HONOURING THE PAST

Watching Powell and Pressburger's 'Black Narcissus' (1947) last Saturday afternoon in Avening's Memorial Hall introduced by the director Michael Powell's widow and three time Oscar award winning editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, I had a profound sense of cinematic and historical continuity as I looked upon the ceiling struts high above framed like praying hands. I thought of that incredible duelling preparation scene in his 'The Life And Death Of Colonel Blimp' (1943), an audacious visual tease which famously dissolves to the carriage outside in the snow before we can bear witness to the ensuing action.

As it turned out, the memorial hall also happened to be the exact same venue in which Thelma and Michael Powell held their wedding reception almost forty years ago which seemed notably poignant. And although there were technical issues with the screening of the film itself, the goodwill for the occasion overrode the glitches and brought with it a sense of profound gratitude for two main reasons: firstly, that Powell had been saved from obscurity in Avening by New York director, Martin Scorsese in the mid-1970s and secondly, that Thelma, Michael Powell's widow, continues to honour his legacy, not only by talking so lovingly about her late husband's films but also through her own incredible work in film editing of which she is undoubtedly one of the great masters of the last fifty years.

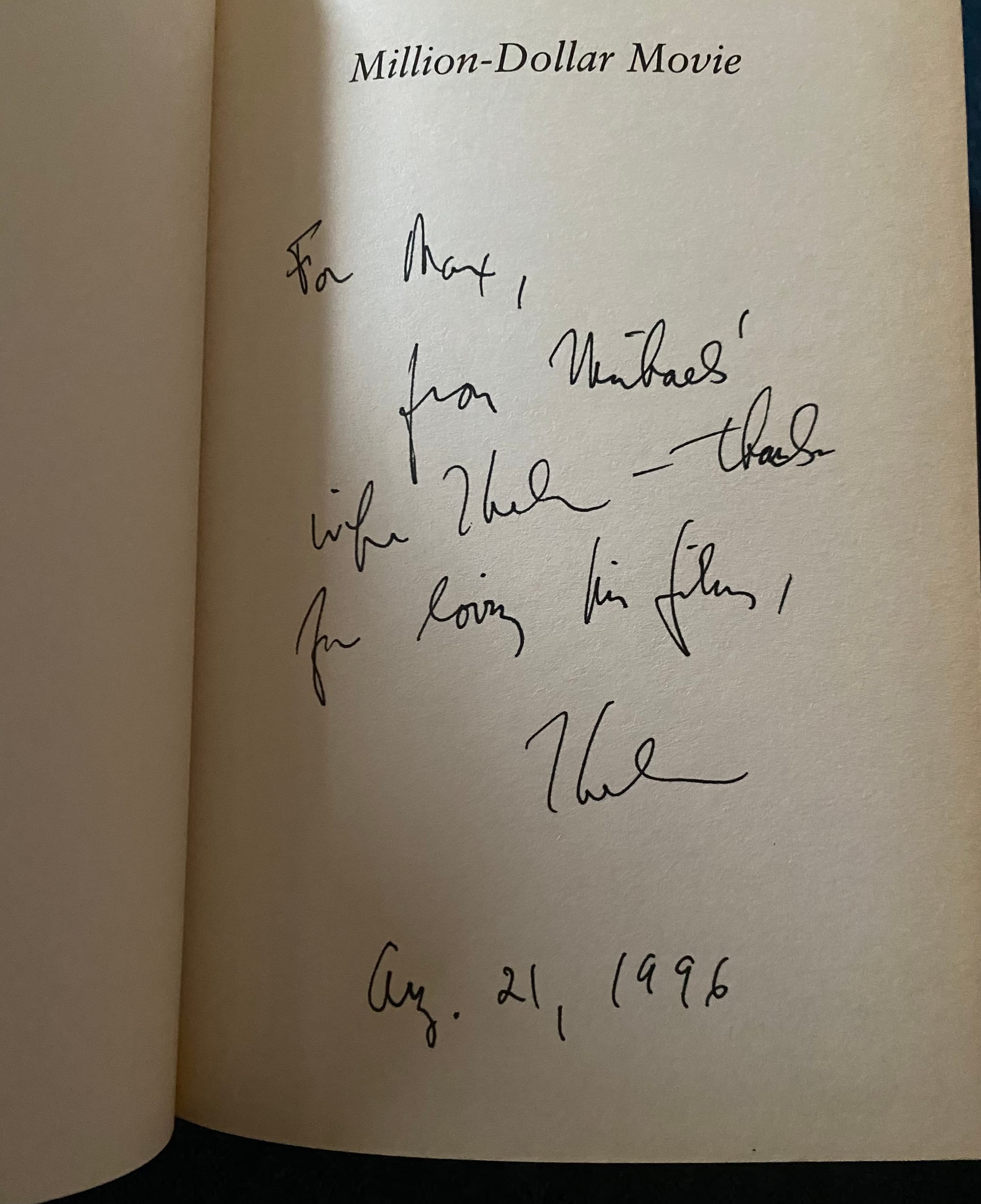

There is something humbling about seeing a woman of 83 years of age still at the cutting (pun intended) edge of her profession and with such an obvious passion for film. It certainly eliminates any excuse-making for one's own lack of productivity to be in such prolific and prestigious company. I found myself becoming all too aware of all the decades that had passed in my own life since I first met Thelma in person back when when I was a teenager in 1996.

In the film 'Black Narcissus', Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) has left her old life in the west behind, having joined a convent stationed in the east to pursue a religious life and forget a doomed romance with the man who broke her heart. The exotic, mountainous environment of the Himalayas initially seems as far away from Sister Clodagh's past as it could possibly be and yet through hallucinatory memories induced through the atmosphere of the place, she couldn't in fact be any closer to it as she realises with crystal clarity what it was exactly she has been running away from. This is made even more overtly evident when Clodagh discovers Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron) after she has swapped her nun's habit for more feminine garments and make up, and finds a reflection of her own former self in the antagonist.

Seeing Thelma Schoonmaker after many decades made me think how in many ways I was now in the opposite predicament to Sister Clodagh, having stayed in much the same place for most of my life. And yet, I too was being reminded of the past and all those youthful dreams of film that took me on many Quixotic attempts at climbing my own Himalayas, if not literally then metaphorically.

As a marker of time, it was both profound and sobering. What had I really achieved in the intervening years and what sacrifices had I made that justified the journey I had been on? When Michael Powell found himself like a creative stowaway in Avening after being ostracised by the film industry for making the controversial film 'Peeping Tom' (1960), I wondered what doubts might have preyed on his mind at that time. According to Thelma he was greatly aware that he had had a good run and that he would always far rather have achieved greatness with his work and walked the path less travelled than just become another mediocre filmmaker who bowed to interfering producers.

I must have been twelve years old the first time I heard the name Michael Powell after entering a flower shop at the top of my local High Street, where the woman (aptly named Rose) behind the counter said "You'll never believe who just called?" I had no idea.

"Robert DeNiro!"

The famous actor had apparently called the florists directly to order some flowers for the funeral of the great British director in 1990. His unconventional headstone in Avening's 'Holy Cross Church' remains one of the most unique I've seen to this day and is movingly inscribed with the words : 'film director and optimist'.

Cut to six years later and a carpenter friend of my father's who had been working on the cottage belonging to Michael Powell, had got talking to his widow about the local teenager who was obsessed with cinema. Subsequently, the carpenter drove me over to Avening one evening where I spent many hours talking with Thelma and her step son, Columba. Of course, my awareness of Powell and Pressburger's movies had greatly improved since entering the flower shop and I had already read volume one of Michael Powell's autobiography. I had also absorbed the films of Scorsese (thanks to my cineaste friend, Gorodish). 'Mean Streets', 'Taxi Driver', 'Raging Bull' and 'Goodfellas' had all become staples of my film watching pursuits. Conversing with the editor of these films which were informing so much of my increasing understanding of the cinematic art form, was a truly magical 'pinch me' moment. Then, holding the actual letter from Gene Kelly written to Michael Powell after watching 'The Red Shoes' for the first time, felt like touching a most precious artefact of history in my young hands (further enhanced by my obsession with MGM musicals at the time). I left that evening with the proverbial wind in my sails and a sense I was headed in the right direction with my passion for film.

Now, decades later, I have felt more like screenwriter, Joe Gillis in Billy Wilder's 'Sunset Boulevard' (1950) beat up, disillusioned and uncertain about his future writing for the movies as he plans to leave Hollywood and return to Dayton, Ohio just before stumbling upon Norma Desmond's 'White Elephant' mansion in the hills of Bel-Air. However, watching 'Black Narcissus' and admiring Schoonmaker's never fading passion for cinema has reminded me of that great, long-held dream all over again. Finding the glowing embers of that dream in the same place where Powell had found himself marooned from the film business seems ironic, but as Sister Clodagh discovers in 'Black Narcissus', sometimes your past refuses to forget about you. Scorsese rescued Powell from destitution and welcomed him back into the world of film where he could resolve the issues of his past in several new chapters (including marrying his wife, Thelma) as well as finally getting the recognition for his masterpieces that he truly deserved, including the unfairly maligned 'Peeping Tom'.

The combined magic of Powell, Pressburger and Schoonmaker continues to inspire and revive this tired spirit of mine after all these years and somehow, I find myself much like Colonel Blimp who promises his late wife, Barbara, that he will 'never change' until their house is flooded and becomes a lake. Observing a solitary leaf floating on the water where an emergency cistern has been deployed in the bombed out ruins of his house, Blimp defiantly exclaims ; 'Here is the lake and I still haven't changed".

I still haven't changed either.