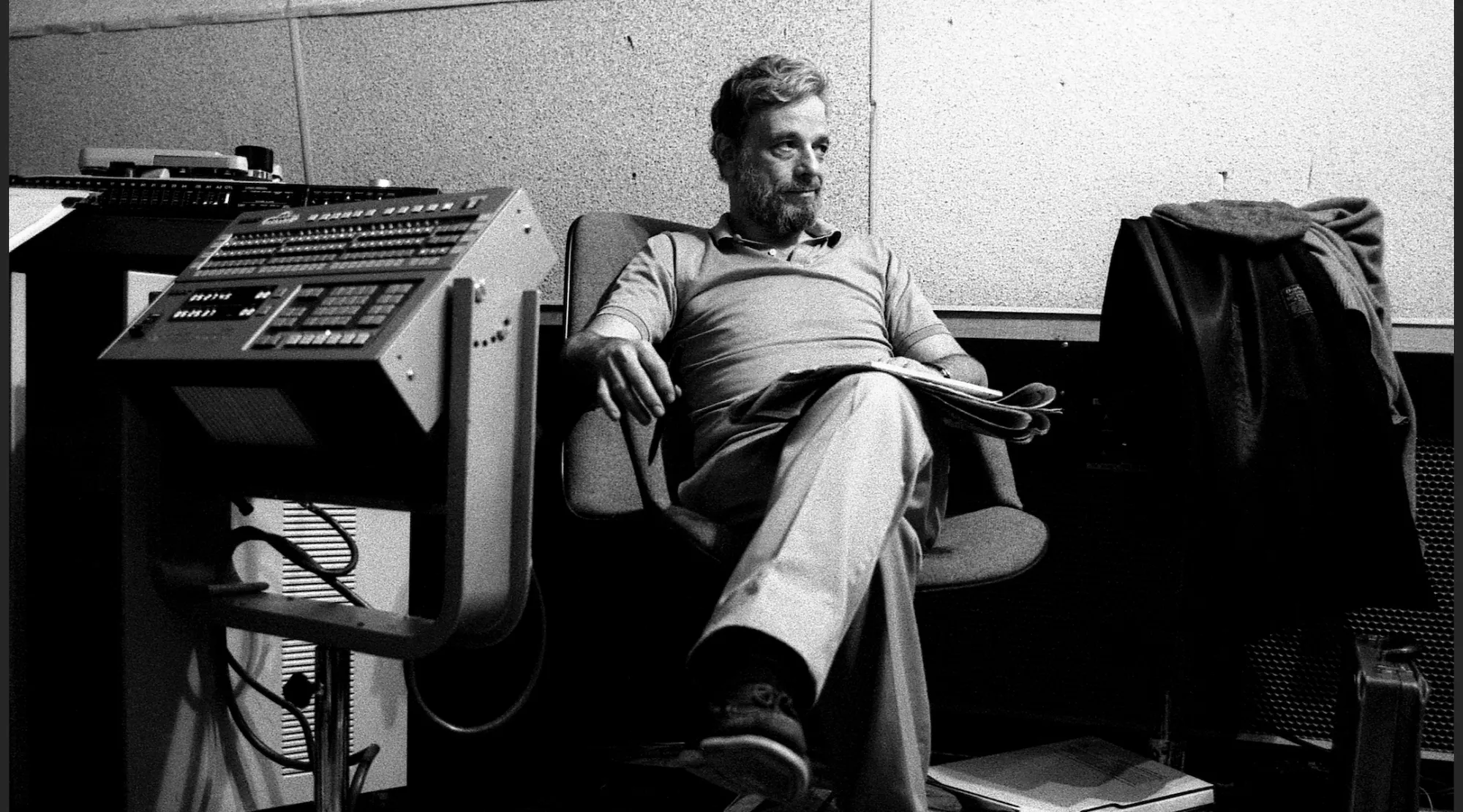

In conclusion, there is no feasible way to summarise the rich feasts of each of Sondheim's works as they, like the greatest operas, require a lifetime of exploration. But if I were to compare these theatrical monuments to another famous artist then it might just be Stanley Kubrick with his films, as he, much like Sondheim, always seemed to look to reinvent with each of his projects and attempt to change and impose a new perception of the genres he took his hand to.

Perhaps the most moving aspect of Sondheim's immaculate career and timeless legacy is that he was passed the baton of musical theatre by his mentor, Oscar Hammerstein, who became a creative father when he was 10 years old and offered the young Stephen an escape route from his almost psychopathically unfeeling mother.

What's even more remarkable is that Sondheim never let the toxicity of that damaged relationship affect the humanity and compassion of his work. A lesson for all of us, I believe.

In the two clips shared below, we see two stages of Frank and Charley's creative relationship; one at the tail end and one at the beginning. Similar to the contrasting scenes of Sweeney above, here we see how the comic becomes semi-tragic and how the pathos is greater when we have traveled back through time with them knowing it ends badly for their dreams of youth much later down the line.