WILD AT HEART AND WEIRD ON TOP

“We are like the spider. We weave our life & move along it. We are like the dreamer who dreams & then lives in the dream.” - David Lynch

Great artists have the ability to invade not just your reality but also your dreams. Ever since my teenage years, David Lynch has burrowed deep into my imagination and subconscious, much like that sinister frog-bug creature that crawls into the mouth of the young girl in Episode 8 of Twin Peaks: The Return (2017). A cinematic dreamcatcher, Lynch has inspired both beautiful dreams and terrible nightmares in equal measure for generations, proving himself to be a natural successor to Edward Hopper, Norman Rockwell, and Edgar Allan Poe in depicting the light and dark of both America and the American psyche. He was also a sort of successor to Alfred Hitchcock, sharing a voyeuristic ability to observe his characters' fears on screen and explore what they reveal about the dark corners of human nature. Blue Velvet always felt to me like an X-rated fusion of Rear Window and Shadow of a Doubt, while Mulholland Drive seemed like a modern-day Vertigo. Perhaps it's no coincidence that Lynch was often described as "Jimmy Stewart From Mars," a nod to one of Hitchcock’s favourite actors and an icon of American cinema with homespun appeal, which Hitchcock loved to subvert.

Back when Twin Peaks dominated the excited conversations at my secondary school, little did we grasp just how much David Lynch was redefining and subverting the American soap opera before our eyes (and ears) in a way that would forever change television and popular culture. All I knew then was that something impercetible was shifting in how I looked at reality itself. With Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) as a protagonist who used dream logic to investigate the mysterious murder of prom queen Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee), I realised that my own peculiar way of intuiting things wasn’t quite so odd after all. Dale Cooper’s dream-led approach to enquiry was an extension of Lynch’s own creative process, rooted in his practice of dream meditation. The director later articulated this approach in his part-autobiography, part-self-help guide, Catching the Big Fish, and through the work of his David Lynch Foundation. It certainly explains his unique ability to reach the minds and hearts of his audience in strange and mysterious ways that set him apart from his cinematic peers.

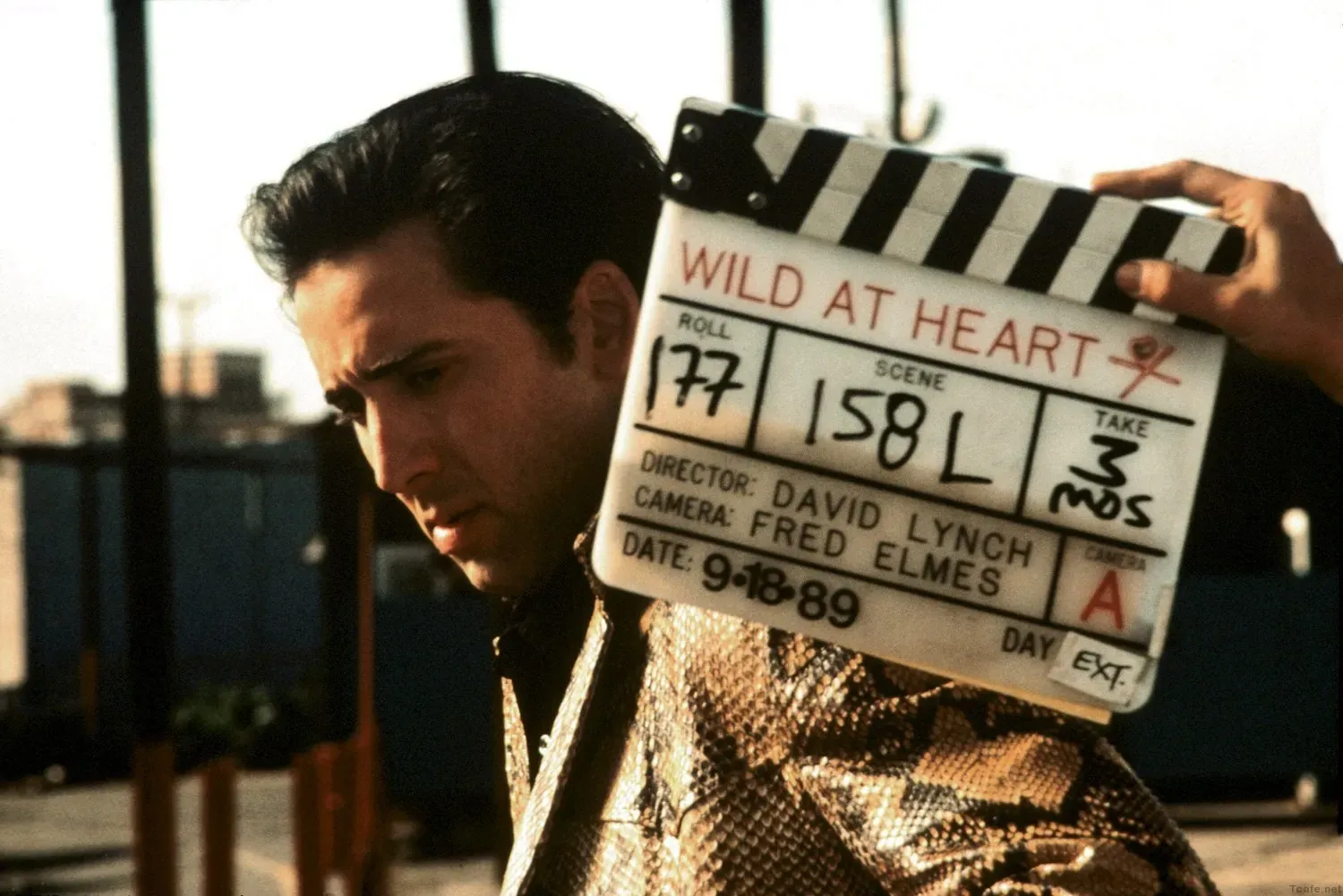

During those teenage years, when Twin Peaks was sweeping all before it in terms of cultural influence, my love of black coffee, doughnuts, and women who resembled the female stars of Old Hollywood became a major preoccupation. So too did my love for Lynch’s films, especially Blue Velvet and Wild at Heart, which carried a forbidden quality that made them feel like the coolest movies a young cineaste could access. It was impossible not to relate to Jeffrey Beaumont in Blue Velvet as he became entangled in the dark underworld of the seemingly wholesome small town of Lumberton, or to aspire to Sailor Ripley’s dangerously passionate spirit in Wild at Heart as he sang Elvis songs and karate-kicked his anger into the dust. Lynch captured the full spectrum of human emotion in a way that transcended artifice, creating something both vital and ethereal that resonated with the cosmos itself—like Walt Whitman’s barbaric yawp and Julee Cruise’s siren song.

Hearing of his death a few hours ago, I found it impossible to simply shrug off the news, even though recent reports of his failing health had made it seem inevitable. Lynch was a titan of American art, his work bordering on the supernatural in its impact. The idea that his dream—and ours—could ever end feels antithetical to his philosophy. I imagine he would see death as merely a cut from one scene to the next in the continuous dream film of unbroken totality where nothing is ever truly lost.

And I’m pretty sure Agent Cooper would agree with that.

David Lynch - 20 January 1946- 16 January 2025