X IS FOR XENNIAL

"The Gen Xer fears the power level of the Xennial." - Anon

Perhaps it’s apt that George Lucas’s Star Wars came out the same year as the birth of the micro-generation known as the Xennials—who, according to Good Magazine, "serve as a bridge between the disaffection of Gen X and the blithe optimism of Millennials."

I never really subscribed to the concept of belonging (in a Pete Townshend kind of way) to a generation—that is, until I started recognising certain characteristics of Gen Xers in articles I’d read, which I mostly related to and identified with.

So, after (sort of) connecting to a generational tribe, I began to quite like the idea. But now, having read up on Xennials (and discovering that I am one), I’m starting to truly feel like one of the chosen people for these chaotic times—a cross between a Jedi Knight, a Goonie, and Ferris Bueller, perfectly balanced between the pre- and post-internet eras.

Forged in the fire of technological "progress," yet hardwired with just enough sentimentality for the analogue world that existed before digital, we are hybrid creatures—part hobbits of the Shire, part Blade Runner/T-800.

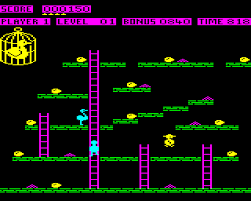

With real human memories of an analogue childhood unblemished by social media, the closest we came to computer engagement was playing Chuckie Egg in IT classes on clunky BBC Micro computers. How compelling it was to run around as Hen-House Harry, collecting eggs and dashing up and down purple neon ladders to avoid hens—a more agricultural version of Pac-Man.

There was certainly no fear we might mistake the crudely rendered Chuckie Egg for reality—unlike so many simulations today, which offer vast Ready Player One universes to disappear into, if disenchanted with our real lives.

And yet, although we Xennials have one foot in the analogue past, we’ve adapted (mostly) effortlessly to the complexities of the digital age—with a surer sense of identity than fluid Millennials or zombie Zoomers. I’m reminded of Haley Joel Osment’s robot-boy character in Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg’s Artificial Intelligence, the last generation of machines manufactured by humans, carrying a faint trace of sentience in his emotional design.

There was certainly a sense—at least before the events of 9/11 ushered in the dread of the 21st century with the explosions of the Twin Towers—that we had lived in a near-perfect peacetime world throughout most of our childhood and teenage years, with little awareness that the implosion of the West was about to begin.

In some ways, I liken Xennials to Luke Skywalker before his Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru were killed by Imperial stormtroopers on Tatooine, leaving him (along with the Rebel Alliance) to figure out how to save the galaxy under the tutelage of Obi-Wan Kenobi—who, of course, also dies not long after (though not in the ultimate sense).

Perhaps it’s ironic that the actor who played the Xennial poster hero, Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), has himself become something of a real-life Darth Vader—or even a Palpatine—seemingly deformed by a kind of Baby Boomer liberal outrage and intolerance toward anyone who doesn’t share his exact One World/Death Star philosophy. In many ways, his performance in 2017's The Last Jedi felt like a reflection of the rot that had taken hold within his soul, teaching many of us who grew up with him as our hero that even the good can turn bad. Or mad.

Yet the archetype of Luke Skywalker remains, regardless of the increasingly erratic Mark Hamill, and we Xennials carry our Jedi sensibilities into a fragmented world of collective psychosis and delusion—still hoping that one day we might defeat the Evil Empire (which we once believed to be fiction) and find our way home safely.

Even if that home now exists only in the mind. ^^